Man beats death with help from UMC trauma team

The injury he suffered to his aorta causes death 98 percent of the time.

He also lost an eye, punctured a lung, chipped a vertebra, and broke nine ribs and seven shoulder bones.

That 52-year-old George Lawes, a Wells Fargo Bank manager, lived to tell about a horrific dirt bike accident, which had one doctor believing he was a goner, smacks of Hollywood.

But Lawes' journey from almost certain death on Thanksgiving weekend to heading back to work this week is a true-life tale of emergency medicine at its best.

How he survived will be shared today by doctors, nurses and Lawes' family at the annual University Medical Center Trauma and Burn Survivors celebration - where one incredible story after another will buttress this fact from the National Trauma Data Bank: Of those who arrive alive at Nevada's only Level 1 trauma center, where many have less than a 1 percent chance to live, 96 percent survive and are discharged.

This year the event, which gives trauma teams and patients and their families a chance to meet again under far better circumstances, is being held at 11:30 a.m. at Caesars Palace's Empress Court restaurant.

"Without UMC, I'm dead and I could never enjoy my family again," an emotional Lawes said Sunday as he kissed his 1-year-old granddaughter, Sophia, in his Summerlin home. "They will always be what is most important to me."

While riding a powerful Kawasaki dirt bike during a November family outing near the Paiute Indian Reservation north of Las Vegas, Lawes, a former motocross racer, lost control at 90 mph. According to the Las Vegas police report, Lawes fell after he "hit a slope on a dirt road" and then was dragged for about 174 feet before the bike landed on top of him.

His son-in-law, Jeremiah Williams, headed to where he saw dust billowing in the desert. He found Lawes unconscious, with his helmet twisted halfway around his face and his goggles pulled down. His breathing was labored.

Williams, a Ford diesel mechanic, said his adrenaline kicked in, allowing him to throw the 250-pound bike off Lawes.

Lawes' fanny pack, which contained his cellphone, was thrown into the bushes. Williams and his wife, Christina, managed to find it. She dialed 911 and began to pray for her father.

"We were so lucky that we found it right away," she said. "It was the only cellphone we had with us. Without it, we would have had to drive for miles, and Dad would have never made it."

It was the first of several developments that had to go just right for Lawes to survive.

Within a quarter of an hour, paramedics arrived. After inserting a breathing tube into Lawes and determining that his injuries would never allow him to survive the long ride to UMC, the paramedics called an air ambulance. Minutes later Lawes was flying to the trauma center.

Less than 45 minutes had passed since the accident, and Lawes' body was being scanned for injuries under the direction of Dr. Michael Casey, the quarterback of the trauma team.

The good news was that Lawes didn't suffer brain or major spine trauma. Casey wasn't particularly concerned about the broken bones. They weren't life-threatening and could be dealt with later.

What made Lawes' case a huge challenge was the traumatic aortic disruption, or tear, he suffered and his badly damaged right lung.

Because the aorta, the largest artery in the body, branches directly from the heart to the rest of the body, the pressure within it is great, and the blood may be pumped out of a tear very rapidly, often quickly resulting in shock and death.

Ninety-five percent of those with Lawes' condition die at the scene. Half of the remaining 5 percent die en route to the hospital.

Surgery for the condition is associated with a high rate of paraplegia, or paralysis of the lower limbs, because the spinal cord is extremely sensitive to lack of blood supply, and the nerve tissue can be damaged or killed by the interruptions of blood supply during surgery.

Morbidity and mortality rates are among the highest of any cardiovascular procedure.

As it turned out, Casey had to rule out surgery because he would have had to collapse the left lung to get at the aorta. That couldn't be done because Lawes' right lung was damaged, and he would not have had an air supply.

The situation looked so bleak that Dr. Nancy Donahoe, a cardiac surgeon on hand, suggested to Casey that the family be told Lawes wasn't going to make it.

Casey, however, remembered that there were surgeons in town who had successfully handled similar aortic issues with stent grafts, not on an emergency basis but in the course of their cardiovascular practices.

During the procedure, the surgeon places the grafting material in a catheter and inserts it through a small opening in the groin. With the help of an interventional radiologist, the surgeon works the catheter into the correct location in the chest and then pops open the stent material in the artery, sealing the area where the tear is.

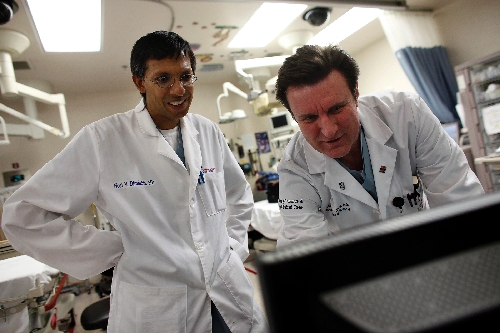

The interventional radiologist on call that day was Dr. Raj Agrawal .

One of the surgeons trained in the cardiovascular procedure locally is 43-year-old Dr. Neel Dhudshia. He wasn't on call on the afternoon of Nov. 27, but he answered the phone call from UMC.

Dhudshia said he would be happy to do the procedure but explained that the special graft material could only be obtained from one vendor in town, Gore Medical's Paul Hasforth, who helps train surgeons in the graft's use.

Dhudshia called Hasforth, who was almost headed out the door for dinner with his wife. Hasforth said he had stent graft material and would drive it to UMC .

"As I was driving, I always expected that I'd be called and told to turn around, that the patient had died," said Hasforth, 65. "Not many of these people hold on for long in a trauma situation."

The fact that Dhudshia and Hasforth rushed to UMC proved to Casey that Las Vegas has special medical professionals.

"I'm so proud that we have the kind of people here that will do all they can to save human life," he said.

Dhudshia thought a higher power might have been at work.

"What are the chances that two people who didn't plan to work would have been home to answer the phone at just the right time on the last day of Thanksgiving Day weekend?" he said. "And what are the chances that the vendor would have just the right size stent graft for this man's chest?"

In nonemergency situations, Casey said, surgeons measure the area that must be fixed so that the right size stent graft can be ordered.

When Hasforth arrived at the hospital, he scrubbed up and went into the operating room with the stent grafts. Dhudshia and Agrawal soon found out he had one they could use.

"Basically what you're doing in this procedure is plumbing," Hasforth said.

The plumbing with the stent graft immediately stopped the leak in Lawes' aorta. An hour after the procedure began, his heart began to pump in normal fashion. Lawes was going to live. In the days ahead, the orthopedic work on his battered shoulder would begin.

Lawes' wife, Lisa, still marvels at how Casey kept her family abreast of what was going on with her husband.

"Whenever he could, he'd show me images, explaining what they were going to do," she said. "I've never seen a doctor work with a family with such compassion. He was actually teaching me medicine. It was the kind of care you always wish you could have."

It is because of that care, she said, that she and her family agreed to have their story told publicly.

"We didn't want any notoriety for ourselves, but we did want UMC to get the credit it deserves," she said. "It is a jewel that we should treasure in this community. They give the kind of emergency care you couldn't get anywhere else in Southern Nevada."

Too often, Lisa Lawes said, people assume that because UMC is a county hospital that serves the needy, the quality of care can't be top-notch.

"I admit our family never thought we would go there," she said. "But now that we have, we see that it has such an advantage being associated with the University of Nevada School of Medicine. At a teaching hospital, they're always working to do it the right way."

George Lawes, who spent two months in UMC and rehab hospitals, still isn't 100 percent. He may never be. He's a regular at the Matt Smith Physical Therapy location in Summerlin, where therapists, including Smith himself, work with Lawes to ensure he has movement again in his shoulder, where his arm basically was torn out of the socket.

It's still not determined whether he will regain vision in his right eye . His vision was saved in his left eye because his helmet covered that eye.

"I'm not complaining - I had so many wonderful people working to keeping me alive," Lawes said.

He agrees with the sentiments of Caesars Entertainment executive Gary Selesner, who worked with UMC to put on today's celebration for survivors.

"All the superstars in Las Vegas aren't glittering on our city's showroom marquees," Selesner said. "Many super-stars save lives round the clock, every day in UMC's Trauma and Burn Center."