Oncologist says ‘magic bullet’ slows progress of breast cancer

In her 40 years as an oncology nurse, Sharon Fuller came to know well what it meant when a woman was diagnosed with stage-4 breast cancer.

She wouldn't be long for this world.

"Many of those patients were gone within a year," the 69-year-old retired nurse said recently as she sat in a Comprehensive Cancer Center office in Henderson. "Death came pretty quick. I remember telling them that it was important to get their affairs in order as soon as possible."

Fuller took her own advice three years ago when she was diagnosed with stage-4 breast cancer. She headed to a lawyer to make sure her will was in order. Checked on funeral arrangements. Talked to family.

The nurse who retired to Las Vegas from New York in 2003 obviously knew the score - she was on death's doorstep.

Her cancer had already metastasized, or spread, to her lymph nodes and liver. Doctors said there was no point in undergoing surgery or radiation.

But then Dr. Mary Ann Allison of Comprehensive Cancer Center added something new to Fuller's life-and-death equation.

She gave her a chance to be part of a clinical trial involving about 130 women that was studying the efficacy of a drug known as T-DM1, a medication designed to delay the worsening of breast cancer without some of the side effects of traditional treatments.

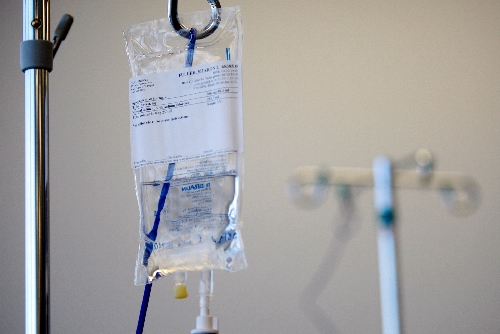

"Of course, I said sure - what other choice did I have?" Fuller said as a nurse hooked her up to an IV line that would dispense the drug in her left arm. "It's the reason I'm alive today. It's a kind of chemotherapy treatment that is making cancer a chronic disease, something somebody can live with, like heart disease."

Allison, an oncologist, calls the drug "a magic bullet. ... It's putting off progression of the disease ... it's adding time for a patient. ... Anyone who has metastatic disease is going to succumb - this is not a cure - but if we can keep pushing the end out, keep pushing it out, you never know what else they're going to come up with to save lives. There's just so much on the cutting edge right now."

When the results of another clinical trial involving the drug were released earlier this month in Chicago - there were 991 women with metastatic breast cancer in the international study - researchers found that the drug not only delayed worsening of the cancer, it also appeared to substantially prolong lives.

An ecstatic Allison said, "Many, many women are going to benefit from this drug." What oncologists had long envisioned was coming true, she said, cancer treatment was killing the cancer and not hurting the patient.

"I really haven't had side effects from it," Fuller said. "And scans show I've gotten rid of seven cancerous nodules, including one in my liver. I've got two left that have grown smaller."

Allison expects the drug to win FDA approval for wide use either late this year or early next year.

"Sharon has a great quality of life and that's obviously what we want," she said. "She's able to go see her sister on the East Coast, basically do whatever she likes."

Donna Katz, a research nurse overseeing Fuller's treatment, said scientists "expect the trial that Sharon is involved in to have similar results to those released in Chicago. Every indication is that the results of her study are very promising."

Results from Fuller's trial should be released in the next few months, Katz said.

T-DMI, and several other drugs in development, are different from traditional cancer fighters because they consist of powerful poisons linked to proteins called antibodies, which latch onto cancer cells and deliver the poison directly into those cells. Because the poison is not active until it reaches the tumor, side effects are reduced.

All of the women in research involving T-DMI - there are 17 studies under way - are HER2-positive, meaning that their breast cancer tumors have a high level of a protein called HER2. About 20 percent of breast cancer cases are of this type, and T-DM1 is designed to treat only this kind, Allison said.

The highly publicized international trial, which started in 2008 and ended last December, compared women who received T-DM1 with women who received Tykerb, also known as lapatinib, and Xeloda, also known as capecitbane. Nearly 85 percent of patients getting T-DM1 were alive after one year, compared with 77 percent of those in the control group. Although the median survival of those getting T-DM1 is not yet known, researchers now believe it will be at least a year longer than the 23.3 month median survival for the women in the control group.

Fuller's trial compares women receiving T-DM1 with a standard of care treatment, Herceptin and a chemotherapy drug called a taxane.

In Fuller's randomized trial, she received Herceptin and a taxane for about a year before her cancer started worsening. On that medication, her hair fell out and she had trouble with appetite and taste. She also felt "wiped out" for a few days after each regimen of chemotherapy.

Switched to T-DM1, she said her appetite improved, she had no problem enjoying the tastes of food, and she didn't lose her hair. After about 18 months on the drug, she continues to improve.

"It's made me a believer," Fuller said.

At about the same time she was diagnosed with breast cancer, Fuller's younger sister was also diagnosed with breast cancer. And her brother was diagnosed with kidney cancer. Other relatives have also had cancer.

"We obviously have a family history but doctors haven't found a genetic link," she said.

Fuller's brother has since died.

Although Fuller's drug trial formally ended a few months ago, she is allowed to stay on the drug as long as it is helpful.

Every three weeks, she receives chemotherapy that takes about 90 minutes.

Now that the trial is over, she has scans for cancer every four months, instead of every few weeks.

Like many people, when she was first diagnosed with cancer, she wondered whether she could receive cutting-edge medical treatment for her disease in Southern Nevada.

"I thought about going back to New York initially," she said. "But then I did some research on Dr. Allison and on Comprehensive Cancer Centers' affiliation with UCLA's cancer research center. It turned out that the latest trials were being done right here. Dr. Allison makes sure of that. It's important that people do their own research."

Critical to the most successful outcome possible in her fight against cancer, she said, is a positive attitude.

"I have some bad days when I worry about dying, I'm not saying I don't," she said as she sat in a room where many people were receiving chemo for a variety of cancers. "But I want to enjoy the life I have. I live now with a friend I knew in nursing school years ago and I get to help with her grandchildren. And I enjoy going to casinos and traveling. I saw too many patients that I cared for just give up and die, who wouldn't give their treatments a chance to work. I can't do that.

"I'm just grateful I have gotten this extra time. I feel great right now. I know there will be a time when the drugs are no longer working and then I'll say, 'God, I'm ready.' I pray that I can handle the end with grace."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at

pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.