Smiling impossible for Las Vegas boy, but surgery may help

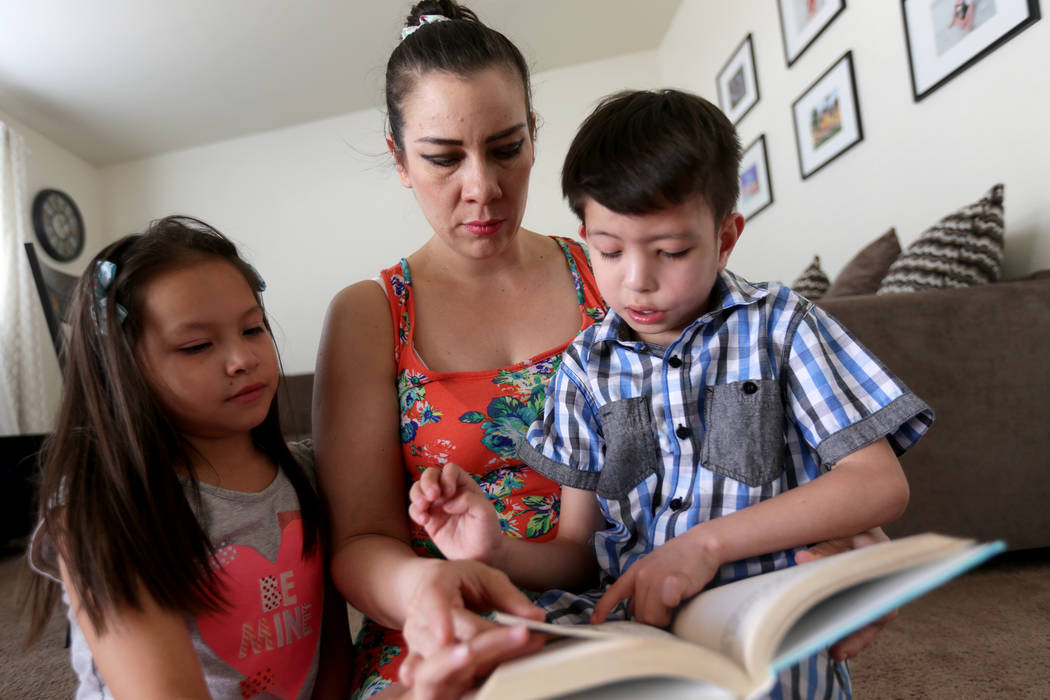

Liz Magana recalls times she saw her young son, without him noticing her, standing in front of a mirror in their home. He’d use his left forefinger, then his right, to try to lift the drooping left corner of his mouth into a smile.

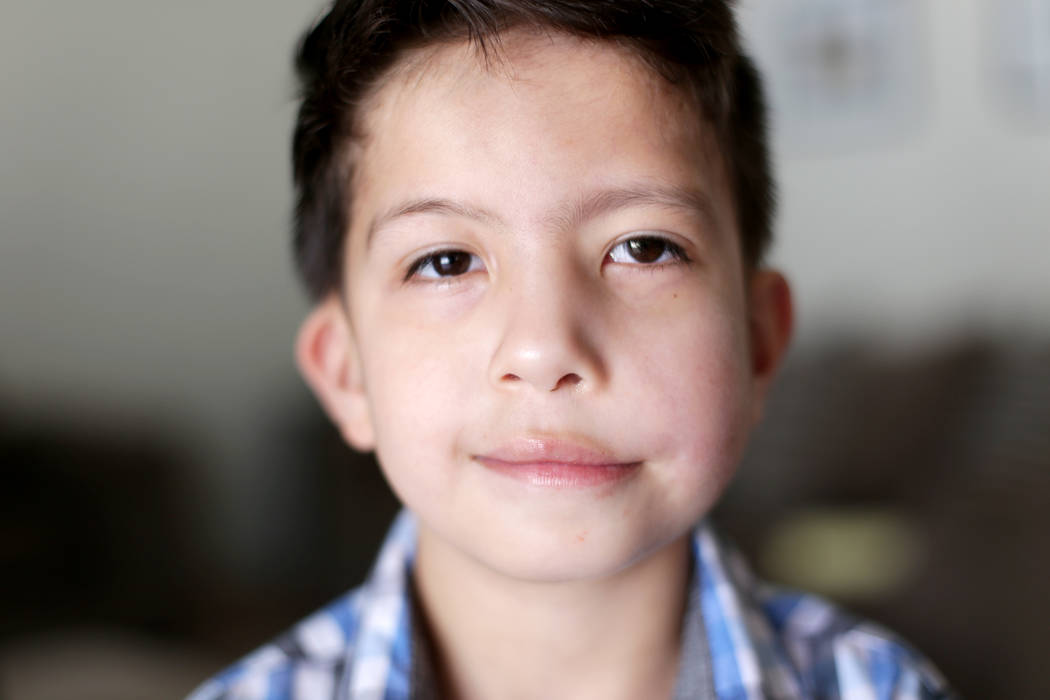

Yet no matter what he did, the paralysis on the left side of his face wouldn’t afford him the look he had on his right.

Magana fought back tears whenever it happened, and would quietly retreat farther into the house.

“I felt so bad for him but didn’t want him to see me crying,” she said.

Her son, who shares a formal name with his father, Abraham Chavez, is known as AB. The young man, now 8 years old, has Moebius syndrome, a rare congenital condition that can paralyze the entire face and affect muscles that control back-and-forth eye movement. His condition is not full blown, and he and his family are hopeful that surgery done in January will eventually let him enjoy a big wide smile.

As Magana talked in the lobby of the Palms — the mother of three works there as a dealer — she sifted through more than seven years of photographs of the AB (pronounced just like the first two letters of the alphabet). Many show an unsmiling, seemingly sad AB, standing or sitting next to his smiling twin sister, Aiden.

“Dr. (John) Menezes says if the surgery works, AB can smile in about six months,” Magana said. “All he’s ever wanted to do is smile like other kids.”

Ready for surgery

It was shortly before noon on Jan. 20 as AB, all 4-foot-4 and 38 pounds of him, waited to be wheeled into the operating suite at University Medical Center, where Menezes would perform the surgery he hoped would unlock some of the paralysis caused by Moebius syndrome.

The boy didn’t appear nervous.

“I just want to be able to smile like other kids,” he said.

AB’s father was nervous.

“I hope the surgery works so he isn’t bullied anymore,” Chavez said.

In shorthand terms, what Menezes did in the next nine hours was transplant the expendable, thin gracilis muscle and its associated nerve from the thigh — several other muscles do its same function — to the cheek to help the boy smile.

If that sounds difficult, it is.

The blood vessels and nerves involved are no more than 2 millimeters in size. Stitches are finer than a human hair. Careful dissection of the tissues and microscopic connection of the artery, vein and nerve can take six to eight hours.

To begin, Menezes created a face-lift kind of incision in front of the ear and extended it below the angle of the jaw. Then, much like a face-lift, the skin and fat are lifted from the cheek, creating a pocket to accept the muscle transplant.

Once nerves and blood vessels in AB’s cheek were identified, the gracilis muscle was transferred to the face and secured to the masseter nerve. That nerve controls the chewing muscle.

According to Menezes, biting down is initially required to produce a smile, but later it’s possible to adapt and learn to smile in an almost spontaneous manner.

Well past dinnertime the surgeon came into the waiting room to tell AB’s family that the surgery went well.

“Thank God,” his mother said.

Nicole Cullison, a pediatric intensive care nurses who watched AB carefully after the procedure, said her young patient never complained about pain.

“All he said was, ‘I just want to smile,’ ” she recalled. “That really got to me — that something I take for granted is so important to someone who can’t do it.”

Cullison noted that research shows the way we smile dramatically affects how we’re perceived by others.

“He wanted this done earlier because he knows those who smile are often better liked,” she said. “Kids are so much wiser and more perceptive than we think.”

Path to recovery

One week after his six-day stay at UMC, AB was back in the doctor’s office. His 2-year-old brother, Adrian, had thrown a TV remote at him and hit him on the side of the face where he had the surgery.

“I was so scared,” his mother said.

No harm was done.

“I don’t think I took a breath while I was at the doctor’s office,” Magana said.

Boys, of course, will be boys. Just the other day AB was bouncing around the room as he and Aiden smacked balloons through the house. At least twice, he fell down. Hard.

“He won’t just sit,” an exasperated Magana said.

Striking about one in 100,000 children at birth, Moebius syndrome also can produce hearing loss and bone abnormalities in the hands and feet. Magana thanks God every day her boy doesn’t have the severest form of the syndrome.

Magana had a high-risk pregnancy with her twins born prematurely through Cesarean section at 32 weeks. Though Aiden’s birth was absent problems and she was able to immediately go home, AB, who’d been in breech position, needed cardiovascular surgery a week after his birth to correct a hole in his heart.

He was 3 pounds 8 ounces at birth and had a problem often associated with Moebius syndrome, a cleft palate. The roof of his mouth contained an opening into his nose, making it difficult for him to gain nutrients from a bottle.

Menezes, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon who made the Moebius syndrome diagnosis, did the cleft palate repair on AB when he was 8 months old. Years of therapy have corrected a speech impediment.

As the swelling goes down in his face from the January procedure and healing progresses, AB is careful about one thing — watching his progress toward a smile.

He monitors it with selfies.

He frequently shows his mother that his lip doesn’t curl down as much.

“AB wants to see his first real smile before anybody else,” his mother said.

Contact Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5273. Follow @paulharasim on Twitter.