Southern Nevada food inspectors don’t aim to be enemy

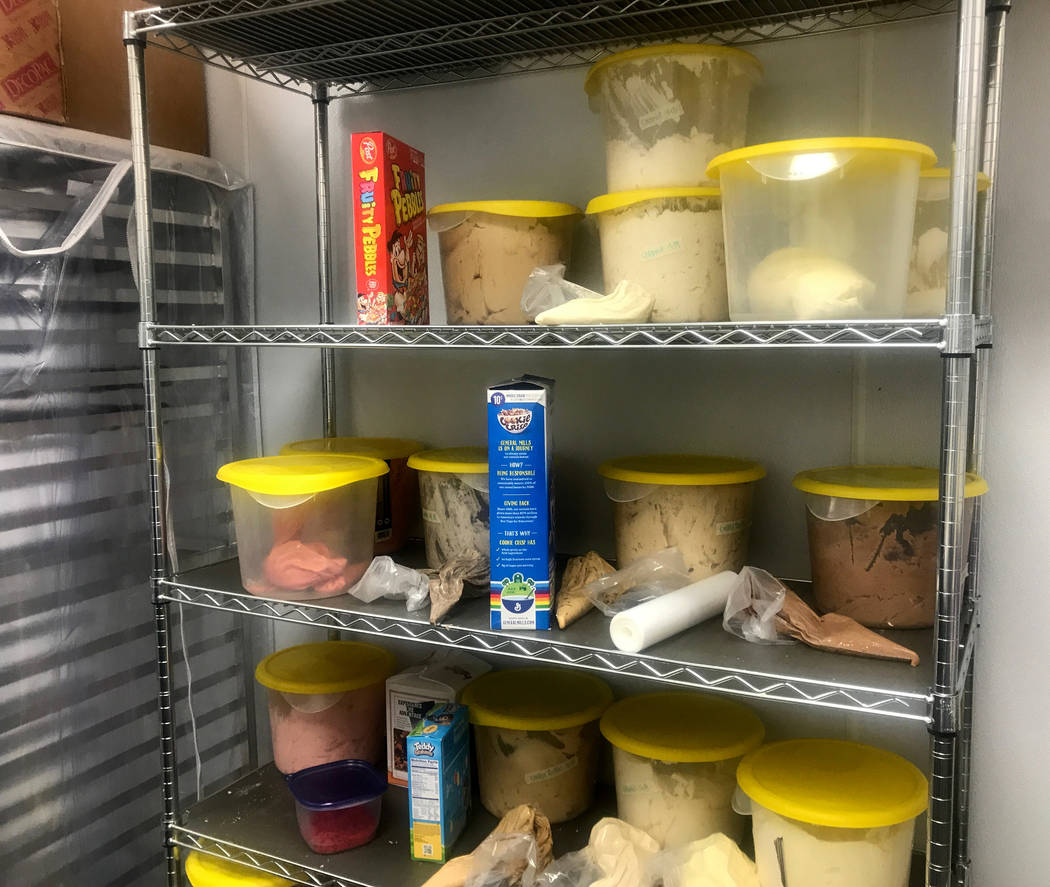

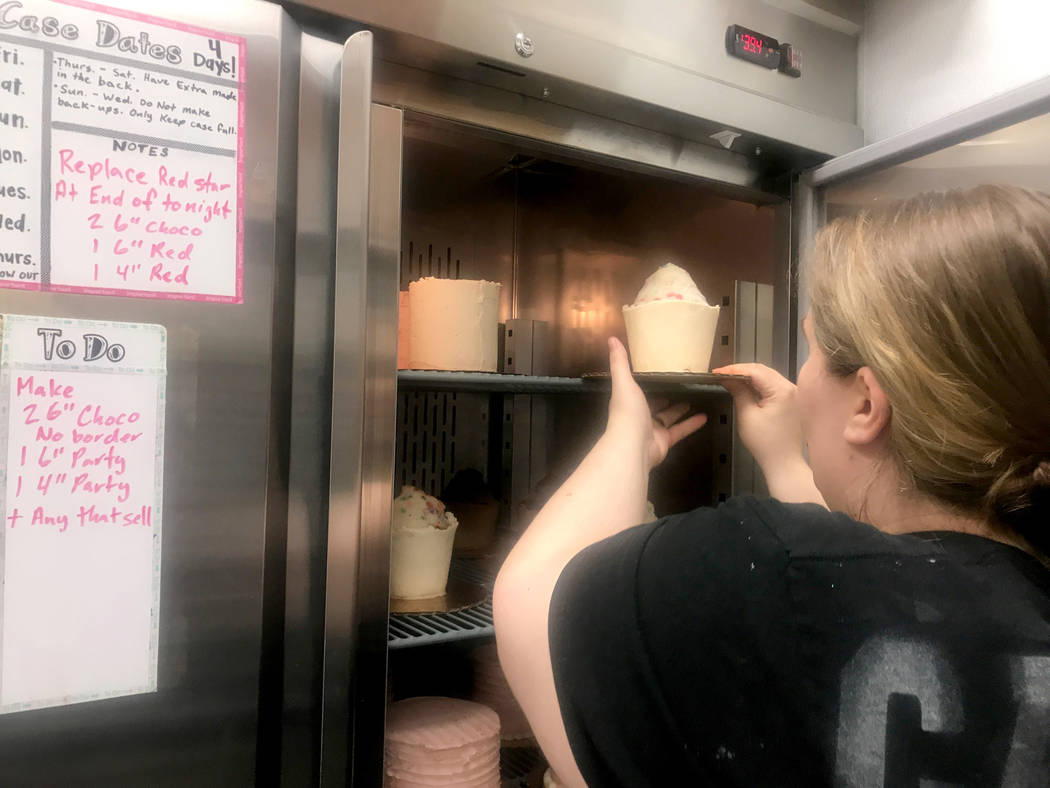

When Kari Garcia was receiving a final review by the Southern Nevada Health District’s Facilities Design Assessment and Permitting department before opening her North Las Vegas bakery in November, the inspector pointed out that she’d missed one minor detail.

The issue was a door that needed the rubber sealing/stopper at the bottom to be closer to the ground to prevent pests from entering and other environmental problems.

Garcia, of Tsp. Baking Co., said she fixed the door by the time the inspector was finished and wasn’t penalized. The FDAP department uses a pass-or-fail grading scale when granting food establishment permits.

“You’re bound to make some mistakes,” Garcia said. “(Inspectors) are not very intimidating if you’re not intimidating. They want for you to be successful, which is a thing that many business owners don’t realize.”

To apply for a permit to serve food, a business operator is required to submit a plan to the FDAP department.

The department reviews construction of the facility, menus, equipment, plumbing, electricity and several other items to ensure they adhere to sanitation standards. There are up to 109 items to review, although not every facility has all of them, FDAP department Environmental Health supervisor Karla Shoup said.

FDAP inspectors conduct an initial design assessment meeting, two preliminary walk-through inspections and one final permitting inspection before releasing permits. Once this is complete, an assigned operational inspector, who deals with food and handling, conducts the grading inspection within 60 to 90 days, Shoup said.

The Health District has nine FDAP and 10 operation inspectors and releases about 250 establishment permits per month in Clark County, including in outlying communities such as Sandy Valley, Logandale and Mesquite, Shoup said. The district has more than 21,000 permitted food establishments; some facilities have multiple permits, said Herbert Sequera, the Environmental Health manager and former supervisor for the operational inspection department in North Las Vegas.

Business operators also encounter the FDAP department if they are remodeling, updating menus or changing equipment, or if they’ve endured a calamity such as a fire, Shoup said.

The most common issue that the FDAP penalizes operators for is inadequate water temperatures, Shoup said. An inspector cannot release a permit unless compartment and hand sinks are at a specific temperature.

Operational inspections are based on a point scale, with 10 demerits or fewer resulting in an A grade, 11 to 20 in a B and 21 to 40 in a C. A business that receives a C grade must pay $477 for reinspection, while those with more than 40 demerits are temporarily shut down. In that case, operational inspectors go back and reinspect the business, said Sequera, who was a supervisor for operational inspections for the since-closed North Las Vegas office for 11 years.

“The misconception of the public is that we walk in and we’re looking into failing them. We’re not doing that,” he said. “Our primary job is to keep the public safe, but working hand in hand, we are educators. We’re regulators and we’re educators because … we can educate the public and the operators to avoid these kind of pitfalls when they go to a facility to eat.”

Businesses receive five-point demerits for critical violations, which are direct issues that lead to health illnesses, and three-point demerits for major violations that are indirect hazards. The most common major violation involves employees not washing their hands for 15 seconds, as required by law. The Health District doesn’t require businesses to have a hand-washing sign for employees in restrooms, but many employers have them for training purposes, Shoup said.

Operating inspectors visit at random — excluding reinspections — usually for 25 minutes to an hour. They visit at least once a year.

“In general, it’s just like a police officer stopping you when you’re driving on the street,” Sequera said. “Very seldom do we meet an operator who shows disconcern to us.”

Garcia said she is anxious when an inspector visits but tries to prepare her staff.

“We try to be as clean as possible anyways,” she said. “I always tell my (employees), think the health inspectors are coming so that way you’re not shocked when she walks in the door.”

Businesses often work with the same inspector year after year. Garcia said establishing a relationship with her inspectors has made her more comfortable.

“A lot of people don’t use (inspectors) as resources. They think of them as the enemy,” she said. “We kind of need to join forces to make sure that everyone is eating cleanly.”

Contact Kailyn Brown at kbrown@viewnews.com or 702-387-5233. Follow @kailynhype on Twitter.

Inspection results

To see how businesses fared in Southern Nevada Health Department food inspections, click here.