Las Vegan continues to fight for Martin Luther King’s dream

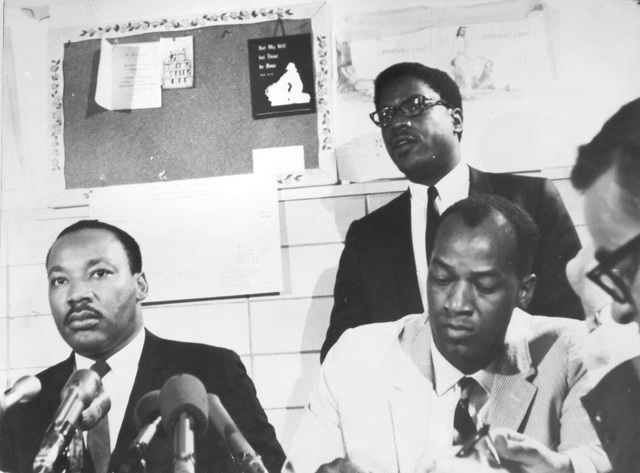

Standing at the right side of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dr. Robert Green never knew one seemingly insignificant moment captured in a black-and- white photo would seal his place in history.

This image shows Green, who had greeted King at the airport in Lansing, Mich., walking and talking with the civil rights leader about an upcoming speech on education.

“I was young and things were happening so fast,” Green recalls. “I never realized the context of what was happening. I never knew we were making history.”

But while the world knows who King is, Green’s story goes largely untold.

Even though the photo shows a time when Green worked side by side with King, Green’s life has been dedicated to advocating for the rights of others, in particular, encouraging educational opportunities. Today, at age 81, he continues in his work.

EARLY YEARS

While his father completed only the fifth grade and his mother finished ninth grade, Green’s parents raised their eight children in Detroit to believe education is the key to anything.

The family knew the bitter taste of segregation and discrimination, but his father often shielded his wife and children from darker events.

“My father had a good friend who was lynched when he was 14 for failing to get out of the way of a white man fast enough,” Green says. “My father had to cut the body down and drag it to the ice house where it sat for two days.”

Green didn’t learn of this traumatic experience until he was 45.

“My father said he didn’t want us to grow up hating white people,” Green says. “My father wanted us to focus on education instead.”

From early on, Green’s life consisted of work, homework and church. Green’s father became a pastor and the family spent several days a week at church.

“Our father would tell us to bring homework to church,” he says. “The only time we were able to miss church was if we were at work.”

After high school, Green attended Wayne State University until he was drafted during the Korean War.

Because he worked as a hospital orderly while attending college, he was sent to San Francisco to serve as a military hospital orderly. Green worked mostly nights in the psychiatric ward on base, which left him free during the day. He decided to use that time to study at San Francisco State University.

On campus, Green became active in civil rights issues, serving as a chapter president of the campus National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

It was during this time Green kept hearing about a civil rights leader, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who so happened to be coming to San Francisco to speak.

“I had been following him and knew he was a glorious person,” Green says. “I would have never dreamt of meeting him.”

Green showed up late to the speech because of work.

“I caught the last 15 minutes,” he recalls.

Afterward, he forced his way through the crowd to meet King.

“Somehow, I was able to get to him,” he says. “I told him my name was Bob Green and that I loved his work.”

He never imagined their paths would cross again.

By 1958, he had been discharged from the military, had a bachelor’s degree in psychology and was married to his wife, Lettie, a bond that continues to this day. Yearning for more, he finished his master’s degree a year later while interning at a school counseling program in Oakland, Calif.

Discrimination was never far away as he applied for jobs. At first, he let his interviewers know he was African-American, a decision that turned out to be a mistake.

He changed tactics during an interview in San Diego when he appeared without first disclosing his race.

“I had an appointment with the head of the psychology division,” he says. “The secretary took one look at me and I knew she wasn’t expecting me to be black.”

The secretary disappeared and when she returned, the interview had been canceled.

“She said the person who was supposed to interview me had something come up and wasn’t there,” he says. “She said he wouldn’t be back for a couple of days.”

He knew finding a job would be nearly impossible. Not knowing what to do, a friend suggested he look into a doctorate program.

“Me getting my Ph.D. shows how a bad act can still lead to something good,” Green says. “The discrimination I faced was the driving force for me to get my Ph.D. It was the best decision I made other than marrying my wife.”

Green moved back to the Midwest and started at Michigan State University, where he received his doctorate in educational psychology and became a full-time professor. Green also served as the dean of urban development at Michigan State.

LaMarr Thomas, a former student of Green who started at Michigan State in 1966, says his life was forever changed by Green’s mentorship. He came to the school on an academic scholarship.

“Green told me, he told all of us, that we shouldn’t just rely on athletics,” Thomas says. “We should think beyond that.”

Thomas put education first, a decision he hasn’t regretted.

He adds that Green helped shape many of the young black men — self-described black militants — and taught them the value of multiculturalism and instilling King’s dream inside of them.

He also fought for equal treatment of blacks on campus, Thomas recalls.

“He worked to expand the access black students and faculty members had,” he adds.

While fighting for others, Green also had to fight for himself. After finishing his doctorate and accepting a full-time job at the school, he and his wife struggled to find a home. Of the 10 houses he applied for, he was turned down for all of them because of his skin color.

“Here I had a Ph.D. and couldn’t even get a house,” he remembers.

When many of his white friends in the community found out, they rallied behind Green, determined to find him a place to live. He eventually rented a house from one of them.

Along with his work in academia, Green was developing his activism.

WORKING WITH KING

A movement was coming in the 1960s to bring equal rights to people of color.

Former Congressman and UN Ambassador Andrew Young, who was director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at the time and an adviser to King, knew it was only a certain type of person who could truly usher in this change.

“We were all certifiably insane,” Young says. “We knew we were at risk of dying. It didn’t matter, because we knew we had the potential to change the world.”

Young knew Green was just the type of person they needed.

The two met in 1963 when Green was traveling to the South.

“There was an instant camaraderie,” says Green, who has been friends with Young more than 50 years. “We both had a passion for social justice.”

During this time, Green developed a reputation as an activist and as a scholarly expert on education and how race and poverty factored in.

King began focusing on literacy in the South and the need for education reform.

Young suggested King add Green as education director for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“He was intelligent and educated,” Young says. “I knew his credentials.”

King supported Green joining the movement. And in little time, Young persuaded Green to join, too, serving from 1965 to 1967.

Green traveled back and forth from Michigan to Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia to meet with King on educational opportunities for blacks.

His time was also spent organizing demonstrations throughout the South.

Green joined Young and King in Selma, Ala., for brief periods including after Bloody Sunday, a violent event March 7, 1965, in which protesters walking over the Edmund Pettus bridge were viciously attacked by Alabama state troopers.

“I flew in right after,” Green says.

That following Tuesday, Green says he and Young organized a march from a church to a police station, but were sent away.

Most of his time was spent in Mississippi, where Green helped facilitate demonstrations such as the March Against Fear, often named the Meredith March for the activist James Meredith who was shot.

During these times, Green could see how the black community was challenged to confront its fear.

“One of the greatest things King did more than any other civil rights leader was to teach the community how to deal with fear,” Green says. “He believed that until black people could overcome their fear of death and love of money, they will never be free.”

Green faced his own fears on rare occasions.

Once during a march, he was hit by several white protesters — they also yelled that he should be shot. Another time, a man pulled a gun on him during a demonstration.

“He could have just shot me,” he says. “I don’t know why he didn’t.”

It wasn’t until a few years ago that Green discovered how the fear of his death took its toll on his sons.

“My son Vince told me that they used to worry about me not coming home,” Green says, taking slow, deliberate breaths while fighting back tears.

During a pause, the reality of his children’s fear overcomes him.

“They used to think I would be killed,” he says, regathering himself. “I never knew that.”

King faced constant threats of violence.

It was 1965 and Green was in the backseat of a car driving through Mississippi. King rode in the front seat. Pulling over for gasoline, King had his window rolled down with his elbow hanging out of the car.

“The guy who was pumping gas stopped pumping, came up to Dr. King and put a gun to his temple,” Green recalls. “He said, ‘I’m going to kill you.’ Dr. King just looked at him and said, ‘I love you brother.’ ”

The guy put the gun down and continued pumping gasoline. Afterward, the car sped away with several anxious passengers in disbelief about what just happened.

As the civil rights movement continued opening doors and breaking down barriers, Green was aware of the grim reality — so often said by King himself — that somewhere out there, there was a bullet with King’s name on it.

“He never obsessed over it,” he says. “He knew it was a possibility and never let it be a deterrent.”

On an April evening in 1968 as Green stood at his bathroom sink shaving and getting ready for a dinner party, he received his first call that the bullet had found King.

Green canceled his plans and sat by the television waiting to hear of King’s fate. Not long after, Green got the call that King was dead.

Students at Michigan State University flocked to his house wanting to do something.

“I had to remind them of King’s commitment to nonviolence,” he says.

The next day, Green along with other administrators and students held an event to talk about King’s death. Some of his students joined him and his wife at King’s funeral.

After King’s death, the Green family stayed close to the King family. Green says several times they had King’s children for spring breaks and took them on trips.

Though King was gone, the mission remained. Green carried on fighting for educational opportunity for all youths. Since his time with King, Green has served as a consultant for school districts across the country and written and spoken on the achievement gap and race and poverty in correlation to education.

“Poverty isn’t the barrier for learning,” he says. “It is rejection and humiliation which are the real barriers. It is low expectations. It is when you expect a kid to be a failure that he is going to fail.”

About 11 years ago, Green and his wife moved to Las Vegas to be near her family in California. The idea was for Green to finally retire.

Instead, he hasn’t slowed down and has taken on more work. He continues as a consultant for the Clark County School District and serves on the board of the Las Vegas My Brother’s Keeper, an initiative President Barack Obama started in 2014 to help black and brown youths with educational and employment opportunities. Green is also working on a memoir.

“I swear, my wife is going to kill me if I take on more things,” he says jokingly.

LEGACY

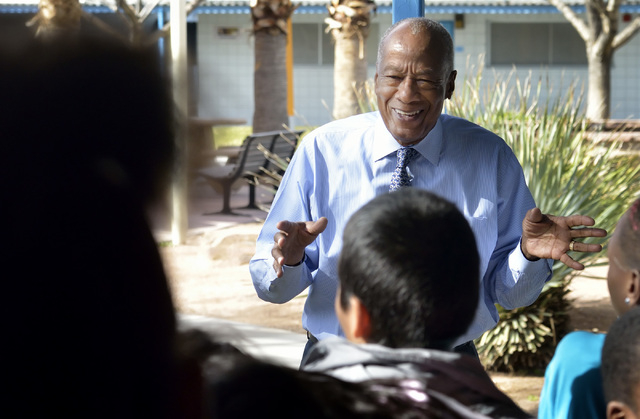

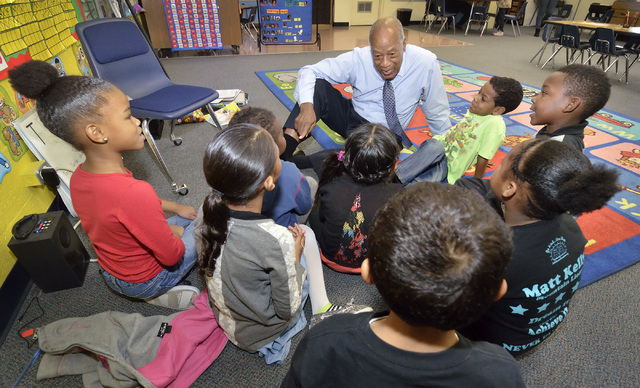

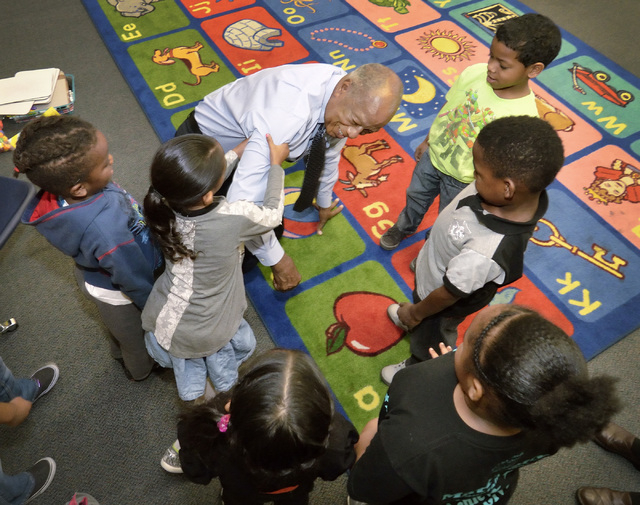

Dressed in suit and tie, Green lowers to the floor to sit among kindergarten students at Kelly Elementary School in North Las Vegas.

“Who knows their ABCs?” he asks, encouraging the children to join in the familiar lphabet song. “Wow, you are all brilliant.”

The students flock to his side answering every question about numbers and letters he throws out at them.

“This is where it starts,” he says. “This is a critical time for them.”

Even though he is supposed to be long retired, Green can’t shake his need to provide educational opportunity for students of any age.

He has met with the school district’s board of trustees and the superintendent on many occasions to discuss the achievement gap or address problems such as the school-to-prison pipeline. Along his journey to lend his expertise, Green says the students of Kelly and Fitzgerald elementary schools have captured his heart.

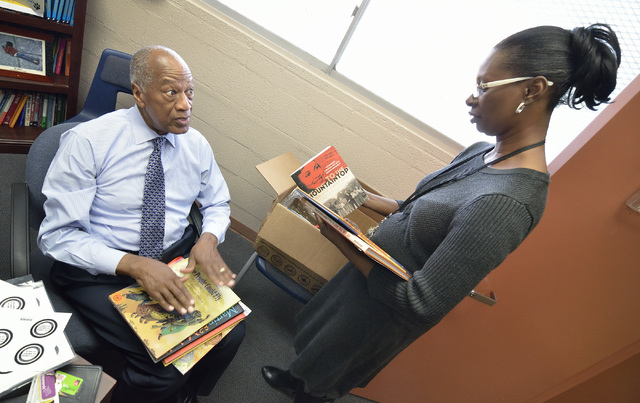

Kelly Elementary principal Lezlie Funchess says Green connected with the administrators at the school to talk about his book, “Expect the Most, Provide the Best.”

“I think having him speak to us is part of our vision to have more community involvement,” he says. “We benefit from his expertise.”

He returns frequently to talk to students about education and encourage teachers.

“I’m here for them both,” Green says.

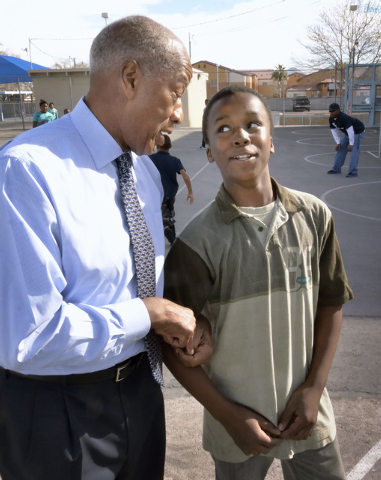

Walking down the hallways, he is greeted by students and teachers excited to see him. Fifth-grader Trayshaun Laushaul runs up to Green to say hello. Trayshaun has his sights set on being an athlete, a cage fighter to be precise.

“I can outrun you,” he says to Green trying to get him to race.

Green has spoken with Trayshaun many times and has the same message he gave to students such as LaMarr Thomas years ago.

“You have tremendous potential,” he says, putting his hand on Trayshaun’s shoulder. “But I want you to excel at reading not just athletics. I want you to excel at science. Once you do that, all colleges around the country will be all over you.”

It is a message he repeats in every classroom he visits.

“How many can read and write well?” he says to a group of fifth-graders who raise their hands. “You have to continue your education.”

Funchess had seen the photo of Green walking with King.

“But I never knew just how involved he was,” he says. “He is a living legend. It is good for students to have examples like him.”

NEVER FORGET

As though he could ever forget his past, the Oscar-nominated movie “Selma” — the film that chronicles the story of King and the people who organized in Alabama to bring about a Voting Rights Act — came out this year, taking Green back 50 years to his work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Green and his wife sat in the theater watching many things he personally fought for take place.

“It did a good job showing what it was like,” he says. “Although, it probably was worse than that.”

It also made him think about all the other places, many of which he visited, that aren’t talked about.

“There are other Selmas that happened,” he adds.

He believes the struggle continues as people are still fighting against police brutality and racially based killings.

“I see it in cases like Trayvon Martin or Michael Brown,” he says.

Also serving as a reminder, the hallway wall leading into his office is covered with photos from his history. Photos of King and Young or images from demonstrations and protests.

On his desk are two signs Green keeps to remind him to never forget where he came from: “Colored must sit in balcony” and “Colored entrance only.”

“I look at these frequently,” he says. “I look at it so my head doesn’t get too big. I look at it to remind me of where I’ve come from. I look at it to remind me that whether it’s poverty in Mississippi Delta or Matt Kelly, there are still things that need to be done.”

Contact reporter Michael Lyle at mlyle@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5201. Follow @mjlyle on Twitter.