CCSD struggles for solutions to special education teacher shortage

Ashlen Atkinson comes from a family of special education teachers.

That’s why it seemed natural for Atkinson, a first-year special education teacher at West Prep Academy in Las Vegas, to pursue the same career.

“As a kid, I enjoyed being the tutor in the classroom,” she said. “I would tutor the other students that might’ve been having difficulties with the material.”

Atkinson, a Las Vegas native and freshly minted college graduate, wants to give back to her community by working with students. She felt particularly pulled to teaching those with special needs.

“I feel like those are the students that are most often neglected,” she said. “I feel like it’s necessary that they have someone working with them that’s passionate about their learning.”

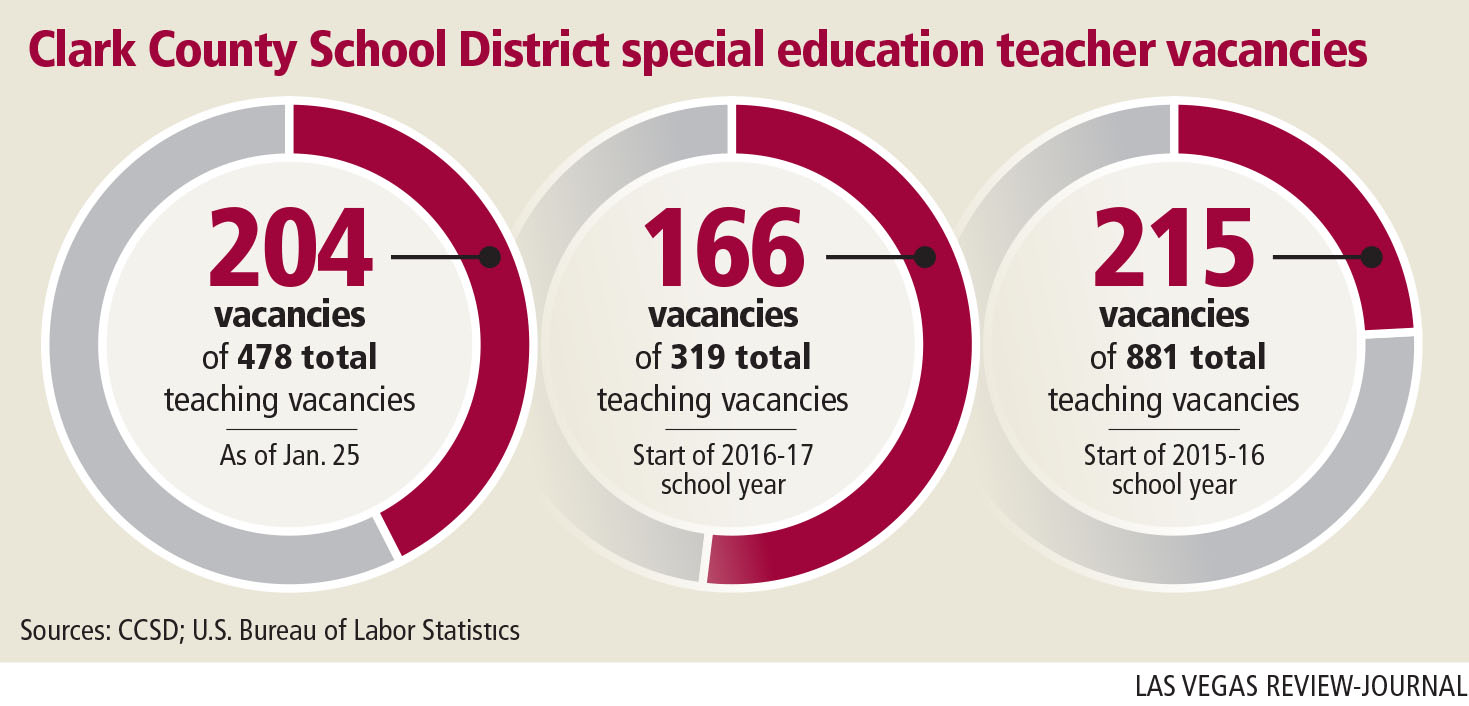

Across the Clark County School District, classrooms desperately need more teachers like Atkinson. Of the roughly 478 teaching vacancies, 204 — or about 43 percent — are special education positions.

It’s part of the continuing shortage that the state faces, but it’s not unique to Nevada. Nationwide, at least 42 states reported a teacher shortage in special education to the U.S. Department of Education this school year.

Those in the special education field have seen the shortage for decades — and are still searching for solutions.

IN RECRUITING, ‘MONEY FLIES’

Jayne Gray said she first got into special education when the government offered to pay back her student loans if she stayed in the field for five years. It was 1972, and her starting salary was $9,500 a year.

Special education teachers have a greater workload, she says, because of individualized education plans, commonly known as IEPs.

The plans are mandated by federal law and cater to each student’s needs. Special education teachers are regarded as captains of that effort, bringing all aspects of one student’s needs into a unique curriculum.

Every year, teachers must craft the plan after meeting with parents, psychologists, speech therapists or other service providers the child needs.

To Gray, who teaches autistic students at West Prep, that means finding time outside the classroom to write plans and organize meetings.

“It is so cumbersome,” said Gray, who has taught in four states over a career of roughly 40 years. “Every district I’ve been (in), there’s no one there to help. It’s just left on you.”

Cynthia McCray, special education director for the district, said the field is particularly difficult because teachers must have additional skills.

“They have to have a deeper knowledge base related to the subject matter,” she said. “They have to know what recommendations that are going into the IEP would be appropriate or not.”

The district uses its own methods to attract teachers, offering certificate and licensing programs to those who are new to the field.

Statewide, other efforts have emerged to attract teachers of all kinds. With Nevada’s Victory School program, for example, teachers can receive up to $3,000 in additional pay for coming to teach at schools like West Prep that have a high-poverty population.

Gov. Brian Sandoval’s proposed budget continues initiatives to attract educators — including $5 million for the Teacher Incentive Fund that will provide up to $5,000 in stipends for newly hired special education teachers. His proposal also includes incentives for teachers in Zoom schools that have high English language learner populations.

Yet after 40 years of teaching, McCray has a few other ideas for districts to fix the shortage — including proper support, mentoring and a higher salary. In Clark County, new college grads start at a base salary of $40,900, although $76,019 is the highest starting rate for a teacher.

“What do they (do to) recruit them? What do they tell them other than, ‘You’ll feel really good about yourself working with kids with disabilities’?” she said. “That doesn’t fly with a lot of people, does it? Money flies.”

TEACHER PIPELINE

As with the general teacher shortage, the issue stems not only from recruiting people — but getting them to stay.

“If people leave, they leave in the first five to seven years of the teaching profession,” said Joseph Morgan, an assistant special education professor at UNLV. “Part of it is really drilling down into why might a person leave the field of special education.”

Another problem is a critical shortage of university professors to train future special education teachers, he said.

In California, Gray said, she saw many people enter the field while they tried to pursue other careers.

“I can’t tell you the number of times I sat down with aspiring actors in L.A. Unified and taught them how to do IEPs and taught them how to do things, because there were no resources telling these people how to be special educators,” she said.

As soon as they landed a part in the movie industry, Gray said, those teachers were gone.

But in Atkinson, there’s a strong conviction to follow the path of her grandmother and cousin, both special education teachers.

She has no hesitation when asked whether she’ll stick around.

“Absolutely,” she said. “This is what I was meant to do with my life.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.