Charter takeover debate in Nevada centers on student scores off new test

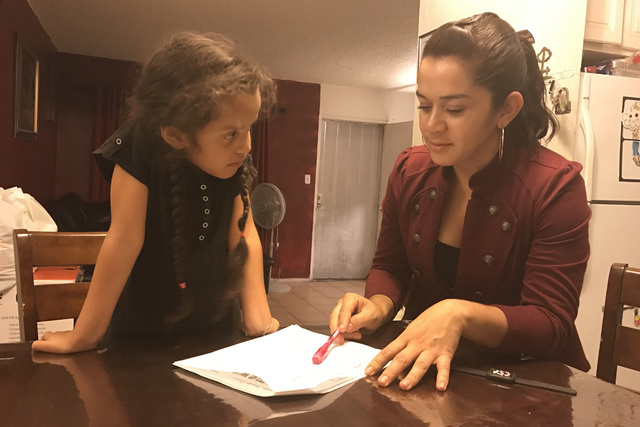

Dalia Jimenez wants her four children to have professional jobs when they grow up.

Jimenez works as a cleaning woman for the local Boys & Girls Club, and isn’t ashamed of it — but she doesn’t want her children to be doing the same.

“I gave life to winners,” she said through a translator. “Not losers.”

But with her downtown Las Vegas ZIP code, three of her kids are in two-star schools, the lowest performance levels in the state’s accountability system. Her daughter’s middle school rates three stars.

Proponents of the Achievement School District say Jimenez’s situation underlines the need for better schools in all areas of the city.

Up to six of the state’s lowest-performing schools will be paired next year with a charter operator and become part of the new achievement district.

The list of eligible schools, now narrowed to nine in the Clark County School District, has sparked a wave of protests throughout the system.

Still, results from the state Department of Education show that proficiency rates from the 2016 Smarter Balanced test at those schools are as low as 7.5 percent in math and 14.2 percent in reading.

The new assessment is considered to be slightly harder than the state’s previous Criterion Referenced Test, and should result in lower scores.

The district, principals and teachers have fought back against the achievement district, arguing that it’s the first time students took the new test.

NO BASIS FOR COMPARISON

They argue that the new scores have nothing to be compared with, and therefore can’t show if student performance has improved.

But even using older testing scores stretching back to 2010-2011, the data show that student growth at these schools needs improvement.

Only 35 percent of students met the average growth percentile — which describes the level of growth needed to become proficient on assessments within three years — in math or reading.

Four of the nine schools have consistently been below 35 percent.

“I think obviously there’s a lot of work to be done with all nine schools — we’re never going to shy away from accountability and showing improvement,” said Chief Student Achievement Officer Mike Barton. “However, I think that there are multiple data sets that need to be looked at.”

There are areas for improvement in growth with the old scores, Barton noted, but schools also need growth data from the new test, too.

“Once the growth data becomes useful with these (Smarter Balanced test scores), it’s another data point to make these schools improve,” he said.

District officials also point to improvements that schools in the district-run “Turnaround Zone” experience.

Turnaround schools saw a 26 percent to 42 percent increase in reading and writing proficiency rates last school year. Math rates also increased from 41 percent to 62 percent, according to the district.

Officials have also pointed to a 2015 study on the Achievement School District initiative in Tennessee.

That study, conducted by Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, found that Memphis’ iZone schools — similar to Clark County’s turnaround program — showed more improvement than those in the achievement district.

Clark County schools face another challenge — a high number of English Language Learners who might not do well on a test in an entirely new language.

Yet the explanations still do not settle the question: When and how will these schools get better?

DIVIDED STAR SYSTEM

Jimenez went from working full-time to part-time because of concerns over her oldest son, who attends Desert Pines High School.

It was one of the 21 underperforming schools eligible for charter-school conversion, but didn’t make the final cut this year.

Jimenez said she hears about many fights there, and although her son isn’t caught up in them, she wants to keep a closer watch on him.

Though her son is applying to a magnet school, she’s not going to run away from the issue by finding other schools for her three daughters.

“That would be a way of ignoring the problem, saying, ‘I’m just going to pluck my kids out and put them elsewhere,’” she said. “And that’s not for me.”

The issue extends beyond her ZIP code — schools with a 2013-2014 ranking of four or five stars are mainly in the suburbs, according to an analysis by Opportunity 180, the harbormaster that recruits charter operators to Nevada.

But move from the wealthier outskirts of the valley closer to the city and those top-ranking schools disappear. Instead, one- and two-star schools take their place.

“It’s fair to say that median home value continues to determine the quality of public school a child has access to,” said Opportunity 180 President Allison Serafin.

The group’s vision is to have an equal distribution of five-star schools across Clark County.

“We believe that every child has the capacity for excellence, and every child has the potential to be an exceptional student,” she said. “However, we also know that there are a myriad of challenges that our children that live in poverty face every day.”

SURVEY DISSATISFACTION

Because the group is a proponent of attracting quality charter operators to Nevada, it is naturally at odds with the Clark County School District.

Its survey of 656 parents found that 65 percent would consider sending their child to another school in their neighborhood if that option existed.

Parents in ZIP codes with underperforming schools were more likely to report the need for more improvements to address overcrowding, quality of teaching and student safety and discipline.

Jimenez has been in touch with Opportunity 180 and spoke at a meeting alongside the nonprofit.

Yet she doesn’t have an opinion for or against charter schools. She is just worried about the future.

“If we don’t tend to this hole that one- and two-star schools are in,” she warns, “it’s going to get bigger.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at 702-383-4630 or apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.