Clark County schools operating with shortage of psychologists

Andrea Walsh always dreamed of being a psychologist, but she started out teaching because her parents argued that she wouldn’t get a job with just a psychology degree.

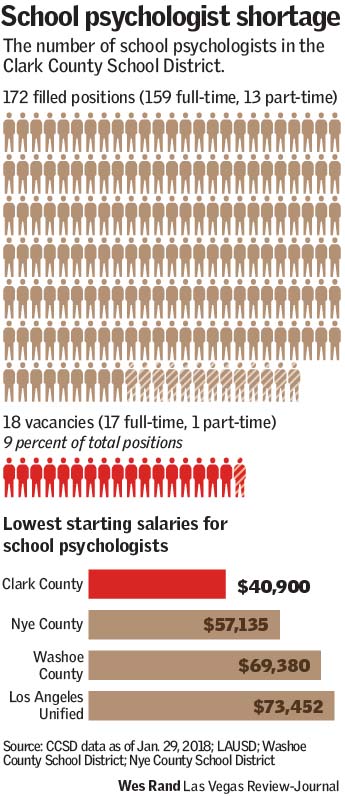

She went back to school, however, and today is one of the Clark County School District’s 172 licensed school psychologists. The district separately contracts with three others.

Click for a larger image

The problem, according to experts, is that there aren’t enough people like Walsh. The district is currently short 18 mental health care providers for the district’s roughly 320,000 students, in large part because of the demands of the job and the fact that the salaries aren’t commensurate with their level of education.

The shortage is similar to those the district faces in other occupations, such as teachers and bus drivers, but it could carry greater risks.

The openings mean current psychologists must spend more time processing case files, mainly special education paperwork, meaning they can’t provide mental and emotional support to all children in need, according to the Nevada Association of School Psychologists. That’s worrisome at a time when the district is seeing an increase in the number of documented suicidal thoughts among students.

“There are a lot of risk factors that our students are experiencing here down south,” said Katie Dockweiler, president of the state group. “Schools are coming to us for more because they realize the value of what we have to offer. But given the constraints of our numbers, we can only do so much.”

Fighting a national problem

School psychologists provide a range of services for students, including special education assessments, suicide prevention and more.

“We can decrease bullying. We can assist with those efforts. We can assist with decreasing the disciplinary issues that are on campus,” Dockweiler said. “School safety, school culture — all these things are things that we are able to assist with.”

But that assistance is difficult to render when the corps is stretched thin, she said.

The National Association of School Psychologists recommends a psychologist ratio of 1 for every 500 to 700 students. In Clark County, that ratio is about 1 to 1,880 students, according to rough calculations using an estimated student population. The state association, however, estimates the ratio at 1 to 2,100 students based on a survey of 44 psychologists. Statewide, the group says, the ratio is even worse, at 1 to 3,500.

And Nevada is not alone. Combating the shortage is one of the national association’s most critical priorities.

“The shortage has been an issue, but it is an increasing issue over time,” said Eric Rossen, the national group’s director of professional development and standards.

The shortage may not end soon. A 2014 study by University of South Florida researchers concluded that the field will continue to experience shortages of trained psychologists through 2025.

Shortage of graduate programs

Part of the problem, Rossen said, is a dearth of school psychology graduate programs to adequately build the workforce.

Most people in the field earn an education specialist degree — which is more intensive than a master’s — and perform a one-year immersive internship, according to Rossen, who explains that school psychology is different from clinical psychology.

“(There’s) this incorrect belief that people who work in independent practice can seamlessly work into the school system, whereas the laws, the diagnostic processes, and even categories — they’re entirely different,” Rossen said.

UNLV’s graduate school psychology program is the only school psychology program in Nevada, according to Katherine Lee, program coordinator for the education specialist degree path.

It has about 55 students in its doctorate and specialist degree programs and just three faculty members, she said.

“We’re still kind of brainstorming the best, most effective ways to reach out to … undergrads or even CCSD employees,” she said.

While awareness is a hurdle, the demands and financial realities of the job can be even bigger, Lee said.

“Because there’s a shortage, we have more work, so it’s really easy to burn out in this field,” Lee said. “We have deadlines that we need to meet federally and also according to local statutes. That makes our work … really overwhelming at times.”

Salary scale

At the same time, the lowest possible starting salary for school psychologists in the Clark County district is $40,900 — the same as a starting teacher’s pay.

That’s lower than the low-end pay of $57,135 in Nye County and $69,380 in Washoe County. Nationwide, the national group estimates the average starting salary at somewhere in the mid or upper $60,000s.

The Nevada Asssociation of School Psychologists is hoping to change that, arguing for a more competitive pay scale that’s separate from the current Professional Growth System salary schedule. That, they note, could entice more people into the field.

“I work with some amazing special education teachers, and I’ve said, ‘You should look into becoming a school psychologist. You’d be great at it,’” Walsh said. “But they say, ‘I’d make the same amount of pay and go back to school.’”

A district spokeswoman said in a statement that salary increases would have to be negotiated during contract talks with the Clark County Education Association, which represents the psychologists as well as teachers.

In the meantime, Walsh and others in the field forego other lucrative jobs for one main reason: their impact.

“There’s a couple of kids every year that I never forget about, because I know I made a difference,” Walsh said. “It’s what kind of keeps you going back for more.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

"The farther away you go from that ratio, the fewer services that are available to kids. Those services promote learning, to help students learn, to help teachers teach. They support the mental wellness and overall functioning of schools." —Eric Rossen of the National Association of School Psychologists, on the importance of sticking to the recommended 1-to-500-700 ratio of psychologist to students.