Nevada, facing a shortage, struggles to keep teachers

Sara Boucher vividly remembers her first year of teaching in the Clark County School District five years ago. She was 22, fresh out of college, and had no idea what she was doing.

“I would stay every night until 7 or 8,” she said of her time at Schorr Elementary. “And then every weekend, I would have to go in. There was just so much to be done.”

There was a lot of crying, Boucher said. Her migraines were so bad that she went to see a neurologist.

“I was a baby still, so it was very, very, very stressful,” she said. “A lot of pizza and soda. Lots of Mountain Dew to keep me up.”

Boucher made it through the first five years. Beyond that, research shows, 40 percent to 50 percent of new teachers will leave the profession.

Now, she’s decided to leave and plans to move to New Mexico, where her boyfriend is working toward his doctorate. Her decision illustrates one of many reasons teachers may leave a school district.

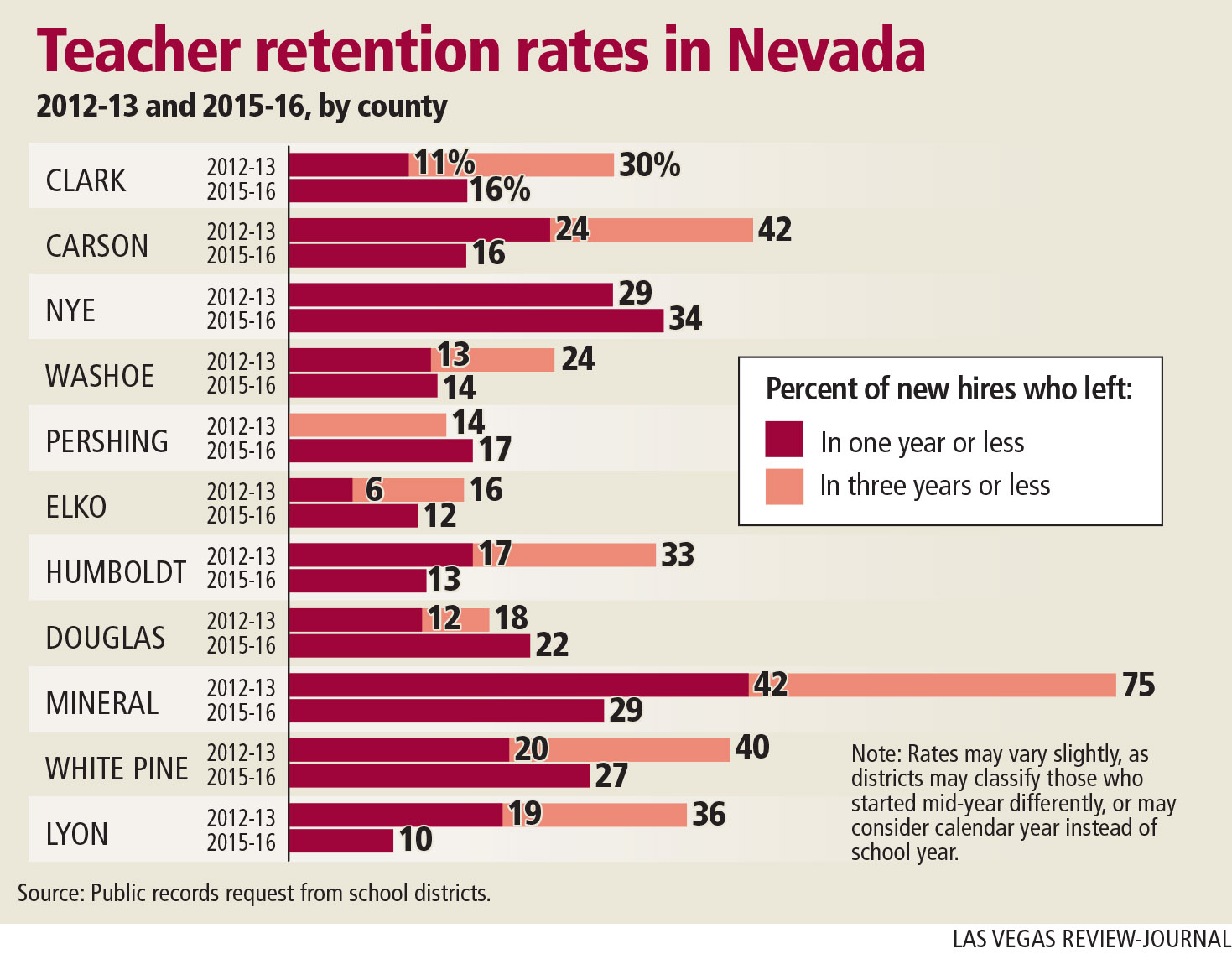

A Las Vegas Review-Journal analysis of teacher turnover data found that 16 percent of teachers who began in the Clark County School District in 2015-16 left within one year or less.

That falls in the midrange of the same data for 10 other school districts in the state, which had turnover rates ranging from 9.5 percent to 33.9 percent for that same year.

After three years, the turnover rate increases significantly; 29.5 percent of those who started in 2012-13 had left Clark County.

Amid the overwhelming burden of addressing Nevada’s teacher shortage, the data point to an even larger challenge for districts: how to retain the teachers they try so hard to recruit.

“Clark County is sort of famous for having these recruitment efforts all over (the country),” said Richard Ingersoll, a University of Pennsylvania professor whose research includes teacher turnover. “But you have to ask, ‘Well, do you retain these people? Do you keep them?’ ”

DRAWING TEACHERS IN

In Clark County, retention efforts start as soon as someone is hired, said Meg Nigro, executive director of recruitment and development.

Over the summer, new hires are connected with a fellow teacher to answer questions about working and living in Las Vegas, Nigro said. The district also offers social activities before the school year starts and throughout the year: hosting hikes at Red Rock, a day at the Mob Museum and more.

“We try to really ease those kinds of social anxieties,” she said. “As humans, it’s the basic needs that we’re worried about first that have to be satisfied. If I’m paranoid, I don’t know anybody in this town, how am I going to get started?”

Clark County’s one-year turnover rate of 16 percent is higher than a similar 2015 statistic from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Nationwide, the center found that only 10 percent of teachers who began in 2007-08 were not teaching the following year. After three years, that number rose to 15 percent.

Yet those national data examine beginning teachers who left teaching entirely the following year. Those who left Nevada’s school districts may not be beginners and may still be teaching elsewhere.

The 11 districts that provided data also may count teacher departures differently, depending on when they started in the school year or other factors. The data may include teachers who retired or whose positions were eliminated.

Ingersoll, whose research includes the five-year turnover dilemma, said teacher salaries are not the only factor for turnover.

Student discipline also can play a role.

“Some schools do a much better job of dealing with their student behavioral challenges, and some don’t,” he said. “And those that don’t have far higher teacher quit rates.”

BEYOND LAS VEGAS

The challenge of keeping teachers isn’t unique to Clark County. Districts statewide can find themselves caught in a churn of turnover that further exacerbates their ability to fill vacancies and address staff stability.

“I think that people in Nevada are definitely worried about their retention rates,” said Ruben Murillo, president of the Nevada State Education Association.

Teachers will leave if they don’t think they’re getting enough support in their job, he said. The strains of testing, he added, can also play a role.

“I think there’s a whole mix of issues there that are preventing teachers from staying,” he said. “A lot of them get fed up, they decide ‘this isn’t for me,’ or they decide this isn’t a career they want to pursue for 15, 20 years or more.”

Jose Delfin, associate superintendent of human resources in the Carson City School District, strives to keep new out-of-state teachers for three years.

“If we don’t retain them past three years, they’re going to follow their heart back home,” he said. “If I can get them here for three years and stick, and get them to the fourth or fifth year, they’re here to stay.”

In Northern Nevada, he said, there is more of an exchange of teachers between districts.

“For instance, Carson City doesn’t have as many apartments as Reno, so a lot of our staff live in Reno,” he said. “So as soon as they can find a job in Reno, they go.”

Delfin, a former Clark County School District administrator, said Carson City’s higher cost of living and lack of affordable housing may factor in the district’s attrition rates.

Yet the district increased its starting salary to $40,000 with the hope of attracting more teachers, Delfin said.

“Retention for us means that we’re doing everything we can to support teachers,” he said. “And that means from the time that they’re in the classroom we give them as much help with curriculum, with resources they need.”

But in Las Vegas, he noted, other personal dynamics are in play.

“My own theory about Vegas is they’re young, they’re energetic, they get their feet in the door in Vegas,” he said. “And then they miss something that’s greener, they miss home — and then they bolt.”

STATEWIDE EFFORTS

At the state level, Assembly Bill 77, up for debate this legislative session, would make it easier for educators to teach in subject areas beyond their original expertise.

The establishment of the Great Teaching and Leading Fund, which boosts professional and leadership development, may also help in retaining educators.

“We know that a big factor in whether or not teachers stay is the opportunity that they have for leadership,” said Dena Durish, the state’s deputy superintendent of Educator Effectiveness and Family Engagement.

But on a more focused level, Durish questioned the turnover rates for more challenging schools.

“At the state level, we’re focused on retention of teachers in schools where there’s a high population of students in poverty, students with a second language and minority students,” she said.

Looking back, Boucher said all the stress was worth it. She has a strong message for new teachers: Persevere.

“You know what, my first year sucked,” she said. “The first year is your worst year. And your second year might not be that great. But just stick it out.”

She thinks back to why she became a teacher, and it wasn’t for the money.

“You don’t get into teaching if you want to work a normal 9-to-5 job, because that isn’t teaching,” she said. “But if you love kids and you love making a difference, then stick with it.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

RELATED

Washoe officials say they don't plan any teacher layoffs amid budget woes

CCSD struggles for solutions to special education teacher shortage

New 9-step strategy aims to help Nevada deal with teacher shortages

Clark County, Nevada pursue more teachers as new school year looms

New UNLV program wants more teachers of color in Clark County schools