Retiring leader of state schools hopeful about future

Cuts, cuts, cuts.

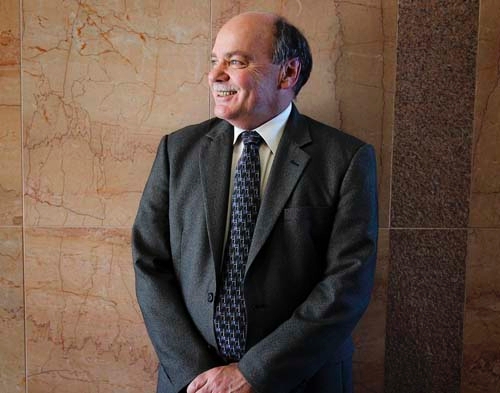

"It seems like that's all I've done for 11 years," said Keith Rheault, reflecting on more than a decade of decisions as Nevada's superintendent of public schools. "All we've been doing is playing defense."

But Gov. Brian Sandoval promises a reprieve next year, vowing to hold the line on school funding. Nevada, which has struggled to keep up with one of the country's fastest growing student populations, would finally have a chance to catch its breath, said Rheault, who speaks from years of experience matched by only two other current state superintendents in the nation.

"Growth was a detriment more than anything," the retiring state superintendent said of Nevada's low student performance ranking when compared to other states. "With stability will come improvement."

Rheault, 57, considers it all as he ends his tenure at the helm.

"There's no good time to leave, but this is as good as it gets," he said Thursday, shortly after flying into Las Vegas for his last Nevada Board of Education meeting. Rheault is retiring April 2 after 25 years with the state education department.

His goal is to step down with Nevada schools heading in the right direction. He plans to retire a month after signing off on a wave of reforms to be implemented if the federal government approves Nevada's request for a waiver from the much-criticized requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act.

Rheault has been the state's head of public schools since 2004, but has ushered the state through some major shifts dating back to 1986, when he joined the Nevada Department of Education as a director of agricultural education.

Rheault grew up in the fertile farm country of the Red River Valley near Fargo, N.D., working on his grandfather's farm growing soybeans, sunflowers and grains.

Because of that experience, Rheault has always championed integrating career and technical training into public education. He developed the state's original vocational education program after earning a doctorate in agricultural education from Iowa State University, said veteran Board of Education member Dave Cook.

These vocational schools -- now numbering less than a dozen -- have proven successful with high graduation rates, low occurrences of discipline problems and student career success, he said. That's because students attend these schools to pursue their passions in culinary arts, aeronautics, engineering and other fields in addition to the basics.

"To me, that's an answer for public schools," he said. "All have waiting lists."

Rheault's retirement, in itself, marks a major shift in Nevada education. Beginning with Rheault's successor, the governor chooses the state superintendent of public instruction instead of the Board of Education, and the governor alone can replace the superintendent. Critics have said that has some negative implications.

"If you don't follow what the governor wants, I don't know how long you can get away with that," Rheault said. "That will make it much more political than it has been."

For example, the state is rolling out a new framework, which ranks schools mostly based on student performance. Gov. Brian Sandoval wanted schools to be given letter grades, from A to F. But school district officials thought that would be punitive instead of constructive and argued for a system of one to five stars.

Rheault weighed both arguments and sided with the districts.

"Keith always had a close working relationship with district superintendents, understood what they needed," said Cook, who was on the Carson City School District board from 1988 to 1996 before joining the state board. "He always did the right thing, instinctively, intuitively."

The new superintendent appointed by Sandoval, James Guthrie, must defend the governor's programs, unlike Rheault who "didn't have the threat of being fired," Cook said, adding: "Education is going to change."

Oregon is going a step further, with its governor also taking on the role of state superintendent.

"Right or wrong, my take on the job was being a ref" for the districts and the state, said Rheault, noting that he wasn't one to push programs on districts.

If districts don't support a program, it won't succeed, he said.

Rheault was always a "voice of reason," Cook said. "Keith was someone everybody trusted."

That's why the board supported him from start to finish.

Now, it's time to take a break, Rheault said. "I think I've been working since eighth grade."

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at

tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.