UNLV’s student housing upgrade comes at expense of low-income families

U District beckons UNLV students with glossy pamphlets celebrating college life, a pitch punctuated with images of hip, attractive 20-somethings frolicking and posing for selfies.

Study rooms. Movie nights. Sleek, spacious living areas. A swimming pool with cabanas.

“Why live anywhere else?” the ads say.

The student housing project — which aims to bring more than 3,000 beds to the north edge of campus by 2026 — is a linchpin for UNLV’s efforts to shed its reputation as a sleepy commuter school.

But dozens of low-income families — hundreds of people — stand in the way of that estimated $200 million vision: U District is being developed inside an aging apartment complex, where 250 units are being emptied to make way for upperclassmen who can afford upgraded digs with bigger price tags.

“They didn’t even offer me the option to renew,” said William Wolfs, a graduate student who was ordered last month to pack up and move out within 30 days before his yearlong lease ends Monday. He had lived at the complex for eight years.

Developers plan to turn Wolfs’ apartment into a dorm-style unit, charging $350 per bedroom — or a total of $1,050 — for a three-bedroom home that cost Wolfs $750.

Managers earlier this year asked him to switch units to make room for new construction, and relocation costs have added up quickly. Wolfs and his son Eli, 5, live on a researcher’s stipend of $20,000 per year.

“It’s not cheap,” he said.

GOING RESIDENTIAL

UNLV has long yearned to lose its image as a commuter campus by transforming its neighborhood into a more inviting home for students. The dormitory-style housing project, developed by local real estate firm The Midby Cos. with UNLV’s aid, is a big driver for those plans.

Within the past year, apartment management began closely watching when leases expired in anticipation of delivering 30-day notices to vacate.

“While we understand that change is difficult for the existing residents, we have and will continue to work with them in order to identify alternate housing options,” project leader Eric Midby wrote in an email Friday afternoon. “All communications with tenants have been in accordance with the terms of their lease agreement.”

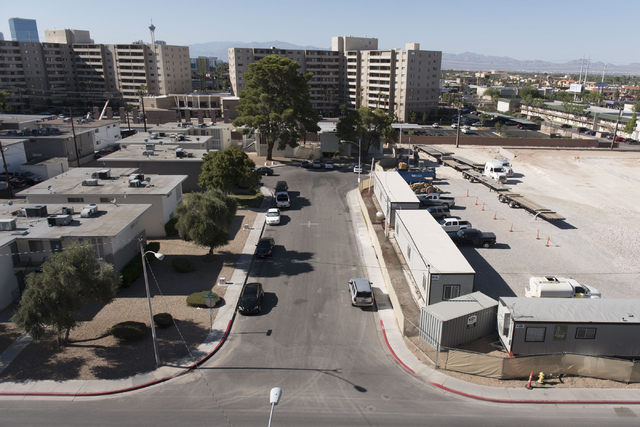

UNLV bought University Park from Wells Fargo & Co. for $18.5 million last year, with Midby investing the rest to manage and rebuild apartments at the 14-acre site. By late next year, the company plans to open a five-story, $76 million facility called The Degree, which will have 226 apartments with 758 beds.

“We purchased this land with the intent of supporting UNLV students,” UNLV finance boss Gerry Bomotti said, responding to questions about the displaced tenants. “We have always been sensitive to the speed of the transition, as has the Midby team.”

Crews began tearing down a 116-unit section of University Park in February, and they began construction in May. The Midby Cos. still oversees 160 remaining units, which it is renovating and rebranding to draw more students. Midby plans to tear the old units down in the next decade to make room for as many as 3,000 U District beds — an effort estimated to cost more than $200 million.

Administrators are hopeful that U District will flourish thanks to high demand.

“The kind of traditional notion of UNLV is (that it is) a great university but kind of more of a commuter campus,” President Len Jessup said at a ceremony this month celebrating the project’s kickoff. “We have no more room. … We have a waiting list for students who want to live around campus.”

‘I WANT TO STAY’

University Park residents, meanwhile, have been hit with a flurry of 30-day notices to leave. Four families said last week they wish to stay but can’t afford higher rates. Two others said they just want out because their homes have fallen into disrepair under new owners, who seem more eager to kick them out rather than fix leaking walls, moldy carpets and broken air conditioning units.

Rodrigo Moller, an assistant manager at the property, said the company is trying to work with people struggling to move out. Moller and General Manager Chad Clark declined to elaborate, referring inquiries to Houston-based Asset Campus Housing, which has been hired by Midby to oversee the property. Asset Campus Housing Vice President Jason Fort did not respond to messages this week.

“I’m not very informed about all of this, and I feel blind trying to understand,” José Cruz Durán González, 62, said in Spanish. “I don’t know if this is a trick to get us out.”

Durán González’s wife is pursuing U.S. citizenship, and switching addresses would draw out the process. Following a suggestion on his 30-day notice, he visited the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada, whose attorneys are trying to extend his stay by at least a month.

A retired fry cook who most recently worked at Luxor, Durán González earns about $1,244 a month and spends $575 for his two-bedroom apartment. That rate would shoot to $750 under the new rent structure.

“If there’s an option, I want to stay,” he said. “But it’s too much — with that money I can pay three or four bills.”

THE PERILS OF PARTNERSHIPS

UNLV has increasingly turned to the private sector to develop and manage housing — officials say this allows the school to dedicate most of its funding to academic buildings and facilities.

The school, for instance, is working with another company to develop a parking structure across from Greenspun Hall, near Maryland Parkway and University Road. Intent on rejuvenating the area around UNLV, administrators have pursued at least three major partnerships with private investors since 2012 to build apartments for students and retail space. Two of those failed because of financing problems.

Experts say those partnerships can be beneficial, but may involve risks for universities.

“A college is a nonprofit, and (its) goal is service,” said Christine Drennon, a sociology professor at San Antonio, Texas-based Trinity University who specializes in urban geography and community development. “A for-profit’s institution’s goal is to make profit. Those two things don’t necessarily go hand in hand. Sometimes they’re opposites.”

Contact Ana Ley at aley@reviewjournal.com or 702-224-5512. Find @la__ley on Twitter.