Adolph Sutro’s name lives on at various valley sites

By the early 1950s, when the Bonanza Village neighborhood was being built, Las Vegas was coming into its own as a resort community, but it still traded on its image as a Western frontier town.

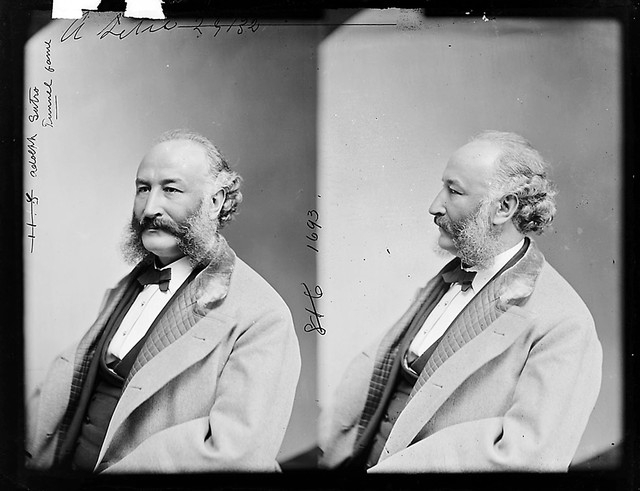

The inspiration for the street names come from Northern Nevada’s rich mining history, including Sutro Lane and Sutro Way, an extension adjacent to the Bonanza Village subdivision. Sutro Lane and Sutro Way were named for Adolph Sutro, one of the more colorful characters from that place and era.

“Of course, in Nevada, we know him for the Sutro Tunnel,” said Mark Hall-Patton, administrator for the Clark County Museums. “But he was a much bigger figure in San Francisco.”

Hall-Patton’s personal collection of historical artifacts includes a short biographical book published in 1895, when Sutro was the first Jewish mayor of San Francisco.

The book’s title is “Adolph Sutro: A Brief Story of a Brilliant Life,” by Eugenia Kellogg Holmes. After the book cites the details of Sutro’s birth, Holmes begins praising the man in florid terms:

“By the birth of that son, the City of San Francisco, the State of California, and the world of which these municipalities form so important a part, is enriched to a degree inestimable, since the qualities which form nobility of character are incalculably precious and therefore beyond the judgment of men.”

Sutro was born in Aachen, Prussia, in 1830. Aachen is now the westernmost city in Germany. He came to San Francisco in 1850 and was involved in several businesses. He became a store owner, married and had his first child before moving to Nevada in 1860 following the call of the Comstock Lode. He built an ore mill in Dayton, where several local businesses now bear his name.

He studied engineering in Prussia and proposed building a tunnel to drain water and deadly gasses from the mines of the Comstock Lode. The Sutro Tunnel was designed to start at the base of Mount Davidson and angle up to reach the lower mine shafts owned by multiple companies. As difficult as that proved to be as an engineering feat, the trick was raising money for the enterprise.

The wheeling and dealing it took to raise the money and form the Sutro Tunnel Company honed skills that would serve him well in years to come. By 1865, he had gained state and federal approval for the project and selling stock in his company. He developed the town of Sutro near the base of the tunnel. Resistance came from the Bank of California, which controlled much of the Comstock. The Sutro Tunnel would not only drain the tunnels, it would provide an alternate route for ore and miners.

Construction of the tunnel began in 1865. Funding was still tight in the early years of construction, but when a fire killed dozens of miners in April 1869, Sutro took advantage of the event, called the Yellow Jacket Disaster, to drum up support for his tunnel. Although his claim that his tunnels would have saved the miners is now deemed unlikely, it brought him support from miners who invested in the project.

The 1874 U.S. Senate race pitted Sutro against William Sharon, the Bank of California’s representative in the Comstock area. Sutro lost in part because Sharon had taken the precaution of buying one of Virginia City’s newspapers, the Territorial Enterprise, and replacing an editor who had written articles opposing him in a previous election.

By the time the tunnel was completed in 1878, it was no longer as relevant as it would have been when it was conceived. The mines were deeper than the Sutro Tunnel by then, and water could not properly drain into it, and better pumps had been developed to drain the tunnels.

“The tunnel is still there,” Hall-Patton said. “The entrance is on private property, but I’ve been able to visit it and go inside. It’s still in pretty good shape.”

Sutro sold his interest in the company and returned to San Francisco, where he made profitable investments in real estate. Among his more notable purchases were tracts of land on the western shore of San Francisco, including the iconic Cliff House restaurant.

In 1887, four years after Sutro bought the restaurant, it was damaged by an accident when a ship carrying dynamite crashed and exploded on the cliffs below. He rebuilt it, but a fire caused by a faulty flue destroyed the building in 1894.

He rebuilt the restaurant into a seven-story Victorian chateau and added the Sutro baths north of the restaurant. By the time the landmark structure was built in 1896, Sutro was at the end of his two-year term as mayor. He ran as a populist “anti-octopus” candidate, a term referring to opposition to monopolies.

Sutro died in 1898 and left significant gifts to the city. His extensive library was destroyed in the fire following a 1906 earthquake, but his name remains on many landmarks in the city, including Mount Sutro, Sutro Tower and Sutro Heights.

In Las Vegas, Sutro Lane intersects with Sharon Road, named for his political rival.

The Streets of Bonanza Village are named for Nevada mining history. Goldhill and Virginia City avenues are named for cities near the Comstock Lode. Ophir Drive is named for the Ophir Mine in Virginia City. The remainder of the streets are named for people who were significant in the history of the Comstock Lode. In addition to Sutro and Sharon, streets are named for Henry Comstock, the namesake of the lode; Darius Ogden Mills, founder of the Bank of California; James G. Fair, a mine owner who served in the U.S. Senate; and William C. Ralston, operator of the Bank of California during the 1860s and ’70s.

Contact Paradise/Downtown View reporter F. Andrew Taylor at ataylor@viewnews.com or 702-380-4532.