Hispanics putting trust in police’s HART program

For years, the mere sight of a police cruiser terrified the 45-year-old woman.

They're going to deport me, she thought. Or at least hassle me.

"Every time they stopped next to me, or behind me, or in front of me, I'd think, 'Oh, God, they're going to arrest me,' " the woman, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who asked not to be identified, said in Spanish.

Had she been the victim of a crime -- or a witness -- during those years, she probably wouldn't have reported it to the police.

It was with people like her in mind that an officer with the Metropolitan Police Department had the idea, a little over a decade ago, to form a special unit dedicated to investigating crimes against illegal immigrants and building trust between officers and the local Hispanic community.

It's tough to solve crimes, after all, if people are afraid to talk to you.

That pilot program, called the Hispanic American Resource Team, or HART, has grown from two to six full-time officers and garnered local and national praise for its work.

The National League of Cities this year profiled HART's "good practices" in a report highlighting successful public safety programs in immigrant communities across the nation.

Miscommunication and distrust often strain police-immigrant relationships essential for effective law enforcement within the entire community, the report said. It also said local police, faced with significant demographic changes in recent years, successfully used HART to help "serve and protect a culturally diverse community, including the segments of its population hindered by language barriers and fear of the police."

HART ROOTS

Randy Sutton recognized the problem shortly after being transferred to the Downtown Area Command, where the population is largely Hispanic.

The then-sergeant went out on a violent call where nobody would tell him anything because they thought they would get deported.

"They were more afraid of us than the bad guys," said Sutton, who is now retired.

He figured plenty more people were getting hurt or taken advantage of without police ever finding out.

Even when they did talk to police, "we weren't getting the real story," Sutton said.

People didn't understand that local police didn't enforce federal immigration laws.

Sutton proposed creating a team of Spanish-speaking officers to work exclusively with the Hispanic community and spread the message. At the time, about 20 percent of Clark County's population was Hispanic. Today, that population has grown to more than 29 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The police department took two young Hispanic officers off their patrol duties and turned them into investigators, Sutton said. HART was born.

"They felt like they were on a mission," Sutton said. "They knew they were doing something important."

It wasn't long before the small team began building successes, Sutton said.

"We got people selling fake green cards. Landlords stealing from their tenants. Lawyers taking advantage of people who didn't know better."

Soon, HART was raking in federal grant money to support it. Sutton received the department's "exemplary service award" for starting it. He now counts HART among his proudest accomplishments, saying he gets satisfaction from "seeing helpless people finally get some justice."

HART TODAY

Officer David Cienega joined HART shortly after its inception and is still a member.

In the early days, "it was like pulling teeth to get people to make a police report," he said.

Cienega and a fellow HART member organized an open house for community members.

"Nobody showed up," he said. "They were afraid to go to the police station. They thought it might be a trap."

It didn't help that many immigrants came from countries where police aren't necessarily your friend.

"People would watch out for police instead of police watching out for them," Cienega said.

HART members decided instead to visit schools in the downtown area, talking to parents as they dropped their kids off for the day. They now hold monthly community meetings at several schools.

"The purpose is to establish trust," Cienega said. "Once that happens, people start letting us know, 'Hey, there's some drug activity going on across the street from my house.' We go investigate. We arrest drug dealers, bust chop shops, whatever."

Word spread. People began to realize they could go to the police and the police would do something.

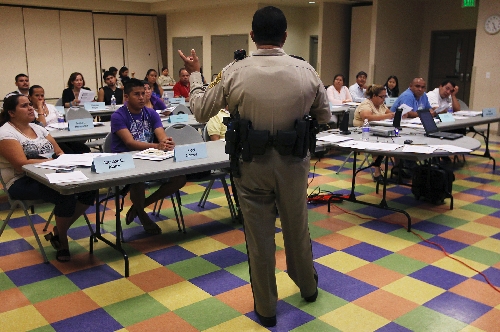

While at the schools, HART members also recruit for the police department's Hispanic Citizens' Academy, an 11-week program modeled after the department's Citizens' Police Academy, except taught in Spanish.

The academy teaches residents about local laws and explains how the police department operates. Much of the content mirrors what police recruits learn in the regular police academy.

People do not have to be legal U.S. residents to enroll in the academy.

The 45-year-old woman -- who used to be terrified of police -- is now about halfway through.

She was afraid to join at first, but curiosity got the best of her. Now the woman, who has lived in Las Vegas for nine years, contributes often to class discussions and laughs with the officers who lead them.

"I have learned that just because I am undocumented doesn't mean I don't have rights and can't get involved," she said Wednesday. "I can be informed and live a secure life."

Ana Coates, a Peru native, graduated from the academy in 2007. Her parents also are graduates. Coates enjoyed it so much she now volunteers to watch participants' children while they attend.

"Some in the Hispanic community are scared to come," she said. "They shouldn't be."

Over all, HART has done a good job building bridges with the Hispanic community, said Vincenta Montoya, a local activist and chair of the Sí Se Puede Latino Democratic Caucus.

"They go on Spanish-language radio to talk about practical things like what you should and shouldn't do if you're arrested," she said. "They're very active."

And the police department as a whole has been "pretty good" about reaching out to local Hispanics, Montoya said.

A TEMPORARY GLITCH

Some of that good will was damaged in late 2008, when Sheriff Doug Gillespie decided to support a controversial partnership between his department and federal immigration officials.

The partnership with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement allowed specially trained corrections officers at the Clark County Detention Center to identify immigration violators and place "immigration detainers" on them. The detainers let local law enforcement hold deportable inmates after they otherwise would be released so immigration officials can take custody of them.

More than 70 jurisdictions nationwide have entered into the partnership.

Critics have said such programs across the nation lead to racial profiling and harm relationships between police and immigrant communities.

Local leaders in the Hispanic community worried the partnership would push members of the immigrant community further into the shadows.

Gillespie said he pursued the partnership because he wanted "to know who is being booked into our jail." Previously, officers didn't have the ability to check the immigration status of inmates and the sheriff's department had to rely on ICE officials to investigate and place detainers on potential immigration violators. ICE officials were not consistent in their approach, Gillespie said.

He said the program would be limited to the jail and would not affect a long-standing department policy that prevents police on the street from asking potential immigration violators about their legal status. He also promised the program would target for deportation only inmates arrested for "higher-level" crimes.

Over the past few years, Gillespie has mostly made good on that promise.

While some of the nation's law enforcement agencies are turning over to federal authorities illegal immigrants who commit even minor offenses, the Las Vegas police department has focused on deporting serious criminal offenders arrested for felonies, according to a study released earlier this year by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan think tank.

Among law enforcement agencies studied by the institute, Las Vegas' program was found to be the most targeted toward serious offenders.

The department's approach over time, along with continued outreach to the Hispanic community, helped ease local concerns.

"A lot of the abuses you saw around the country, you didn't see those types of things happening here," Montoya said. "Over all, they (local police) have done a much better job."

OUTREACH CONTINUES

Cienega faces plenty of questions about exactly how police are connected to ICE. He hands out hundreds of copies of the police department's policy on the matter, written in Spanish.

The policy states the responsibility to enforce immigration laws belongs to federal -- not local -- officials and that local police don't stop, question, detain or arrest anyone based solely on the suspicion that the person is in the country illegally.

"Here, the police watch out for you. You don't have to watch out for them," Cienega said in Spanish on Thursday while speaking to a group of newly settled international refugees as part of a Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada program. "We don't enforce immigration laws. That's not our job. We have no interest in that."

Contact reporter Lynnette Curtis at

lcurtis@reviewjournal.com.

FOR MORE INFO

For more information about HART or the Hispanic Citizens' Academy, call 828-4348 or 828-1999.