World War II left its mark on Las Vegas

As impressive as it is, the new national monument at the northern edge of the Las Vegas Valley doesn’t look like much in satellite images — at least not compared with the giant triangles next door.

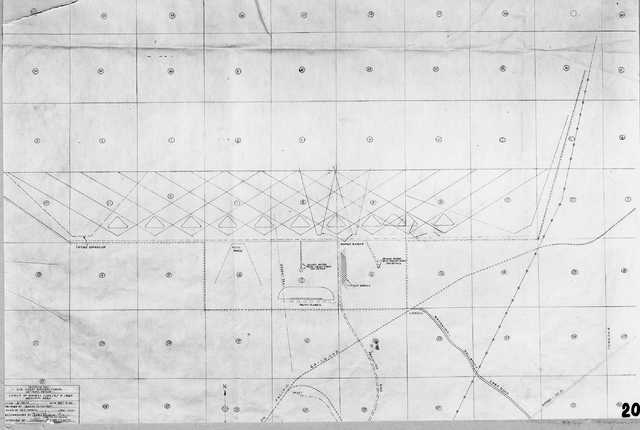

You might never have known about them if not for Google Earth, but there they are: a tidy, evenly spaced row of eight earthen triangles on federal land just off the northern 215 Beltway east of the freshly designated Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument.

These are no small marks in the ground, either. You could fit a small shopping center inside one of the triangles, each of which measured about 950 feet tall and 1,775 feet wide. From end to end, the line of triangles stretches about 5 miles. From the air, they resemble giant wire coat hangers without the hooks.

So what are they and who put them there?

For the answer, you have to travel back 70 years to World War II, when the Las Vegas Valley was a hub for training men to shoot down speeding airplanes from inside other speeding airplanes.

“They were for gunners learning to follow targets,” said Mark Hall-Patton, museums administrator for Clark County. “I think these were the first step in that training.”

The Las Vegas Army Air Corps Gunnery School, a precursor to Nellis Air Force Base, was opened in 1941 to take advantage of the area’s good flying weather, inland location and vast supply of cheap and vacant public property dotted with mountains to shoot into and dry lakebeds to land on.

The school received its first B-17 Flying Fortress bombers in 1942, giving gunners and pilots the chance to train on the actual aircraft they would soon fly into combat.

At the height of the war, the school was churning out 600 gunnery students and 215 co-pilots every five weeks. More than 45,000 B-17 gunners trained there over the course of the war.

Little remains of that massive wartime effort, beyond the strange shapes in the desert floor.

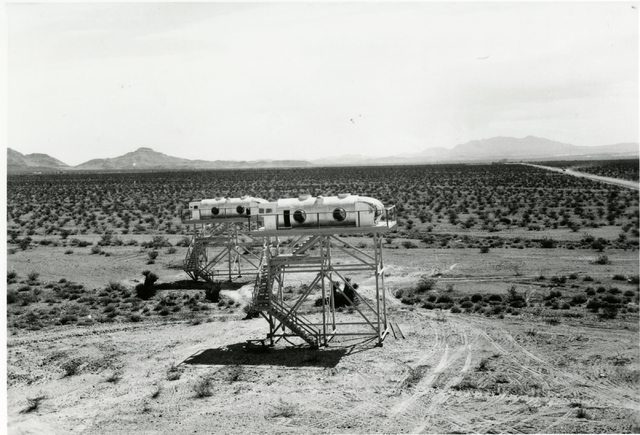

“The triangle was actually tracks where a target went around while being fired on by students in gunnery turret mock-ups similar to what they would have in a B-17,” said Jerry White, historian for Nellis Air Force Base.

The B-17’s defensive armament included two heavy machine guns mounted in a rotating ball turret protruding from its belly to provide protection against attacks from below. Gunners selected for their small size and and lack of claustrophobia rode inside the metal ball.

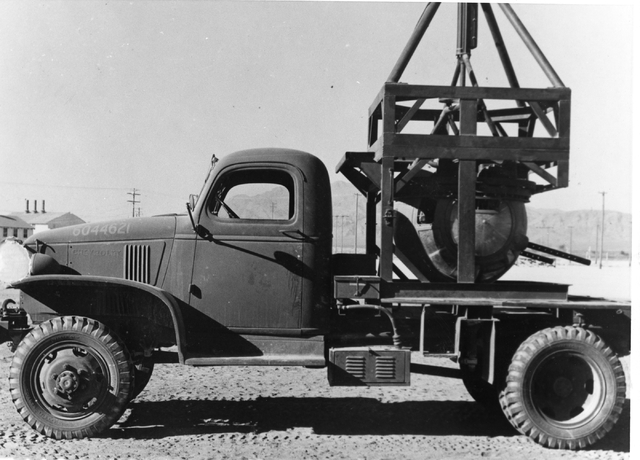

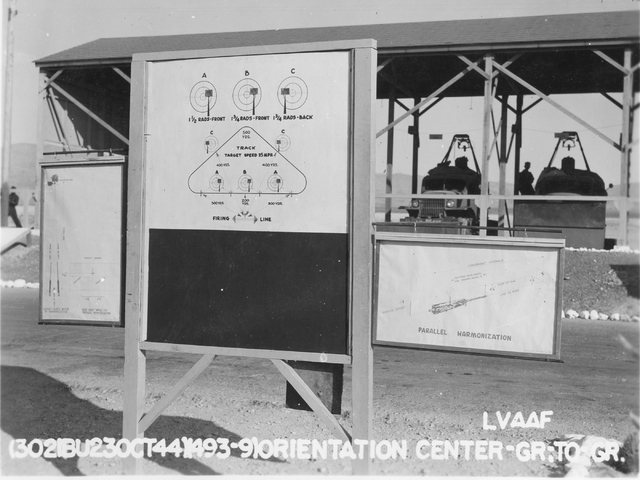

Training the gunners involved suspending a turret on the bed of a truck positioned under an open-roofed structure on the firing line, with trainees shooting at targets up to 400 yards away and zipping along at 25 mph.

Hall-Patton said trainees stared out firing shotguns and eventually graduated to machine guns with the ammunition they would use in combat — .50-caliber rounds with incendiary tracers to help their aim.

Gunners also had to learn the limits of their field of fire — when to stop shooting to avoid hitting other friendly aircraft or their own, Hall-Patton said. “If you went too far, you’d blow off the wing of the airplane or shoot up an engine, all of which are bad things to do,” he said with a chuckle.

White said ground training at the giant triangles supplemented aerial training at Indian Springs, now Creech Air Force Base. There, bomber crews would practice shooting at actual fighter planes outfitted with special armor and lights that would flash on to record a hit, earning the program the nickname “Operation Pinball.”

In March 1945, the school converted from B-17s to B-29 bombers, and the base’s population peaked at 11,000, including nearly 5,000 students, according to a history produced by Nellis.

As the war wrapped up, the gunnery school took on the new role of processing servicemen returning to civilian life. In early 1947, the base was deactivated but came back on line the following year as a pilot training wing and gunnery school as the Air Force adopted jet fighters.

Since then, the triangles have been largely abandoned. One is partially erased by what looks to be a flood control project.

Just don’t expect to visit them in person. There is no public access to the area, which is still a small-arms shooting range for Nellis.

Fittingly, perhaps, the only sure way to see the giant triangles from Las Vegas’ early days as an Air Force training ground is from the sky.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.