Discover ancient artwork, sandstone landscape at Gold Butte National Monument — VIDEO

At Nevada’s newest national monument, you can hike through twisted sandstone sculptures, tour outdoor galleries of ancient rock art, explore a historic ghost town and stare down the Devil’s Throat.

Just don’t forget to pack a lunch.

Exploring Gold Butte is a long and bumpy ride, just like the political journey that led to its designation.

“As you can see, it’s not a place you visit for two hours,” said Gold Butte advocate Kathryn McQuade, one of our guides for a tour of the area on a recent Tuesday. “This is a place you come spend all day. You may choose to camp or whatever.”

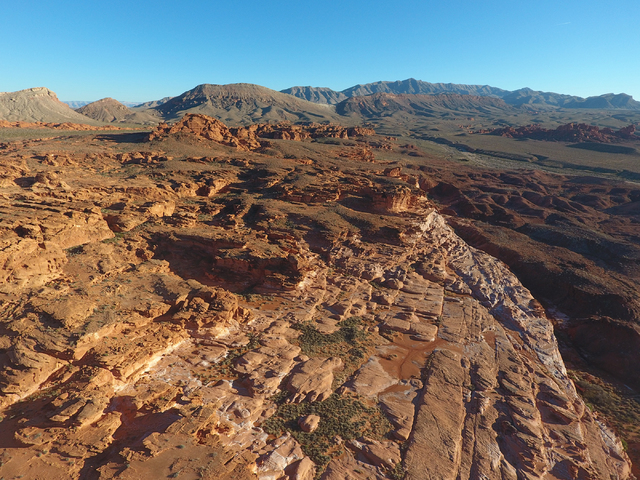

Gold Butte National Monument covers 300,000 acres of remote mountains and desert hemmed in by the Virgin River, Lake Mead National Recreation Area and the Arizona border.

President Barack Obama used his authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to designate the area 100 miles northeast of Las Vegas as a protected national monument on Dec. 28. Before that, Gold Butte was best known outside Nevada as the scene of the 2014 standoff between the Bureau of Land Management and the armed supporters of rancher Cliven Bundy, whose cattle roamed the area without permit or payment for more than 20 years.

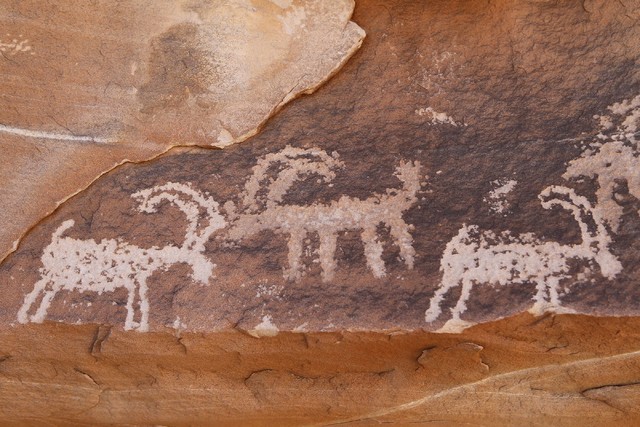

Our tour began shortly after sunrise at the Falling Man site, a sprawling sandstone gallery that draws its name from a single, iconic petroglyph of a human figure tumbling through the air.

Over the course of centuries, people carved symbols on the cliffs where they gathered, hunted, camped and prayed. Their etchings depict “life as they knew it and the land as they knew it,” said Jaina Moan, our other tour guide and executive director of the advocacy group Friends of Gold Butte.

Among the abstract lines and swirls are the unmistakable shapes of desert plants, babies on cradle-boards, human footprints and familiar wildlife, including snakes, tortoises and bighorn sheep.

A federal survey a decade ago counted almost 400 rock art panels and more than 3,500 individual petroglyphs scattered throughout the Gold Butte area, Moan said.

A few hundred feet from the Falling Man, bullet holes pockmark a rock decorated with a single sheep.

A THREAT TO PROTECTION?

At the same time as our tour, Ryan Zinke, Donald Trump’s pick for interior secretary, was on Capitol Hill telling a Senate confirmation hearing that he plans to review Obama’s controversial new monuments — Gold Butte in Nevada and Bears Ears in Utah.

But Zinke pledged to meet with officials in those states before weighing in on whether the Trump administration should try to rescind the designations.

Some legal experts argue that the Antiquities Act is a one-way street, granting the president the authority to declare monuments but not to eliminate them.

Only Congress can change a designation, according to Christy Goldfuss, managing director at the White House Council on Environmental Quality.

Newly sworn-in U.S. Rep. Ruben Kihuen, D-Nev., is promising to push back against any attempt to overturn Gold Butte’s protected status.

Kihuen flew over the monument in a helicopter on Jan. 18 during a tour sponsored by the Nevada Conservation League. The experience left an impression on the congressman, who unseated Rep. Cresent Hardy, a Republican and staunch opponent of the monument designation.

“This is one of our national treasures,” Kihuen said afterward. “I want to be able to take my kids out there someday. I want them to be able to take their kids out there.”

Nevada Democrats introduced five separate Gold Butte protection bills that died in Congress before then-U.S. Sen. Harry Reid and Rep. Dina Titus began pressing Obama to set aside the area.

Top Republicans from the Silver State blasted the executive action, calling it an abuse of power that will unfairly restrict state and private use of public land.

To Moan, though, Gold Butte is just the sort of place envisioned by the Antiquities Act. Literally etched on its walls are the stories of people who moved across the land for thousands of years, she said.

Elsewhere in the monument, researchers have found fossilized animal tracks from the age of the dinosaurs and before.

“It’s such a treasure of antiquity,” Moan said.

And don’t let her catch you calling the monument a land grab.

“This land was owned by all Americans and managed by the BLM,” Moan said. “Nothing has changed about that.”

LAND OF MANY USES

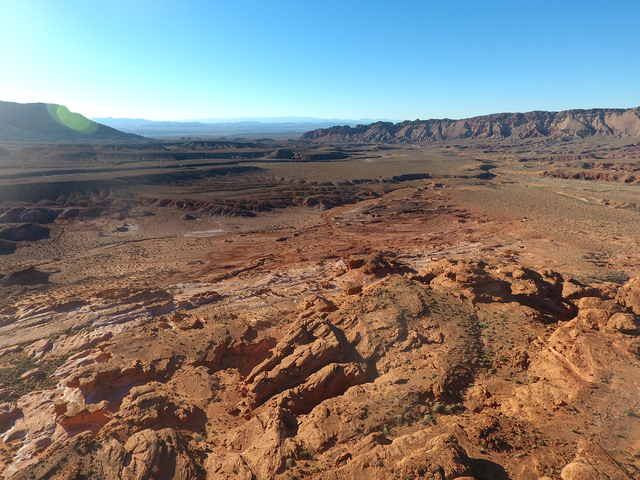

A few miles east of the turnoff to Falling Man, the rough blacktop of Gold Butte Road gives way to a rugged network of dirt roads extending more than 500 miles.

The pavement ends at Whitney Pocket, a popular spot for campers and ATV riders.

There among the sandstone towers, Moan and McQuade led us to a concrete dam built by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps. Narrow stairs lead up the face of the dam and down the other side, though vandals recently pried loose a concrete slab, partially blocking the back passage.

According to McQuade, the Depression-era structure was built to capture water for a nearby horse trough, but the system never worked quite right.

McQuade has lived in Mesquite, just north of Gold Butte on Interstate 15, since 2012. She thinks the new monument could boost tourism in the growing retirement community at Clark County’s northeastern corner.

For the moment, though, Mesquite remains divided over the designation, McQuade said, with vocal minorities on both sides and a larger group in the middle that generally supports the idea so long as the existing roads are kept open and access is preserved for hikers, hunters, horseback riders and ATV owners.

Moan said all those activities are likely to continue under BLM supervision. “Recreation is already the main use of the land, and that’s not going to change,” she said.

The BLM did not respond to a request for information about its plans for the area. So far, there are no signs marking the entrance to the new monument. Moan said even she isn’t sure exactly where the boundary is.

GHOSTS OF GOLD BUTTE

Ultimately, Moan doesn’t expect any big changes at Gold Butte. She’s counting on the monument designation to come with a larger and more steady flow of funding for increased ranger patrols, additional signs and interpretive material and maybe a restroom or two.

“I would also love to see the roads graded,” McQuade added. “What you don’t want is people getting stuck and getting stranded out here.”

From Whitney Pocket, a wide but rocky road leads south to the scattered remnants of the Gold Butte town site, about 20 miles away.

The monument’s namesake community boomed briefly at the dawn of the 20th century, growing large enough to support a post office and about 2,000 residents in tents, but there was never enough gold in Gold Butte.

All that’s left today are some cement foundations, old mining equipment and a pair of headstones belonging to Arthur Coleman and William Garrett, friends and business partners who lingered long after the town died.

One of the graves was dug up sometime in April 2014, right around the time of the Bundy standoff. The exposed remains were collected by the Clark County coroner’s office and later released to a group of area residents who returned them to the ground during a ceremony last March.

From the Gold Butte ghost town, we backtracked roughly 15 miles to Devil’s Throat, another geological curiosity in a landscape filled with them.

The aptly named sinkhole formed when the roof of a cavern collapsed, leaving a widening maw in the open desert roughly 100 feet across and 100 feet deep. A low fence surrounds the hole, at least for the moment. Eventually, Devil’s Throat will swallow that, too.

A FAVORITE PLAYGROUND

Our path narrowed as we angled northwest on Mud Wash Road, which resembles its name, especially after a rainstorm.

A washout canceled our plans to visit Kirk’s Grotto, a keyhole-shaped slot canyon leading to more petroglyph panels. Instead, our final stop was the red sandstone fairyland known as Little Finland.

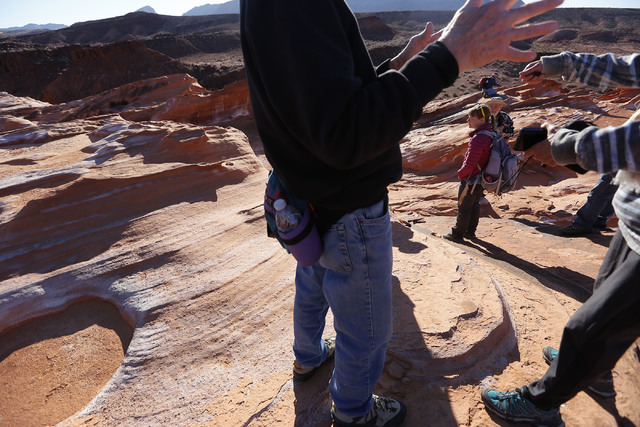

It seemed surprisingly crowded for a Tuesday afternoon. On the way there, we had to pull over to let about a dozen all-terrain vehicles pass going the other way. Then we bumped into a group of retirees from Utah walking among the wildly sculpted stones.

One of the hikers was Vicki Evans, a 15-year resident of the St. George area who said she has visited Gold Butte with her husband and their friends at least 30 times.

They come for the solitude. “You really rarely see other people — except for today,” she said.

Evans said she is fine with the monument designation “as long as they don’t block us from one of our favorite playgrounds.”

Fellow hiker Mary Lou Christy lamented the need for greater protections for Gold Butte, but she said she’s seen some of the damage firsthand. “It’s 1 or 2 percent (of the visitors). They just spoil it for the majority,” she said.

The retirees retired to their trucks and rumbled back down the road the way they came. Soon we would do the same.

First, though, we sat on sandstone from the time of the dinosaurs and talked about what might happen next as the sinking sun bathed Little Finland in an orange glow.

Moan didn’t seem worried by all the anti-monument talk coming out of Washington lately.

“I think so many people supported protecting this place. They’re not going to let it go,” she said. “I think it’s here to stay.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.

RELATED

President Obama declares Gold Butte a national monument

Conservatives in Nevada, Utah howl over Obama's national monument declarations

Reid says he's 'confident' Obama will designate Gold Butte a national monument

Gold Butte called more vulnerable to vandals

Beauty, solitude await in Gold Butte region