Program that puts off child deportations thrives in Nevada

Nevada is among the states with the highest sign-up rate for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, according to a new study of the federal initiative, which gives temporary protection from deportation to some youths who are in the country illegally.

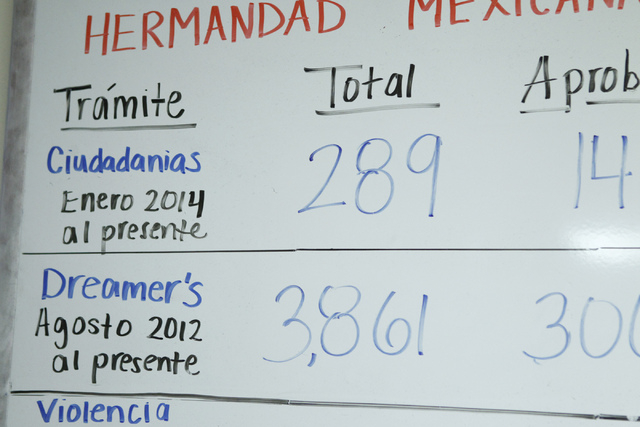

In Nevada, 10,564 people have applied and 9,243 have been approved since the program began in August 2012, according to March data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the most recent available.

Among those that are immediately eligible by meeting all requirements, Nevada has an application rate of 61 percent vs. the national average of 52 percent, according to the study from the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C., think tank.

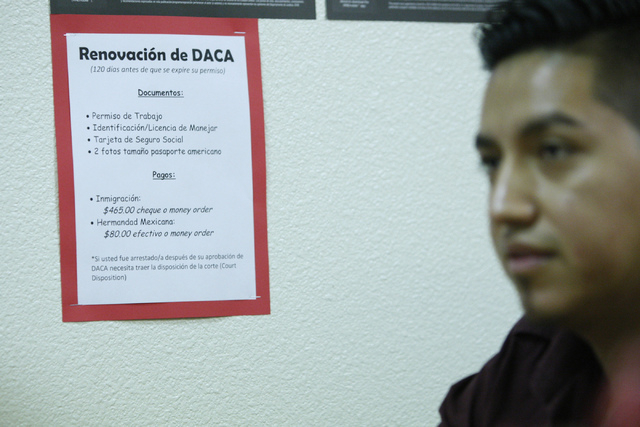

The two-year renewable program allows some immigrants who came to the United States as children to apply for work permits and driver’s licenses and to receive temporary relief from deportation. It applies mostly to people between the ages of 15 and 32. There is a $465 application fee, and applicants cannot have felonies or significant misdemeanors on their records.

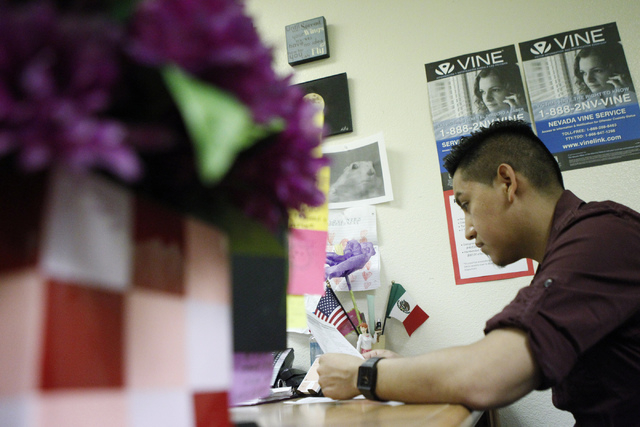

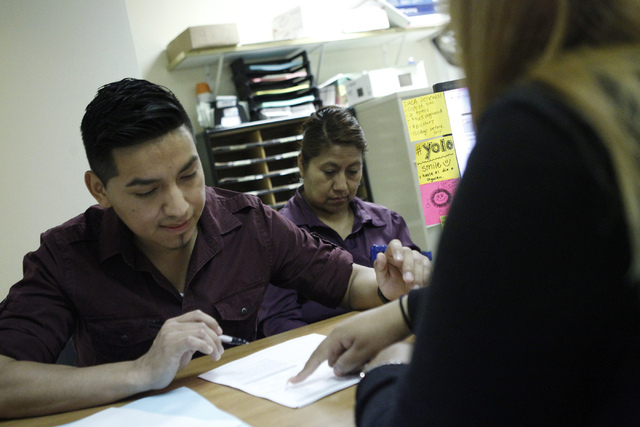

Yadira Favela-Estrada qualified for deferred action in December 2012 and soon after got a job at the local office of transnational nonprofit Hermandad Mexicana, which provides immigration-related services. On Tuesday, she was renewing her application for an additional two years.

“Before DACA, I was just helping my mom clean houses,” she said. “Now I have an income to help with bills, I have a better life.”

Nationally, more than 670,000 immigrants have applied for the program and more than 640,000 have been accepted, according to the most recent data from Immigration Services.

The program was implemented in August 2012 by President Barack Obama, using executive action.

Before leaving for an August recess, the Republican-led House passed a bill that would prevent current recipients from renewing their temporary legal status, but the proposal is unlikely to clear the Democratic-controlled Senate. Republicans have cited deferred action as a reason for the child migrant crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border, but Democrats say the measure would unfairly target law-abiding children and their families.

Obama said in late June that he would take action on immigration reform if a bill was not passed by Congress before the recess. Many believe that he will use his executive authority to expand the program to families.

Some of the factors that affect state deferred-action application rates are “climate of reception,” geographic location, advocacy, age and gender, according to Jeanne Batalova, senior researcher on the study.

States with more restrictive policies for immigrant access to education and driver’s licenses, and that had higher levels of immigration enforcement, tended to have above-average application rates, she said.

Roberto Gonzales, assistant professor of education at Harvard University, and a leading expert on undocumented youth in the United States, agrees that state context affects the program’s impact. For example, New York is an easier place to live as an immigrant because it has reliable transportation, good community colleges and a strong social service infrastructure, he said.

By contrast, rural Georgia has more limited transportation, less access to some universities and a more hostile climate politically for such students, he said. In Georgia, it’s more likely that an immigrant would need to drive, and without proper documentation, they are at risk. According to the study, 54 percent of those immediately eligible in Georgia applied, above the national average.

Gonzales also stressed the importance of outreach, particularly in rural areas.

“Through school, nonprofits, through legal clinics, through private attorneys, it’s really about outreach and infrastructure,” Gonzales said.

In this state, advocacy for immigrants comes in the form of nonprofits such as the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada and Hermandad Mexicana. The local Mexican Consulate office offers financial support to Mexican students who apply, a group that accounts for most applicants.

Hermandad Mexicana helps fill out the program’s paperwork for a flat fee of $80. It regularly registers people in rural communities such as the Amargosa Valley, northwest of Las Vegas, and has registered more than 3,000 of the roughly 9,200 Nevada deferred-action applicants since the program started, the organization said.

Gonzales added that it’s possible Nevada has above-average sign-up rates because the state’s population is concentrated mostly in the Reno and Las Vegas areas. According to characteristic data released by Immigration Services, about two-thirds of the approved applications have come from the Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise area.

The study also said that younger people and women tended to apply more. Batalova said that is because younger people are exposed to more information if they are in school and might even become part of support groups. A college club for youths in the country illegally, the Coalition for the Advancement of Undocumented Students’ Education, was recently started at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Caseworkers at Hermandad Mexicana said the study’s findings were in line with what they see day to day.

Younger students who are in school have an easier time applying because they can readily provide transcripts, said Yoko Calderon, the nonprofit’s outreach coordinator.

“The ones that graduated a long time ago have a hard time proving that they’ve been living here continuously,” said Calderon, referring to the requirement that applicants provide proof of continuous residency since June 15, 2007.

The report also said women applied more than men. One possible reason for this could be that male immigrants more often bypassed school and went straight to work, Batalova said.

In Nevada, about 17,000 people are estimated to be immediately eligible since the program began, according to the study. The think tank’s estimates are based on a 2012 American Communities Census Survey and a 2008 census survey that asked respondents about their legal status.

A primary requisite for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals is that the applicant be enrolled in school or have a high school diploma or GED. It does not allow them to qualify for federal financial aid.

In addition to the roughly 17,000 thought to be immediately eligible, there is a larger segment of the population that could become eligible in the future, pending age and educational attainment. The think tank estimates that an additional 8,000 undocumented youth in Nevada could become immediately eligible by finishing high school or getting a GED and another 9,000 children could become eligible once they turn 15.

Local advocate Astrid Silva of Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada agrees with the study’s findings regarding educational barriers to the program.

“Nevada has the highest rate of dropouts,” Silva said. “A lot of people that might benefit have not graduated high school.”

Contact Alex Corey at acorey@reviewjournal.com or 702-5562. Find him on Twitter: @acoreynews.

Top 10 states by application rates

Among states with the most applications accepted for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, Nevada ranks near the top in application rates for youth who are immediately eligible based on estimates from the Migration Policy Institute through March 2014.

1. Arizona, 66 percent

2. Texas, 64 percent

3. Nevada, 61 percent

4. Colorado, 61 percent

5. North Carolina, 59 percent

6. Washington, 58 percent

7. Georgia, 54 percent

8. Illinois, 50 percent

9. California, 49 percent

10. New York, 49 percent

(U.S. total, 52 percent)

Immediately eligible youth met both age and educational criteria at the time of the program’s launch (i.e., were ages 15 to 30 and were either enrolled in school or had at least a high school diploma or its equivalent). Ranges for estimates based on American Communities Survey sampling and our legal status imputation methods are available in this spreadsheet.