Anglers angry as feds cut bait on Lake Mohave trout stocking program

On the Thursday before Thanksgiving last year, alarms went off at the Willow Beach National Fish Hatchery.

Water from Lake Mohave, which is along the Colorado River about 45 miles south of Lake Mead, stopped flowing into the hatchery’s intake pipes on Nov. 21. This left more than 30,000 rainbow trout, which were being raised at the hatchery for recreational fishing, in tanks without water.

Staff members were able to move about 11,000 of the trout to the lake in what hatchery worker Tom Frew called “a panic release.”

Another 21,000 fish died.

After the incident, and a similar one in August that killed 40,000 trout, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service decided to discontinue the stocking program that previously provided Lake Mohave with hundreds of rainbow trout per month.

The Mohave County board of supervisors called the economic impact devastating and is holding a special meeting Thursday in Kingman to discuss the issue with the local fishing community and Fish & Wildlife service representation.

“It is a very, very important program to our life on the Colorado River,” Hildy Angus, a board supervisor, said. “They made a mistake by [getting rid of] it so quickly and secretly.”

Stewart Jacks, the southwest assistant regional director of the Fish & Wildlife Service’s hatcheries, said it wasn’t a sudden decision, though the timing of the intake pipeline made it seem so.

“The original intent was to get through the season,” Jacks said. That would have kept the rainbow trout stocked through late spring, Jacks said, and given time for the Fish & Wildlife Service to ease people into the idea and look for other solutions. The intake pipe going dry sped things up, he said.

But budget cuts have been a long time coming.

In a review done following an accumulated $6 million loss in appropriations for hatchery operations funding since 2012, the National Fish Hatchery System officials decided to prioritize projects.

For the 2013 fiscal year, the Willow Beach hatchery had approximately $600,000 to work with, Jacks said. That includes operations, utilities, salaries, fish food, fuel and maintenance.

High itmes on the priority list included protecting endangered, native species and fulfilling commitments to nearby tribal communities, Jacks said.

Rainbow trout fell lower on the list because they’re not native to the lake and can’t reproduce once they’re released. Jacks also said the Fish & Wildlife service doesn’t see any revenue from the program — the agencies selling fishing licenses do.

The cost of maintenence also moves the rainbow trout further down on the priority list. One of the hatchery’s two intake pipes is currently unusable, clogged with vegetation with a hole hatchery employees said is big enough for a person to swim through.

“We are putting a Band-Aid on the hatchery system,” service Director Dan Ashe said in a November news release. “Unless we can find a way to cover costs in a more sustainable fashion, the system will eventually need surgery.”

Many in the fishing community are confused why the rainbow trout stocking was the first budget cut, considering the hatchery was built for it in 1959.

“Generally speaking, you drive down on a Saturday and it’s hopping,” said Dennis Wallace, an angler for five decades who frequented Willow Beach in the past. “Now there’s no one.”

Wallace said the marina, restaurant and convenience store at Willow Beach will likely be negatively affected by the rainbow trout’s absence. In a domino effect, other species of fish that preyed upon the rainbow trout, like the striped bass, might leave the area as well.

Garrett Sells, another angler, was saddened that what he considered the best, closest place to fish is gone.

“It was the one place we could always send families to fish for trout year-round,” he said. “They’re definitely ruining part of the fishery doing this.”

It’s not all set in stone yet, Jacks said. The fishing and game agencies throughout the southwest region plan to rally together and see how prorities can be shifted and maintained.

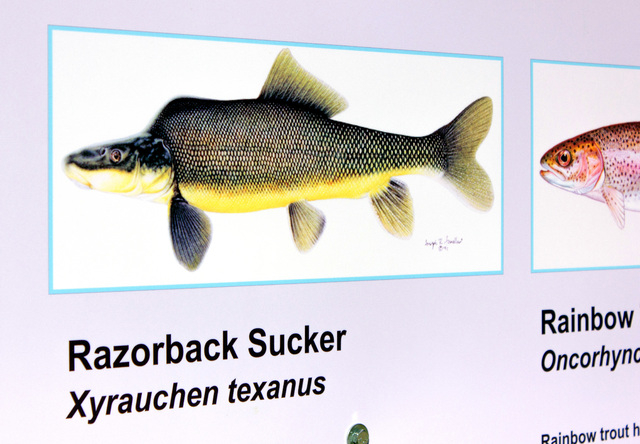

Right now, the Willow Beach hatchery is raising razorback suckers, a native endangered species of Lake Mohave.

Frew said close to 30 visitors per week tour the hatchery facility, where they can see the fish in several stages. When they’re newly hatched, the fish are called “fry” and live in heated tanks indoors. As they grow, they’re transitioned outside into raceways 100 feet long and fed a special diet until they’re over a foot long and released into the lake.

The process, from fry to free in Lake Mohave, can take up to four years.

“That’s why it was so sad when we lost the rainbow trout in November,” Frew said. “We’d been working with those fish for years.”

Thursday’s special meeting will be in the Mohave County Board of Supervisors auditorium, located at 700 W. Beale Street in Kingman, at 9:30 a.m.

Contact reporter Annalise Porter at aporter@reviewjournal.com.