Angry poet laureate carried epic snub to her grave

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

“Among the fifty states, a land unique …

Where contrasts, contradictions, and extremes

Are commonplace.

Where Space,

Is synonym for silence; and the themes

Of Harshness and Hostility

Are manifest; while those

Of Beauty are, too often, unperceived.”

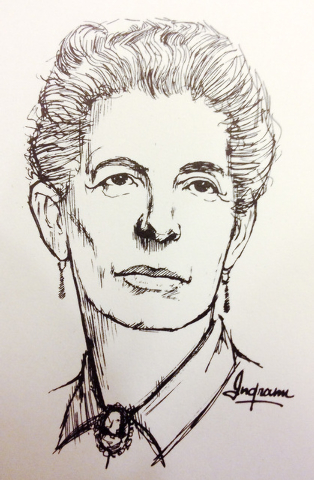

Opening lines of “Nevada” by Mildred Breedlove

CARSON CITY

The story of Nevada poet laureate Mildred Breedlove’s epic ode honoring the state on its centennial in 1964 is a Silver State literary mystery.

Elko cowboy poet Waddie Mitchell’s well-received ode to Nevada written for the state sesquicentennial this year stands in stark contrast to Breedlove’s literary effort of 50 years ago.

Breedlove’s poem, “Nevada,” written by the Las Vegas resident after years of travel and research, did not get the reception she envisioned from state officials despite being widely praised and honored by her peers and others.

In a brief biography by the Nevada Women’s History Project, Breedlove, who died in 1994, said her 29-page poem was suppressed by state officials for reasons that were never made clear.

Breedlove was first appointed as Nevada’s poet laureate by Gov. Charles Russell in 1957. Gov. Grant Sawyer reappointed her to the post in 1959 and asked her to write poem for the state’s 1964 centennial celebration.

Breedlove went on to have the poem published on her own in 1963, but it was never officially accepted by the state. She resigned as poet laureate on Sept. 19, 1966, bitter and angry at the turn of events.

In a letter written in 1968, Breedlove said in part: “I knew ‘Nevada’ was being suppressed as early as mid-June of 1963. But, when I charged this, friends scoffed. … But the suppressing forces underestimated both the work and me. I do not crush easily. My backbone is made of forged steel, and I spit at tigers.

“ ‘Nevada’ was written at the official request of the Governor, and I did it in my official capacity as Poet Laureate. Under these circumstances, the State of Nevada is obligated to put out an edition. It cannot escape this obligation. It will remain until resolved. …”

Her troubles were briefly cited in a July 27 New York Times article on state poets laureate.

Documents connected to Breedlove in the collection of the Nevada Historical Society in Reno shed a little more light on the controversy, but no clear answer is provided in the materials.

In comments to a columnist for the Deseret News in Salt Lake City in 1990, Breedlove said: “What was in it that they didn’t want known? I never did find out. I don’t know today. It was all done under the table, and it’s a very, very long story. I was so bitter over this that I deliberately vacated the post of poet laureate … and moved out of the state.”

In a letter about the same time she wrote: “To this day I do not know who or what was responsible for that suppression. There are two possible sources: This book states facts, some of which probably are very upsetting to decendents (sic) of those who made the history. Among them the Hearsts, Jimmy Fair or other of the Bonanza Kings.

“OR … My voice had become very loud, indeed, and some of the Reds and radicals (in or out of Congress) may have decided to ‘shut my mouth.’ ”

The poem does criticize some of the early participants in the Virginia City mining boom, particularly William Sharon and Fair, “who she called “hateful, unscrupulous and mean.” It also says Sharon and Fair “bought and paid for seats in Congress.” Both represented Nevada in the U.S. Senate.

The lack of official recognition of the poem caused members of the Nevada State Division of the American Association of University Women, on Sept. 12, 1964, to write a letter of concern to Sawyer: “Although there has been a brief public statement of your acceptance of this poem, the poem itself has never been officially designated as the Centennial poem, nor are the people of Nevada aware that this poem exists,” they wrote.

They asked Sawyer to official designate “Nevada” as the centennial poem and “to do all in your power to see to its printing, its distribution, and its use throughout the state.”

That apparently never happened, even though Breedlove was nominated for a Nobel Prize for literature and received the “Narrative Poet Laureate of Nevada” award from the United Poets Laureate International Society for the work.

The poem is written in three parts. The first describes the state’s physical features followed by a section on history that focuses primary on the Virginia City mining boom. The final part talks about Nevada as it existed in 1964 and what may be in store in the next 100 years.

In the book “Literary Nevada: Writings From the Silver State,” Breedlove is said to have been born in Coal Mill, Ark., in 1904. Breedlove and her husband moved to Las Vegas in 1949, where her first collection of poetry, “Those Desert Hills and Other Poems,” was published in 1959.

Breedlove actually served initially as “poetess laureate” when first appointed by Russell because Nevada’s first ever poet laureate was still alive at the time, according to research provided by the Nevada State Library and Archives.

“Literary Nevada,” edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and published by the University of Nevada Press in 2008, said Breedlove relied on friends and relatives to drive her around the state because she was legally blind. Breedlove spent her final years in Ferron, Utah, where she died at age 90.

The position of poet laureate does not exist in Nevada statute. The appointment form says the individual serves at the pleasure of the governor.

It seems controversy may be in the cards for the unpaid, honorary position.

Breedlove was succeeded by Norman Kaye in 1967. Kaye served until 2007, when then-Gov. Jim Gibbons named him poet laureate emeritus. The decision to change Kaye’s status so a new poet laureate could be selected generated some controversy for the Nevada Arts Council when it was first proposed in 2004. Kaye, a well-known pioneering Las Vegas lounge musician, objected to the change. Nevada does not currently have a poet laureate. Kaye died in 2012.

Nevada’s first poet laureate was L.B. “Tutor” Scherer, a flamboyant Las Vegan who had criminal ties and came to poetry late in life. He was named to the post by Russell in 1950.

Scherer was part of a mob syndicate in Los Angeles before heading to Las Vegas in the late 1930s or early 1940s. Scherer, along with others, began operating the Pioneer Club in 1942, among his many other business ventures.

He self-published “Reminiscing in Rhyme” in 1956 and died in 1957 of natural causes.

Contact Capital Bureau reporter Sean Whaley at swhaley@reviewjournal.com or 775-687-3900. Follow @seanw801 on Twitter.

Read Mildred Breedlove’s full poem, ‘Nevada’