City drops downtown tax plan, but still wants public subsidy for arena

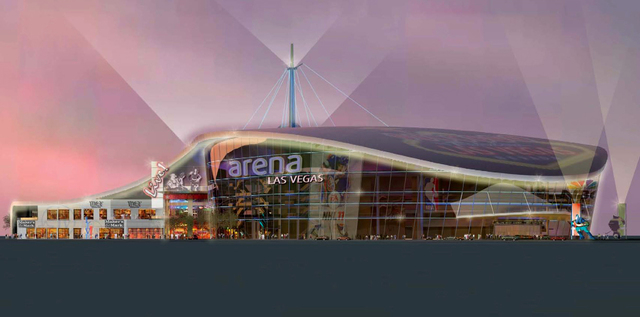

Las Vegas officials have abandoned a plan to tax downtown businesses to raise more than $50 million for a new sports arena but still want the $390 million development.

City officials have offered Baltimore-based developer Cordish Cos. more time to come up with a proposal for an arena that would include public financing.

The company’s 4-year-old exclusive negotiating agreement for a Symphony Park site is to expire by the end of the month unless the City Council votes to extend the deal until June.

With a vote scheduled today, the arena project’s backers spent Tuesday scrambling to make changes to appease opponents. The changes, however, only increased the gap between the approximately $150 million Cordish is pledging and the project’s estimated cost.

“It gives us an opportunity to figure out what that gap may be and what are some of the viable solutions to fill that gap,” City Manager Betsy Fretwell said.

Today’s vote is only to extend Cordish’s timeline to come up with a plan. It doesn’t guarantee any specific funding.

As late as Tuesday morning the city was projecting that Cordish would pay $151 million. City-backed bonds covered by arena revenue would generate another $187 million, and a controversial tax on downtown businesses would provide $52 million. The city would own the project, Fretwell said, making it a public asset but also meaning it wouldn’t be subject to property tax.

When asked in the afternoon about the downtown business tax through a special improvement district, city officials said that part of the proposal was off the table.

Cordish has said it could book 139 special events annually to pay for the project. And the company dangled the opportunity to attract professional basketball and hockey to Las Vegas as a possible added benefit.

Blake Cordish, a Cordish Cos. vice president, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal editorial board that arenas and stadiums were key contributors to successful downtown revivals in places such as Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

“They have been successful in acting as anchors for the revitalization of areas around them,” he said, adding that an arena could help generate new residential, retail and restaurant development near the proposed location on the southwest corner of Grand Central and City parkways.

Cordish’s original plan was to build the arena near the former city hall at Stewart Avenue and Las Vegas Boulevard. But in 2010 the company agreed to shift the site to Symphony Park because the city wanted to get Zappos to move into the old city hall. That deal included a $2.4 million incentive for Cordish.

Cordish said a proposal could have been done sooner, but the recession, the decision to exclude a casino from the project and shifting the site lengthened to the process. He said the requested extension doesn’t represent a missed deadline.

“I think it is really, frankly, unfair to say this has taken longer than is anticipated,” Cordish said.

He also said improvements to the overall economic landscape that make the project more feasible happened only recently.

“It has allowed both of us to come forward with concrete, major financial stakes in the ground,” Cordish said.

Mayor Carolyn Goodman, who joined Cordish and Fretwell at the Review-Journal, said the arena would give Las Vegas a chance to attract major league professional sports, a goal of hers and her husband, former Mayor Oscar Goodman.

“I know there has been a huge appetite for these professional teams,” Goodman said.

The plan’s public financing portion is meeting opposition from those who say a downtown sports arena should be privately funded and others are skeptical that the project’s business plan is feasible.

David Strow, a spokesman for Boyd Gaming Corp., the largest casino company downtown, said the company is “absolutely opposed” to any public financing for an arena.

“We are not opposed to building arenas; we just feel they should be privately financed,” Strow said.

Mayor Pro Tem Stavros Anthony also said if developers want to build an arena they should use private funding and private ownership.

“I don’t think the city should take the risk of owning an arena and I don’t think public funds should be used,” Anthony said, adding that he sees no reason to extend the Cordish agreement.

The risk of arena projects can be significant.

In Louisville, Ky., bond ratings agencies have downgraded public debt on the KFC Yum Center to junk status. Meanwhile, the arena-tracking website www.fieldofschemes.com reports the Sprint Center in Kansas City, Mo., generates an operating profit, but proceeds fall well short of the cost to repay construction debt. And the Miami Heat of the National Basketball Association is seeking to extend $6.5 million in operating subsidies it gets from hotel taxes for American Airlines Arena.

Others questioned whether a downtown arena would be economically viable in the competitive Southern Nevada marketplace.

Cordish officials said their studies so far haven’t factored in the impact of plans by MGM Resorts International and AEG to build a similarly sized, privately funded arena on the Strip.

The new MGM arena would join the MGM Grand Garden Arena, Mandalay Bay Events Center, the Thomas &Mack Center, Orleans Arena, the Colosseum at Caesars Palace and smaller competitors such as the Hard Rock Hotel in vying for paying events.

Pat Christensen of Las Vegas Events said a publicly subsidized arena downtown, in addition to MGM’s plan, would be “one venue too many.”

The problem, he said, is potential acts would play the venues against one another for higher guarantees.

“It would make it very difficult for both of them to be successful,” he said.

And the combination of gambling giant MGM Resorts and events company AEG would be stiff competition for a city venue, he said.

“MGM has established themselves as (having) the concert venues in town,” Christensen said. “If they build that new arena they will carry that with them.”