Developer finds thrill on Blue Diamond Hill

A bearded man walks across a plateau. He stops at the edge of a bluff and looks out at massive red-streaked cliffs.

He describes how this plateau could hold a town square with a main street, shops and a central park. Houses could fan out from there. And a school might be built.

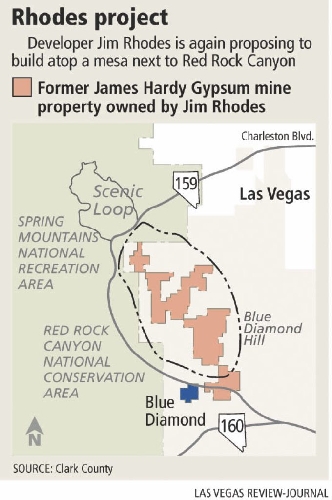

The enclave atop Blue Diamond Hill would be tucked behind nearby ridges and mesas, making it almost invisible from the floor of Red Rock National Conservation Area more than 1,000 feet below or anywhere else in the valley, said Ron Krater, a site planner hired by developer Jim Rhodes.

Krater and Rhodes representative Terry Murphy last month gave a tour of the 2,400-acre former mining site that is again at the heart of a public uproar.

The revitalized project is a clash between a developer who seeks a profitable venture and neighbors, conservationists and outdoor enthusiasts who want to preserve Red Rock's majestic scenery.

Rhodes hopes to sell million-dollar views near a regional gem that draws more than 1 million visitors a year.

Rhodes declined to be interviewed. But Krater said he has scrapped plans that stirred an outcry seven years ago, and now wants to work with the public to draft a plan everyone finds palatable.

"We'd like to demystify the process," said Krater, an urban designer based in California. "It's a thorough, thoughtful process, as opposed to the piecemeal approach that was used in the past."

Rhodes and Clark County officials, following a state Supreme Court ruling in his favor, struck a tentative deal that commissioners will review on April 21. Rhodes has agreed to drop a 5-year-old lawsuit that challenged a county code that forbids him from applying for any development near Red Rock denser than one house per two acres.

In return, he can apply for "major projects" that are at least 700 acres in size and have higher density than the zoning allows. The county would retain the right to reject any proposal.

Also, 700 acres abutting the conservation area would be left vacant.

The review for major projects is stringent and gives the county a lot of say about what gets developed, Krater said, emphasizing that the pact would not compel the county to accept any plan.

Still, the two sides probably would wrangle over density.

Rhodes initially sought to build 8,400 homes on Blue Diamond Hill, then reduced it in 2003 to 5,500 homes. Plans included a school, golf courses and businesses.

Krater said that instead of crafting a site plan and presenting it to the public, they will first talk with neighbors and other concerned people, then use their suggestions as much as possible.

But the dialogue must be constructive, Krater said. "If they say, 'No, no, no,' then that means they don't want anything."

Most residents of Blue Diamond, a small community, would prefer that Rhodes build nothing on the land, though they would settle for limiting him to the density that the current code allows. Almost 200 people trumpeted that sentiment at a March 31 advisory meeting.

"We don't want Red Rock Canyon to be part of the city; we want it to be apart from the city," said Heather Fisher, a Blue Diamond resident who launched Save Red Rock.com.

PROJECT HAS ITS CRITICS

One land-use consultant said he doubts Rhodes could pull off the project, given the heavy upfront cost and a real estate market that's not expected to recover for years.

"A very, very tough economic picture to justify this type of thing," said Jeff Rhoads, president of Argonaut Co. in Las Vegas.

He estimated the infrastructure alone would cost $30 million. That's on top of the $54 million the developer paid for the land, he said.

"Think of the millions of dollars you have to spend before you put up the first house," Rhoads said. "It's pretty dicey. It's hard to believe it makes sense."

Getting the needed financing will be even harder because of Jim Rhodes' credit problems, Rhoads said.

Rhodes filed for bankruptcy protection earlier this year and, according to one report, has about $400 million in liabilities.

One activist contends that Rhodes is trying to make the land more attractive so he can sell it at a higher price and pay off some of his debts.

"He's trying to create a perception of value so he can flip it," said Lisa Mayo DeRiso, whose group, Scenic Nevada, seeks to preserve pristine areas. "Can anybody really build houses up there and turn a profit?"

Murphy said Rhodes does not intend to sell the land. If he did sell it, the new owner would have to abide by any development agreement with the county, she said.

Also, Krater said developing the site won't be as costly as critics claim. That's partly because mining crews carved flat areas into Blue Diamond Hill and packed the dirt, making the land easier for Rhodes to develop than if he reshaped virgin hillsides.

As for utilities, a water pipeline runs along State Route 159, and the sewer hookups that serve neighboring Blue Diamond are within a few miles, he said. A pump station or two could pipe the water up the hill, and an on-site sewer plant could treat wastewater.

The site also has high wind and sun exposure, making it suitable for alternative energy, Krater said. The neighborhood might not become self-contained off the grid, but it probably could generate enough solar and wind energy to sell back to a power company, he said.

As part of the agreement, the main road would be built between the mesa's east side and Summerlin, rather than from State Route 159, to avoid causing traffic snarls in Red Rock Canyon, Krater said.

"We're very sensitive to the population and their way of life," he said.

But Rhoads, the land-use consultant, said building a thoroughfare from the east could be troublesome.

Depending on how it's aligned, the road would cross federal or county land, the Kern River gas line and land owned by the Howard Hughes Development Corp., he said.

The Bureau of Land Management would have to grant a right of way, Rhoads said. And private landowners might resist having a road stretch across their property.

A big hurdle would be building the road over Gypsum Ridge, which is more than 800 feet high in places, Rhoads said.

There's something else to consider, he said. A public road would give developers more leverage to pressure BLM into selling land around the thoroughfare. That could result in the urban corridor creeping west toward Red Rock, he said.

BLM might be more inclined to sell land with a public road because it would demand more policing than pure open space, Rhoads said. "When you open it to the public, it makes it harder for BLM to manage."

CHALLENGES OF THE MESA

DeRiso questioned whether it was possible to restore the value of a used-up mining site.

Krater, though, compared the mine-scarred land to a former tractor-testing site on which the Verrado planned community was built in Arizona.

One difference: Verrado was developed on flat land, not hilly terrain.

Krater said houses can be designed to blend into the landscape -- for instance, by requiring nonreflective roofs and limiting the colors to earth tones. Outdoor lighting can be curbed to reduce glare and avoid blurring the night sky.

Building one house per 2 acres is not optimal, either economically or visually, Krater said. By spreading out houses that much on a mesa, you're forced to build in the most visible spots, he said.

Better to cluster houses behind ridges, both to shroud the homes and create open areas that could be made available to the public, Krater said. People could hike up the hill and then relax in the park, he said.

Because there are underground mine shafts, extensive geological tests will be done to ensure the earth is stable, Krater said.

Rhodes' previous plans included a golf course, but that probably will be discarded, Krater said. "It doesn't seem environmentally responsible or economically feasible."

House prices haven't been set, but there will be a diverse mix, Murphy said, adding that teachers, bankers and doctors will live in the same neighborhood.

Mark Rink, an agent with Coldwell Banker, said the pricing would depend on the size of the lots, the view and other amenities.

At The Ridges, down the road in Summerlin, million-dollar homes are common, and Rhodes' site could be in that league, partly because it's close to Red Rock and not too far from the city, Rink said.

Even a townhouse probably would start at $300,000, and a custom home with a sweeping view could go for a million dollars-plus, Rink said.

Fledgling subdivisions also appeal to upscale buyers, he said. "People like the new stuff. It's trendy for the wealthy."

To draw buyers, Rhodes would have to strongly distinguish his homes from the other 40,000 vacant houses in the state, said Jeremy Aguero, a principal with Applied Analysis, an economic consulting firm in Las Vegas.

As with Coyote Springs, a large development planned northeast of Las Vegas, Rhodes must build utilities from the ground up, Aguero said. "It's incredibly expensive."

One difference is that Coyote Springs potentially could spread the costs over 100,000 homes, whereas Rhodes would have just a few thousand houses to absorb the costs, Aguero said.

Even with higher-end homes, Rhodes might have difficulty turning a healthy profit, he said.

PARKS AS BUFFERS

During his tour, Krater steered his SUV up a winding dirt road, the tires bouncing on the rugged terrain. He stopped on the summit.

From there you can see the Strip's cityscape to the east and Red Rock's towering mountains to the west.

A small portion of the homes would be built on the hilltop, Krater said.

He stepped onto a flat patch and talked of how it could be kept free of houses and turned into a small public park.

But Rhoads the planner was skeptical.

The project will be so expensive that the developer must do everything he can to profit, he said. That would mean offering the most stunning views to homebuyers and building houses where they could be seen from the valley.

"It's going to be hard not to put houses right on the edges to get those million-dollar prices," Rhoads said.

Krater reiterated that the county has the final say on what gets built. Computer simulations will illustrate how the development would look from any vantage point, including Red Rock, he said.

DeRiso, the Scenic Nevada activist, said many people don't trust Rhodes because of questionable financial and political dealings.

For instance, he hired former County Commissioner Erin Kenny as a consultant for $200,000 a year while she awaited trial on corruption and bribery charges, DeRiso said, citing news reports. Kenny was convicted and served about two years in federal prison.

Rhoads said the county gave developers a lot of leeway during the boom years. The county now must study potential impacts carefully and make sure a developer who is flirting with insolvency doesn't quit halfway through the project and leave a ghost town marring the hillside, he said.

"The checks and balances are only as good as the cop policing it."

Contact reporter Scott Wyland

at swyland@reviewjournal.com or 702-455-4519.