5,000 Clark County students headed to school without vaccinations

When Levi Cartwright starts eighth grade at Burkholder Middle School in Henderson on Aug. 13, he’ll be one of approximately 5,000 Clark County students who will return to class without having been vaccinated against at least one of 11 contagious and potentially dangerous diseases.

His mom, Christine, is unapologetic about her rejection of the immunization schedule recommended by the district and public health officials.

“I don’t want to damage my children for the risk of possibly coming in contact with something that may be out there,” she said, referring to persistent myths that vaccines can cause negative side effects in children. “It’s such a bigger risk than benefit for them.”

Of the more than 322,000 students enrolled in a Clark County school, about 1.5 percent will attend school this year without having been vaccinated. Their ability to do so is guaranteed by state law as long as their parents obtain an exemption from the district.

Parents are allowed to obtain exemptions for medical reasons or religious beliefs. In Clark County last year, up to 4,975 exemptions cited religious objections, while up to 532 were requested on medical grounds.

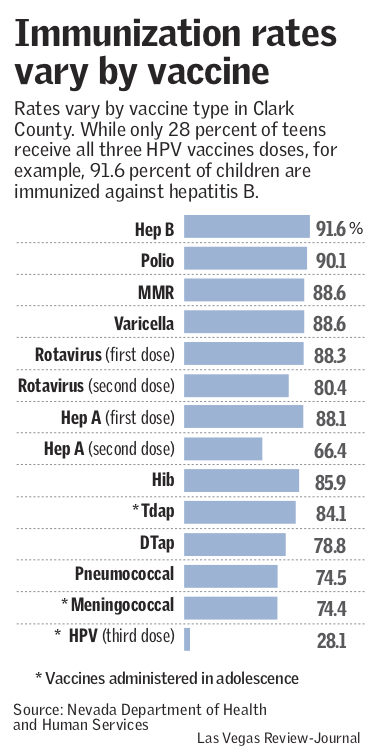

The exemptions are routinely granted without review when requested. Parents can opt out of vaccines individually, which is why immunization rates vary by vaccine.

The 1.5 percent exemption rate is an average of waivers obtained for seven vaccines and doesn’t include the quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine, which was newly required last year and therefore accounted for a small number of waivers.

Though unvaccinated individuals raise the risk of infection for the remainder of the student population, experts say the rate in Clark County schools is not high compared with that of some other districts and it is not near the threshold where it would trigger concerns about epidemics.

“That’s pretty low actually,” JoAnn Rupiper, chief nurse administrator at the Southern Nevada Health District, said of the school district’s rate.

But others note that the presence of even a small percentage of those without immunity can have deadly consequences for people with compromised immune systems.

“Someone who’s immunocompromised, they get the flu and they end up hospitalized and potentially die from the infection,” said Angela Berg, a pediatric nurse practitioner. “This entire section depends on others to not spread infection.”

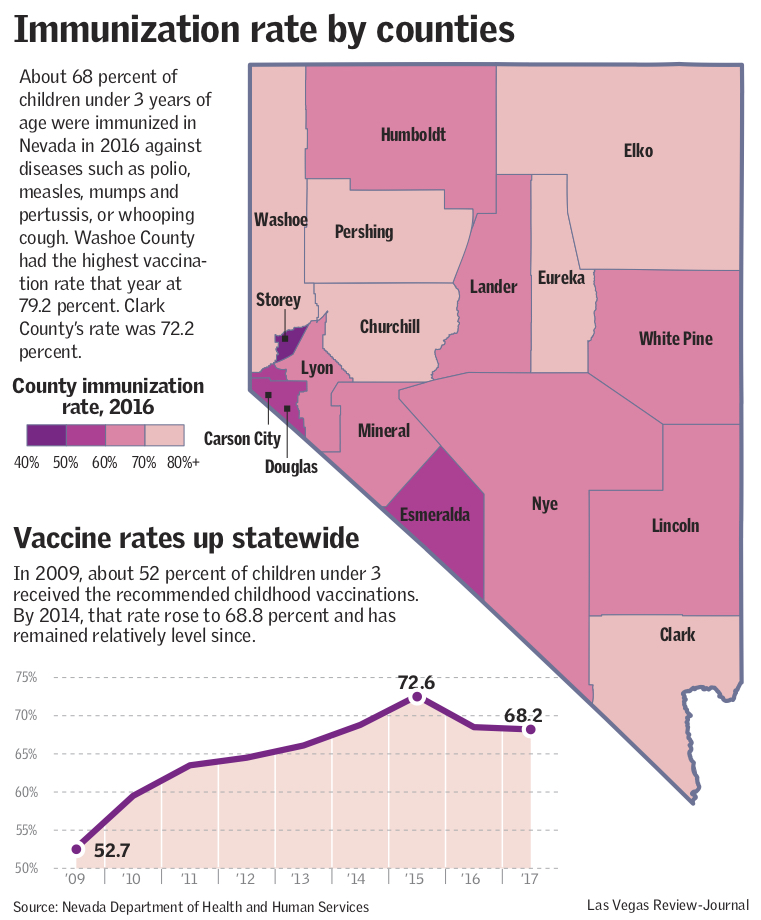

Lynn Row, the school district’s director of health services, said the immunization rate has been climbing steadily in recent years.

About 70.6 percent of Clark County children under 3 had received the recommended vaccines by that age in 2017, according to state data. That’s up from 51.8 percent in 2009.

“We’ve come a long way in the last five or six years in getting schools compliant,” Row said.

Autism myth lives on

Higher vaccination rates are important, because they lead to fewer cases of preventable diseases like measles and whooping cough, said Heidi Parker, executive director of Immunize Nevada, a nonprofit advocate for increasing vaccination rates.

Many diseases are now rare in the U.S. because of widespread vaccination. There were no cases of diphtheria or polio in the U.S. in 2016, for example, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Smallpox was officially declared a disease of the past by the World Health Assembly in May of 1980, making it the only disease that has been permanently eradicated thanks to widespread vaccination.

“We have a whole generation of patients now who haven’t seen these diseases, so they don’t realize how detrimental and life-threatening these diseases can be,” said Berg, who is also director of specialty services at the Children’s Specialty Center of Nevada. “(Yet) all of them are only a plane ride away.”

Misconceptions that vaccines are unsafe for children, fed by numerous authoritative-looking websites, have led some parents to decide their children are better off without their shots. Such reluctance has been blamed for a number of recent disease outbreaks nationwide, including a 2015 measles scare linked to Disney theme parks in Southern California.

A 1998 study published by Andrew Wakefield, a British doctor, used incomplete and fabricated data to link the immunization against measles, mumps and rubella to autism. Though the medical journal that published the study, the Lancet, retracted it in 2010 and Wakefield was removed from the U.K. medical register for unethical behavior, misconduct and fraud, the supposed autism link continues to persuade parents to forgo vaccination to this day.

Christine Cartwright said she learned of the theory when she took to the internet to research the possible pros and cons of vaccination.

“That alone was like, hmm. It got me concerned,” she said, adding that she hasn’t seen conclusive evidence that vaccines and autism aren’t linked.

Cartwright and other parents also worry that additives and preservatives in vaccines could harm their children.

Jacqui Hitter, a 34-year-old mother of two from Logandale, said she finds studies showing the additives don’t cause harm unpersuasive and noted that she is merely extending the natural-is-better philosophy she applies to her children’s diets.

“I don’t want to be injecting my children with all that stuff,” Hitter said.

Cartwright also cited the trace amounts of formaldehyde present in the vaccines as a reason for her rejection. It is used to kill vaccine contaminants and mostly removed before packaging, according to the CDC.

Formaldehyde also occurs naturally in the body and is found in everyday products like markers and cleaning supplies, Parker of Immunize Nevada said.

“I think sometimes things sound scary,” she said, adding, “If we don’t know, it becomes something we fear.”

Protecting the vulnerable

Instead of vaccinating their children, Cartwright and Hitter use natural methods, like vitamins and oils, to keep them healthy.

Supplements may help with general health, but they don’t protect against potentially deadly or life-altering diseases like measles or chicken pox, said Berg.

She recalled one child with leukemia who died from an infection before she could even begin treatment.

“To feel like you could lose the battle for their little life for something that could be prevented with a vaccine is really hard to swallow,” Berg said.

She works primarily with children who are undergoing treatment for cancer, blood disorders or rheumatic diseases. Because they’re often immunocompromised, those children can’t be vaccinated and thus rely on those around them to have that immunity.

Others, like grandparents with a weak immune system or people with allergies to a vaccine’s ingredients, rely on the general public’s immunity, too.

Parker said she’s not surprised parents hesitate to inject their children because of all the misinformation out there.

“I think the challenge is trying to find those credible sources,” she said. “Trying to wade through information online is hard.”

While some pediatricians will turn away parents and their children if they choose not to vaccinate — Cartwright said her children’s first doctor did that — Berg said it’s up to clinicians to create a “judgment-free zone” and provide parents with educational material to help them come to a final decision.

“I see it as our role as health care providers not to be frustrated,” Berg said. “I think that coming up with a reasonable compromise is certainly the goal that we should all have.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.

More information on vaccines

• Parents seeking information on vaccination can visit Immunize Nevada's FAQ page at https://immunizenevada.org/faqs.

• The CDC also compiles information for parents at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/common-faqs.htm.

• The Southern Nevada Health District offers immunizations. For more information, visit http://www.southernnevadahealthdistrict.org/immunizations/clinic-locations.php.

• The Cox Back to School Fair will also feature a low- to no-fee immunization clinic this year. The fair will be held at Downtown Summerlin, 1980 Festival Plaza Drive, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Aug. 12.