Amid math, English gains, Nevada students backslide on science tests

Nevada students might be doing better in English and math, but many find science perplexing.

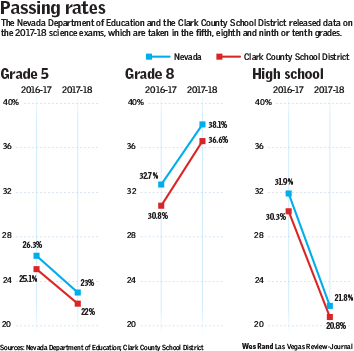

New data released Thursday by the Nevada Department of Education and the Clark County School District indicate that middle school students improved their science scores more than 5 percentage points on the state exam last spring, but elementary and high school results plummeted.

Nevada Department of Education spokesman Greg Bortolin noted that this is just the second year of testing reflecting a new, more demanding science exam, and the previous year’s numbers are considered baseline data.

“The state and districts are going to look at this, and they’re going to say, we need to do some work in fifth grade and we really need to look at what’s going on on this tenth-grade test,” he said. “I’m confident this will improve.”

Part of the eighth-grade success arises from the fact that students who took the test last year had three full years of science instruction aligned to the new standards on which they are tested, said Clark Count Assistant Superintendent Jesse Welsh.

“They were in sixth grade when these standards were implemented,” he said. “I would expect as teachers continue to develop proficiency in teaching to the new standards, we’d continue to see the results go up.”

Thursday’s release came two days after the state released new results for math and English exams, which saw improvement in almost every category year-to-year. Other data and updated ratings for all Nevada schools are expected next week.

Time and space

While obviously disappointed in the elementary and high school data, Welsh said the district is already looking for ways to improve.

In elementary school, for example, teachers have been focused on improving math and English language skills, meaning science often falls to the wayside. He said the district has been working on creating curricula that can cover multiple bases. For example, he said, teachers can have students read and analyze a science-based text.

“You can do it both at the same time, but you have to be consciously thinking along those lines,” he said.

At the high school level, the issues are slightly different, Welsh said. Previously, the high school science exam was only a “participation requirement,” meaning students were required to take the test, but passing wasn’t a requirement for graduation and scores weren’t factored into schools’ ratings.

Now, with science scores counting toward schools’ ratings, he expects there will be an increased focus on preparing for the exam.

Another issue will be trickier for some schools to handle. The science exam is given on a computer, and not all high schools have enough computers to test all their kids at once.

As a result, some schools had to start testing as early as February, when they were only halfway done teaching the science principles that could appear on the exam.

Science has historically always played second fiddle to English and math nationally, but changing economies will continue to push science to the forefront, Welsh said.

“For our kids to be successful and to have opportunities in many of the career fields that are out there, we need students that are going to be graduating with a solid science background,” he said. “And that doesn’t start in high school. That goes all the way back to elementary school.”

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.