More than 1 answer to how well Nevada funds education

Talk to just about anyone in Nevada and they’ll agree that the state’s public education system needs to improve.

But the unanimity ends there.

Superintendents and many education advocates have long called for the Legislature to put more money into schools.

“We need to get out of the ’60s and recognize the way that we fund students in this state is wrong,” Clark County School District Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky said in his September retirement announcement, attacking what he calls a chronic underfunding of public education.

But many legislators and other critics say they want evidence that the school districts are spending wisely and getting results before giving them more money.

“I think most people would agree with this: Something’s wrong; we should be doing better with what we have,” said David Gardner, a former legislator and current Clark County School Board candidate. “Until we figure out what that is, CCSD is going to have trouble getting more money.”

It’s a circular debate that has not led to significant improvement in the state’s educational standing.

In a three-part series beginning today, the Las Vegas Review-Journal will explore the state of school financing in Nevada and look at what needs to change to ensure that the state’s children can academically compete with counterparts from any other state.

Where we stand

Nevada’s quality of education consistently ranks at or near the bottom of national rankings. But the Silver State also underperforms by another measure: school funding. Education Week’s 2017 Quality Counts survey gave Nevada’s finances a D-minus.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the $8,275 per pupil spent by Nevada in fiscal year 2014 was less than the amount spent by all but five states: Mississippi, Oklahoma, Arizona, Idaho and Utah.

Nevada’s expenditures for primary and secondary education also are lower than the national average, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers. In fiscal 2017, that was 16.7 percent of all spending, compared with the national average of 19.4 percent.

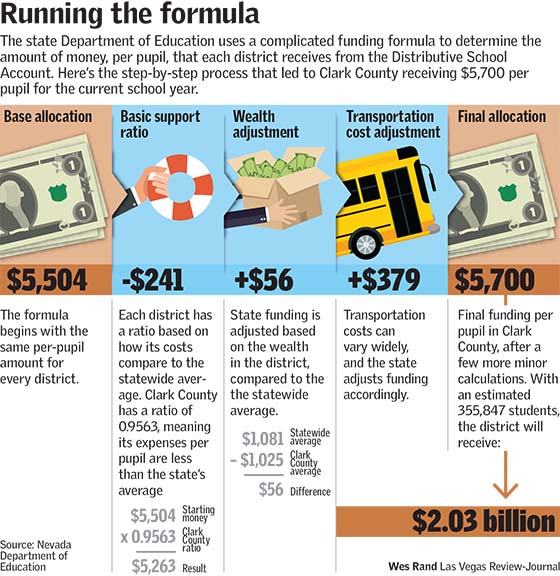

This year, the state allocated $2.8 billion for education, which was distributed according to a formula spelled out in the Nevada Plan, a blueprint designed to guarantee an equitable level of funding for school districts and charter schools.

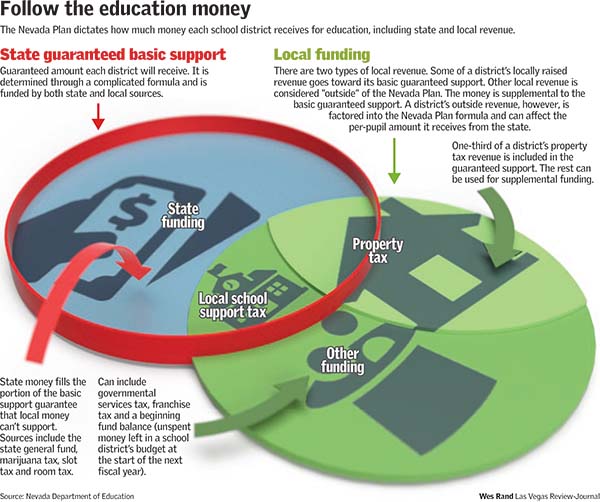

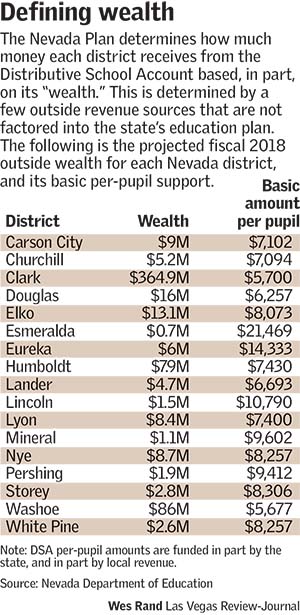

The Nevada Plan provides per-pupil funding for each of the 17 counties based primarily on three things: a county’s wealth, transportation costs and expenses. Each county has two main sources of revenue for its schools: money from the state’s Distributive School Account and local revenue.

To equalize spending, the state subtracts money from districts that have more local wealth and revenue. The amount that’s left is what superintendents call “the base.”

Superintendents and other critics argue that the base is simply not enough to educate the state’s 473,000 students, the majority of whom are in Clark County.

“One of the concerns I have with the funding formula is it hasn’t kept up with inflationary costs,” said Dave Jensen, the Humboldt County School District superintendent. “We do need to make a concerted effort to increase the per-pupil allocation through the DSA formula.”

The superintendents also would like the Nevada Plan’s distribution formula itself to be updated to reflect the state’s more diverse student population, which includes more English-language learners who often require remedial work to catch up to their peers.

But they are hesitant to suggest big changes to the formula now, because doing so without increasing funding would reward some districts at the expense of others.

“We, as 17 superintendents, have agreed over the course of time that we have to continue to fund the base,” said Dale Norton, superintendent of the Nye County School District.

The case for Clark County

In the Clark County School District, which is grappling with a budget deficit most recently estimated at over $60 million, there are other concerns.

Certain revenue raised almost exclusively in the county — such as slot, room and marijuana taxes — doesn’t go to the school district. Instead, it is sent to the Distributive School Account and redistributed statewide.

“It means that money that is created in Southern Nevada, that is generated in Southern Nevada, is sent to the state and … ends up going out to other counties instead of the county that it was generated in,” Skorkowsky said.

Critics also note that the portion of those taxes designated for education does not translate to additional funding for schools. Instead, that money is deducted from revenue placed in the DSA from the state general fund.

Case in point: Over $477 million originally slated for the schools was returned to the state’s general fund since fiscal 2000. That’s in part because revenue from other sources such as room and slot taxes came in higher than projected.

Some superintendents, including Skorkowsky, say the districts should benefit from that money, noting that some of those taxes were “sold” to the public as a revenue stream for education.

The Legislature has increased education funding in recent years, spurred on by Gov. Brian Sandoval. That includes funneling over $100 million for the Victory and Zoom programs, which provide more money for English-language learners and students in poverty.

Although Skorkowsky lauds those efforts, he says more needs to be done. The base, he argued, is chronically underfunded.

Lack of trust

Part of the problem is that two sides have been fighting over education funding for so long that it makes it harder to find common ground.

“We’re operating in a really low-trust environment, and that’s why Clark County’s driven into the position that it’s in now,” said Nancy Brune, executive director of the nonprofit Kenny Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, referencing the Clark County School District’s current funding issues.

Legislators and stakeholders don’t trust the district to spend possible additional money in a way that will produce a return on investment, she said.

That’s likely why recent increases in education funding have primarily been categorical, used only for a certain purpose, like the Zoom and Victory funds, Brune said.

Similarly, state Superintendent of Public Instruction Steve Canavero said the education system must show it can produce results before it can ask for an increase in base funding.

“There’s a level of trust that we’re building in the state,” he said. “I think the more that we can do as an education system to increase transparency and demonstrate results and changes that we’re making to correspond to our end of the bargain, the more likely it is that we can win favor.”

Gardner said he hopes the reorganization of the Clark County School District could help the district make its case for more funding by improving its performance. Gardner sponsored the legislation that mandated the reorganization in 2015, when he was an assemblyman.

In search of a fair comparison

He wants Nevada to improve enough to compete with states like Arizona and Utah, which have somewhat similar demographics and perform better while spending less per student, $7,457 and $6,546, respectively, versus Nevada’s $8,275.

Those are common comparisons, said Mike Griffith, a school finance specialist at the Education Commission for the States, based in Denver. But they’re not necessarily fair ones.

“It’s hard when you compare two states because of the demographics, the cost structure and their goals,” he said.

In Utah, for example, only 37 percent of students qualify for free and reduced-cost lunch, a measure of poverty. The national average is 52 percent. In Nevada, it’s 53 percent.

Nevada also has one of the highest percentages of students who are English-language learners. At 16 percent, it is second only to California. The national average is about 9.3 percent; Utah is at around 6 percent.

Statistics like those argue that Nevada should devote more resources to education if it is to remain nationally competitive.

“These are things that drive education costs,” Griffith said.

Next in the series: a historical look at education funding in the Silver State — and where Nevada has succeeded and failed.

Contact Meghin Delaney at mdelaney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281. Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-483-4630. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.