Study shows Nevada schools have largest average class sizes

Denise Lovern wants you to imagine your living room. Start with it empty.

Then add a counter or two, maybe a sink, some built-in shelves and a teacher-sized desk and chair. The space probably still feels roomy.

Now, add 36 smaller desks and chairs and children to sit in them. The kids are 9 and 10, so they’re not big. Still, there are almost 40 of them.

The room doesn’t feel so comfortable anymore, does it? In fact, it feels downright cramped.

For Lovern, 57, a 28-year veteran teacher in the Clark County School District, this is her day-to-day reality at Steele

Elementary School in Las Vegas. And she says it interferes with her ability to do her job and ultimately penalizes the kids.

“Nevada’s children deserve smaller class sizes. We need to stop setting up our kids for failure,” she said.

Class size is a national issue, with parents and educators generally taking the view that smaller is better, as that affords students more one-on-one attention and provides a more reasonable workload for teachers. But research is mixed, and skeptics wonder whether the extraordinary expense required to reach “optimal” class sizes — whatever that might be — would be worth the achievement gains that might be realized.

Nevada is at the forefront of the debate, after a study by the National Education Association found that the state had the largest average class sizes in the nation last year for the second year running, followed by Arizona and Utah.

Deficits add to pressure

And despite a 27-year-old state law to reduce class sizes, the group’s data show that Nevada classrooms have added an average of seven students over the past three years.

In Clark County, the issue predates the school district’s recent budget problems, but two successive deficits topping $60 million haven’t helped.

When Clark County principals and schools were forced to make additional budget cuts in May, they warned that classes would grow, with some high school classes topping 50 students.

Parents will find out what that means for their kids when more than 320,000 students return to 360 Clark County schools Monday for the start of the 2018-19 year.

Class sizes can vary widely in Clark County depending on the school and the grade level.

Lovern, for example, taught 36 fourth-graders in 2016-17 in a portable, one of the overflow rooms set up on overenrolled campuses. But last year, she had 20 second-graders in a big room built to hold a fifth-grade class. It made a huge difference, she said.

“I was able to kill it. I loved it,” she said of her smaller class. “I felt there were serious strides made. The year before with 36, not so much. There’s a lot of teachers that burn out doing it.”

This year, she’ll teach third grade and is expecting 26 kids on the first day.

New Superintendent Jesus Jara has said reducing class sizes is critical, and he instructed his deputy superintendent to work with associate superintendents to ensure that teachers are fully utilized and that students are more evenly distributed.

“Having class sizes where (teachers are) in a manageable space with students is critical,” he told one group of parents in July.

State laws and incentives

Under state law, kindergarten classes should have a 16-to-1 ratio of students to teachers, rising to 17-to-1 in the second grade and 20-to-1 in the third grade. The 1991 law, which has been updated by the Legislature a few times since, doesn’t prescribe class sizes for any other grades.

Some state funding, about $147.4 million statewide for the 2017-18 year, is allocated to districts to help them comply, but there’s no enforcement mechanism when they don’t reach the targets.

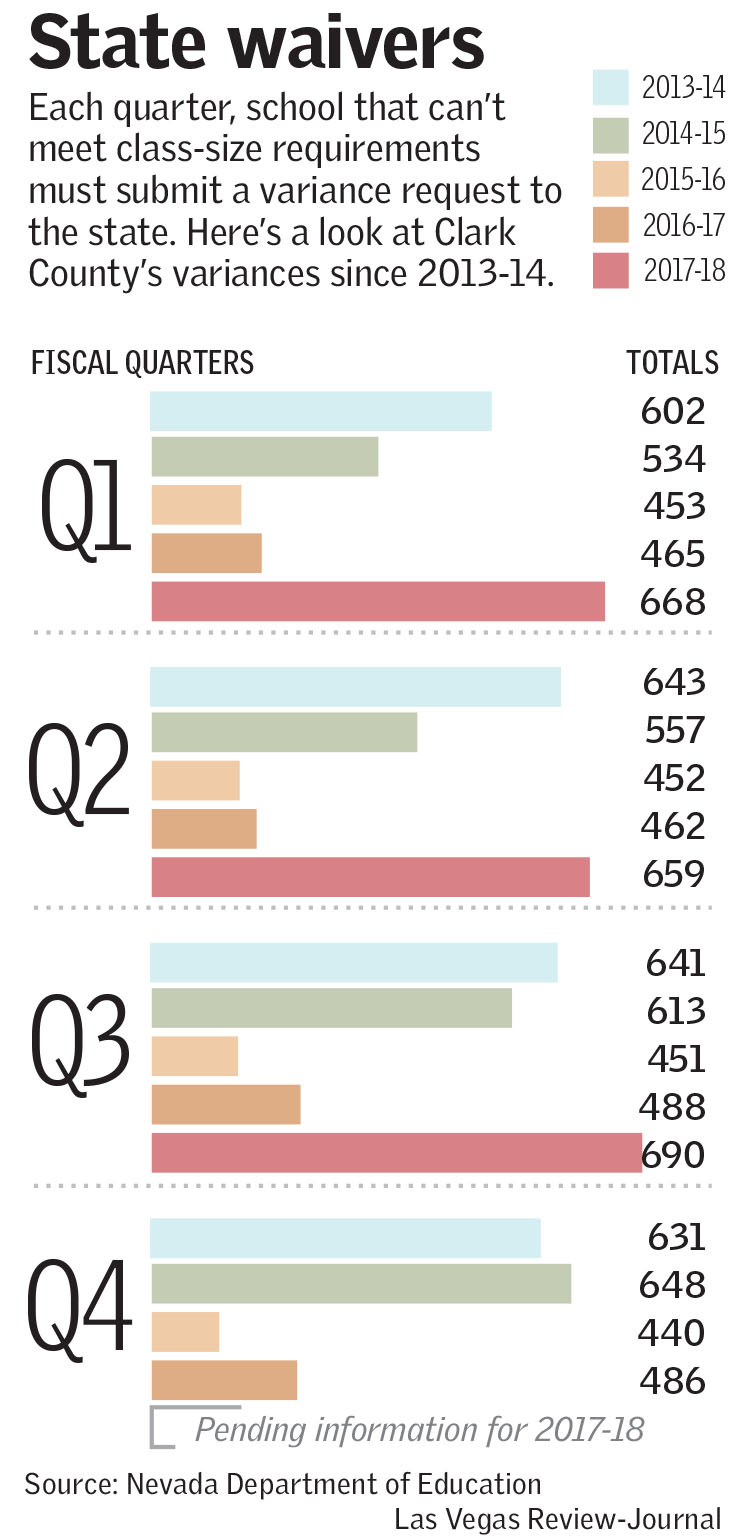

If a grade level in a school will exceed the ratios, districts simply apply for a variance with the state. The schools must check a box stating why they are applying for the variance. In many cases, districts cite financial reasons, but lack of space and inability to hire a qualified teacher also are sometimes cited.

The variances, which are routinely approved, are collected and presented to the state Board of Education on a quarterly basis.

State data show that the number of variance requests has generally increased year over year, but it doesn’t indicate whether classes are falling further out of compliance. That’s partly because the state law prescribing ratios has changed since the state began tracking data, said Meghan Hanke, an analyst for the state Department of Education.

In practice

Each year, freshman English teacher Jessica Maleskey teaches about 200 students over six periods at Liberty High School in Henderson. Maleskey, a 29-year-old Clark County graduate, will start her seventh year as a teacher on Monday.

She has 46 desks in her classroom. Right now, they’re neatly arranged two by two, but that changes once you add student bodies to the arrangement

She doesn’t teach 46 kids each period; some classes have as few as 34. But ideally she’d have no more than 20 kids.

“Students need one-on-one attention,” she said.

Maleskey said she has a supportive administration and English department at the school, which helps reduce the burden. She’s had a student teacher most years, which allows her to work individually with students with another adult to keep an eye on the room and answer questions.

She believes that class sizes would be smaller if lawmakers saw what working conditions were like.

“They need to be in our schools to see what’s happening. They don’t see this,” she said.

Lovern agrees and says it’s time for parents and teachers to get more involved in the legislative process. She wants the state’s funding formula to be revamped, and she wants it done quickly.

“As far as parents and community, contact your legislators, contact your governor, contact everyone who is involved in this decision-making process,” she said.

That’s what Natalie Carter is hoping for, too.

A 47-year-old mother of three and English composition professor at UNLV, she notes that her classes are limited to no more than 25 students. It’s insane to her that her two children still in Clark County schools, one who will start 11th grade at Silverado High School and one who enters seventh grade at Schofield Middle School, are in classrooms twice that size.

“This is what our life is,” she said. “We will have overcrowded classrooms until there’s a huge overhaul. I’m not sure of the answer to what we can do to change, but the step of having parents become more involved is huge.”

Not a panacea

It’s not clear how much money it would take to bring Nevada into compliance with state law.

There’s also no clear evidence that cutting class sizes would fix the ills of the state’s education system, said Nancy Brune, the executive director of the Guinn Center for Policy Priorities.

Brune has reviewed studies on class size initiatives. It’s a mixed bag. There isn’t research out there that says if you make incremental changes — for example, going from 40 to 35 kids — it’ll produce a return on investment, she said.

“Given then it’s very expensive and the ROI is pretty small, you could argue there are other programs that would have a bigger ROI,” Brune said. “If funds are constrained, you may want to think about investing in other programs, like (pre-kindergarten programs).”

Most research suggests that having an effective educator in front of kids, no matter the class size, produces better results, and Brune said that may be an area the Legislature should consider.

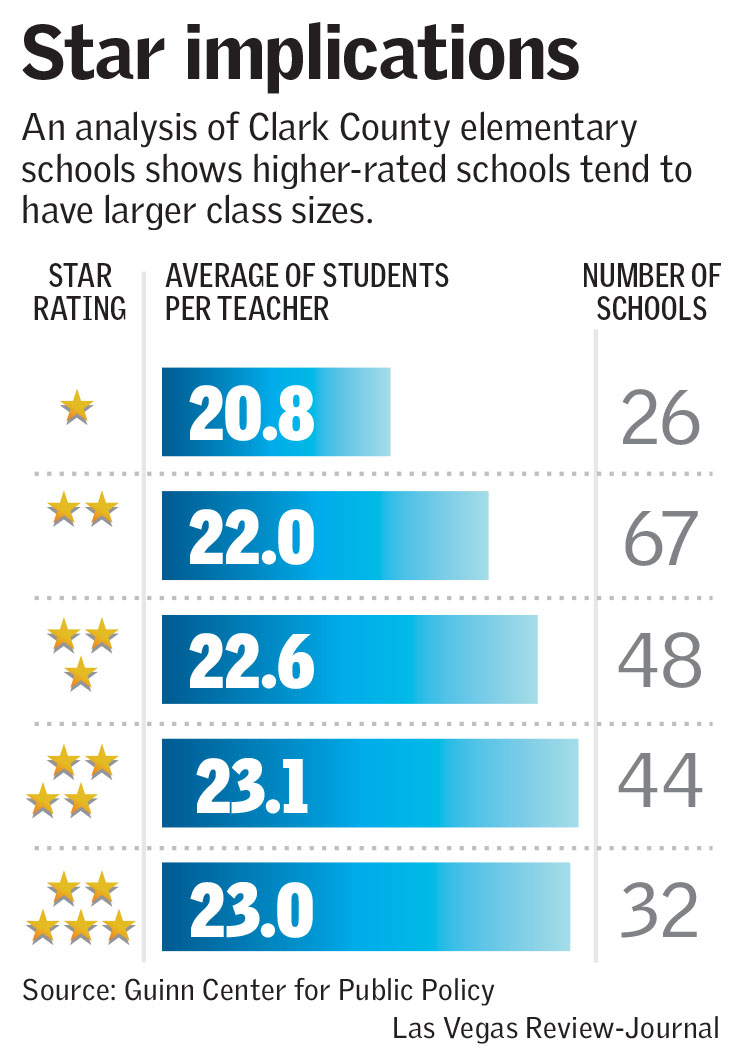

Brune put together an analysis of student-teacher ratios compared with the state-issued star ratings for schools in Clark County, and her analysis shows that schools with a higher star rating actually have higher average class sizes.

That doesn’t mean that larger classroom sizes lead to improved student outcomes, she cautioned.

“This does suggest, again, that outcomes may not be directly tied to the class size but to the person in the classroom or the instructional materials they are using,” she said. “Since it matters who is in the classroom, maybe we should be focusing on promoting or moving really effective teachers.”

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.

Stricter targets

New recommendations made to the Nevada state Board of Education in July say class sizes should be smaller than those already prescribed by in law, with a 15-to-1 ratio for grades three and under and all other grades at 25-to-1.

The recommendations grew out of a law passed in 2017 spearheaded by Assemblywoman Brittney Miller, D-Las Vegas. Miller, a sixth-grade English teacher at Canarelli Middle School in Las Vegas who is in her eighth year in the classroom. She said has never had what she considers a small class.

For some, the new recommendations are wishful thinking unless they come with additional money.

"Approving this (recommendation) doesn't magically staff school(s) at this level," state board member Mark Newburn noted at the July meeting.