Ernest Becker

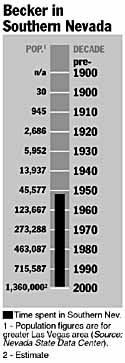

Howard Hughes was not famous for providing inside tips to fellow entrepreneurs. He did it at least once, though it wasn't intentional. In the late 1940s, Hughes' personal secretary told her husband, Jay Sims, that the eccentric billionaire was quietly planning to move Hughes Aircraft from Southern California to the west side of the Las Vegas Valley. Sims, in turn, passed the tip to his business partner, a young Southern California home builder named Ernie Becker, and urged him to buy all the land he could in the area of West Charleston.

"He took the advice," says Barry, the second of Becker's four sons. "So they came up and bought the original 250 acres that is Charleston Heights."

In so doing, Ernest A. Becker III initiated and expedited development of the western half of the Las Vegas Valley, which continues to this day. His story is told here through his four sons, because their father, at the time of this writing, was recovering from an accident and could not be interviewed.

Hughes had traded 73,000 acres of land he owned in five Northern Nevada counties for 25,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management property near the base of the Spring Mountains. He told the BLM he wanted to develop "guided-missile devices."

Becker moved to Las Vegas, but Hughes didn't, mainly because his top scientists, technicians and executives let him know they had no intention of being shipped out into the wastes of Nevada. But Hughes kept the land.

With or without Hughes, Becker sized up Las Vegas as a winning proposition. The Nevada Test Site was being established and an entire new workforce was moving to town. The Korean War was under way, the Air Force base had been re-opened, and GIs were moving into the area. Las Vegas was short of everything, especially houses.

"At the time Charleston Boulevard was paved as far as Highland Avenue," eldest son Ernest IV recalls. Charleston also was the only one of Las Vegas' main thoroughfares that reached all the way to the Spring Mountains and Red Rock.

In the postwar years, the development pattern of Las Vegas had tended eastward and southward into Paradise Valley. On the west side of the railroad tracks, there was very little civilization.

Becker's first tract was at the corner of Alta Drive and Falcon Way, just west of Decatur Boulevard. Becker called his community "Charleston Heights."

In the fall of 1952, Becker announced plans to build what was, up until that time, the largest residential development in the region, 1,400 homes. At the same time, he began to develop Decatur Boulevard as a commercial strip, and to acquire more land farther west, as far as Rainbow Boulevard, which would be developed in the 1960s and '70s.

The first problem was water. No city lines reached that far west.

"He had to drill his own wells and he had to form his own water company, which he called the Charleston Heights Water Company," says Ernest IV.

A few years later, Becker was in a fight with the newly created Las Vegas Valley Water District, which claimed that small private wells were drawing down the valley's water supply. State Engineer Hugh Shamberger ordered Becker to shut down his three wells and hook up to the LVVWD system. Becker appealed, claiming the cost of the water system modifications would be too expensive.

The give-and-take continued until August of 1965, when Becker sold his wells and distribution system to the district for $438,000.

Ernest August Becker III was the grandson of a successful land speculator of the same name, who moved to Southern California and went into business in 1903. Ernest I dealt in undeveloped land parcels, and the family created the Los Angeles suburb of Eagle Rock. Ernest A. Becker II was the family's first real builder, constructing homes and real estate all over the Southern California.

Ernest III built his first housing tract by the time he was a junior at the University of Southern California, which he attended from 1938 to 1940, distinguishing himself on the Trojan football team.

In 1941, the Beckers became part of one of Southern California's most famous pioneer families when Ernest III married Betty Weddington. Grandfather Weddington had been the first sheriff in the San Fernando Valley, and his family founded the Los Angeles suburb that became North Hollywood.

Discharged from the U.S. Coast Guard in 1945, Ernie III resumed residential construction.

But young Becker found the postwar Southern California bureaucracy to be a pain.

Nowhere was the housing market hotter than in Las Vegas. Becker's homes sold even while they were just artists' sketches on paper. The first homes sold for under $10,000.

"He really couldn't keep up with the demand," says Ernest IV, "so he would go into joint ventures or subdivide lots to keep up with it."

"There are about 63 subdivisions under the Charleston Heights name that he developed, but we were at our height in the 1960s, turning out developed lots, about 3,000 of them a year, for Sproul Homes."

The combined house output of Becker homes, including the various partnerships into which they entered, is probably in excess of 10,000, by his estimates, and at at one time in the 1960s, Sproul alone was turning out 27 houses a week.

"We didn't build that much in the '80s, and we quit building houses in 1984," says Ernest IV. "In the past five years, we have developed three or four thousand lots over in the vicinity of Cheyenne (Avenue) and MLK Boulevard."

Ernest IV explains that his dad learned from experience that the most profitable and least troublesome way of building new neighborhoods is to develop lots, sell them to other home builders, then erect and run the shopping centers needed by the new residents. The nucleus of the commercial district established by Becker in the early 1960s was the Charleston Heights Shopping Center at Decatur and Alta. It boasted a Safeway Supermarket, Walgreen's Drugs, Grant's Department Store and numerous smaller shops, including a tavern with slot machines. In 1963, just south of the shopping center, Becker built the one business essential to any respectable middle-class 1960s neighborhood -- a bowling alley. It had 36 lanes. And slot machines.

The family sometimes sold the commercial buildings, and sometimes they kept them and leased them. But in all cases, if there were slot machines on the premises, they were owned by the family.

In 1974, says Ernest IV, the family established a slot-route company called Sunset Coin to service their own machines, and began to enjoy the fruits of an entirely new enterprise -- gaming. As the number of Becker-built shopping centers increased, so did the size of Sunset Coin.

Becker's sons, Ernest, Barry, Randall and Bruce would join him at Las Vegas job sites while they still in high school, spending their summers framing houses, digging ditches and busting up caliche with picks.

"It was part of the indoctrination into the business," says Barry. "We used to work from sunup to sundown, and we did virtually everything. We had a significant amount of experience before we went to work full time. If you can call us executives, we're working executives."

As working executives, the Becker boys later would expand the scope of the family business. Each found a niche. Ernest IV came up from Los Angeles in 1962, right out of high school. Today, he is in charge of construction. Barry came in 1970, and became involved in the buying and selling of real estate. Bruce came in 1971 and was put in charge of running Charleston Heights Bowl. As it happened, the youngest son had the grandest idea.

One day at a family meeting, Ernest IV recalls, Bruce announced that he would like to build a hotel-casino onto the bowling alley.

"Since the casinos are adding bowling alleys to their casinos, I want to add a casino to my bowling alley," Bruce joked to reporters when the project was announced.

A proud family, they wanted to name the place in honor of one of their forebears. Presumably, "Ernie's" or "Becker's" lacked the needed pizazz.

They settled on a colorful but distant relative, "Arizona" Charlie Meadows. According to family lore, Meadows had been a sharpshooter in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. In fact, the only known picture of him shows a man dressed a lot like Buffalo Bill, with buckskins, hat cocked at a jaunty angle, and a dapper Van Dyke beard. After leaving the show, he went north and supposedly struck it rich in the Yukon, then lost his mine in a poker game. He then opened "The Grand Palace" a saloon and dance hall in Dawson City.

The old sharpshooter almost certainly had an easier time opening The Grand Palace than Bruce Becker had getting approval to open Arizona Charlie's on the site of the old Charleston Heights Bowl.

It was to be a "neighborhood" hotel-casino. Most were a few blocks off the Strip or Fremont Street. And some lined the Boulder Highway as they had since the time of Hoover Dam's construction.

Predictably, when plans for the resort were announced in early 1987, a howl of protest arose from nearby residents. Too much traffic, too many drunks, they complained. The hotel would overload the sewer system, some posited. Others predicted that property values would tumble, though local real estate agents predicted the exact opposite.

The $18 million resort opened in April 1988. In 1994, it underwent a $40 million expansion, and the bowling alley went into the gutter to make way for a larger casino.

A failed attempt to expand into the Missouri riverboat gaming market in the early 1990s pushed the otherwise successful Arizona Charlie's into bankruptcy. The venture was backed by some $40 million in bonds, and when Missouri regulators refused Bruce Becker's licensing application, over half the bonds were purchased at fire-sale prices by corporate raider Carl Icahn who, at this writing, is supervising operations of the company.

An outgoing and personable man, active in the state and local Republican party, Becker III always was generous with contributions to favored candidates, and gave deep discounts to the GOP when it needed to rent commercial space for campaign headquarters. But he never sought elected office.

He was quite active in the National Association of Homebuilders. He first elected vice president, then president of the huge organization in 1978.

The result was that in 1979, 1980 and 1981, the NAHB held its convention in Las Vegas.

Ernie III's favorite cause probably was college athletics. For most of his life, he has sported the flat-top crew cut he wore on the USC gridiron. He donated 40 acres of land each to USC and UNLV, and served on the UNLV Academic Foundation. He also served on the committees that brought football coach Ron Meyer, as well as basketball coach Jerry Tarkanian, to UNLV.

When schools had to be built in a new Becker neighborhood, the land was donated by the Beckers. When a church needed some land, the congregation asked Ernie. Parks are part of a complete neighborhood, and Ernie Becker donated the land. He also gave land to youth groups.

Together with the Collins Brothers, the Beckers purchased a large plot of land in North Las Vegas that included the 1860s-era Kiel Ranch. Coincidentally, it had been a favorite retreat for Ernie III's grandmother, who suffered from asthma, and found relief in the desert. Concerned about the deteriorating condition of the place, the partners donated the ranch to the city of North Las Vegas, hopeful that it would be restored for the local bicentennial celebration in 1976.

North Las Vegas leaders couldn't decide what to do with the ranch. While they deliberated, the ranch's landmark "White House," the Park Mansion, burned down. The city is currently working to restore the property.

Ernest Becker III has been a wealthy man for a very long time and certainly could have embarked upon any business venture that struck his fancy. But building homes was always his first love.

"Home building is exciting," he said in a 1988 interview. "There's no place a person spends more time in his life than in his home. When you have a nice house and you drive down the street and turn into your driveway, you feel excited. You raise your kids there. You live your life there. That feeling doesn't happen with a car or a boat. I can't imagine doing anything else."

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full