Flooding dissolves dreams

FERNLEY -- Esther Levine's eyes fill with tears as she wanders through the naked shell of what had once been her dream home.

She listens dejectedly as a building inspector declares she must remove more drywall from the walls, points out mold developing on studs and suggests they pull up floorboards to determine if water damaged the foundation.

"I am terrified," Levine says.

Levine, her daughter, two grandchildren and their pets escaped with their lives and nothing else when a foot of water flowed into their home after a levee broke at the dirt-bank irrigation canal that runs along the southern edge of Fernley, about 30 miles east of Reno.

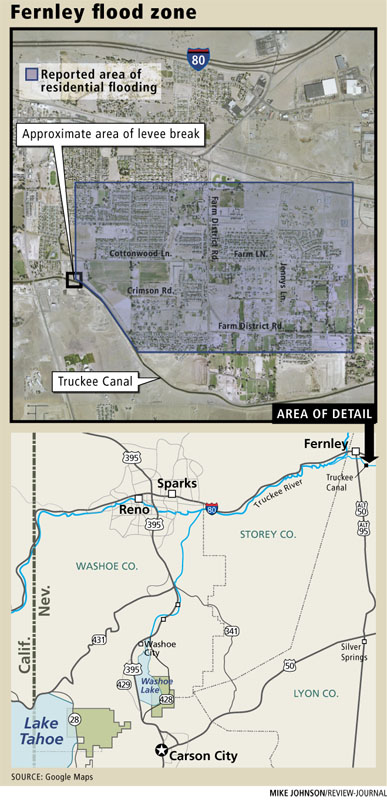

A 50-foot section of the Truckee Canal ruptured at 4:16 a.m. on Jan. 5 after a 2-inch rainstorm in the normally arid city of 20,000 on Interstate 80.

Primary flooding occurred in a low-lying, 2-square-mile area more than two miles from the rupture point.

Floodwaters have receded here in Fernley. What remains is a lot of mud and lost dreams.

The blame game has begun.

Four days after the flood, Reno lawyer Robert Hager filed the first lawsuit against the city, subdivision developers and the canal operator, the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District.

The irrigation district is a state-approved political subdivision made up of farmers and other water right holders in Lyon and Churchill counties.

Several other firms have followed with their own lawsuits.

Hager has added two more clients and set up a Web site seeking others to join in a class-action lawsuit for an undetermined amount of money.

He expects even farmers who receive water from the canal will join the lawsuit this spring when they find they can't irrigate their fields.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which owns and originally built the Truckee Canal, won't let any water flow until its team of forensic analysts devises a permanent solution that guarantees the safety of Fernley residents.

That solution could include lining the 32-mile-long canal with concrete, according to Bureau of Reclamation spokesman Jeffrey McCracken. That step probably would require an infusion of funds from Congress.

McCracken noted that most canals around the country are made of dirt. Only now are contractors replacing dirt with concrete at the All American Canal, which carries water from the Colorado River to farms in Southern California's Imperial Valley.

Six times before the Jan. 5 break, the Truckee Canal levee was breached. The most recent breach was in December 1996 about a mile from the latest rupture. The 1996 rupture flooded 60 homes but clearly did not stop the subdividing of Fernley, where the population has more than doubled since it became a city in 2001.

City Manager Gary Bacock said virtually all of the 590 homes that experienced flood damage on Jan. 5 were constructed after the last flood.

In his view, it remains to be seen whether the flooding will halt Fernley's growth.

Bacock takes a laser pointer and shows on a map in his office the locations of other approved but as yet undeveloped neighborhoods.

They are far closer to the rupture point than Levine's neighborhood. The city already had built streets and brought sewer and water facilities to these developments.

"We are going to have to replace those streets," he said.

Bacock said he is confident the Bureau of Reclamation will come up with a permanent solution to prevent future breaks in the canal and ensure public safety.

"It is not gloom and doom here," he said. "We are very positive about our future."

Irrigation district operations manager David Overvold said his agency never advised the city of Fernley to stop development along the canal after the 1996 breach.

What it did was ask that developers dump more dirt along the banks of the canal, he said.

Both Bacock and Overvold are reluctant to talk about litigation. Under state law, their individual liability for damages is limited to $75,000 per home.

"That is a matter that will be decided by the judicial system," Bacock said.

Bacock prefers talking about how the breach affected only 8 percent of the 7,500 homes in his city and how most residents affected by the flooding quickly took steps to recover.

"I don't see people standing around waiting for someone else to come and help them," he said. "The attitude they have is, 'I want to get back to normal as fast as I can.'"

Overvold said he has not heard anyone demand that the canal should be closed permanently. He fully expects to have water flowing into farmland this spring.

A few miles down U.S. Highway 95, the 50-resident town of Hazen and its fire department depends on the canal; if the water isn't flowing, the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District will have to truck it to them, Overvold said.

The history of water in the region goes back to the early 1900s. The Derby Dam was built along the Truckee, just west of Fernley, as part of the federal Newlands Project to divert water, create farms in the Nevada high desert and generate power at Lahontan Dam east of Fallon.

Before 1967, there were no restrictions on diversions from Derby Dam into the Truckee Canal. But the elevation of nearby Pyramid Lake fell by 80 feet, and the lack of water flowing into the lake prevented spawning by the native cui-ui fish.

After years of litigation over restoring the endangered fish, new operating criteria were implemented.

Now, most farms in the Newlands Project are irrigated by Carson River water that originates high in California's Sierra Nevada and flows into the reservoir behind Lahontan Dam. Just 5,000 acres of the 60,000 acres irrigated through the project comes from the Truckee River diversion.

Hager has five experts probing soil along 104-year-old Truckee Canal in a quest to determine a cause for the breach.

They aren't alone. Last week, more than a dozen Bureau of Reclamation and irrigation district employees were digging into soils near the breach point.

"I am just digging out muck, and the trucks are taking it to the other side" of the bank, crane operator Leo Barkull said.

From what his analysts have turned up, Hager believes the irrigation district rarely cleaned out the canal at the breach point.

"The silt at the bottom shows it was not properly maintained," he said.

"We have found silt seven feet deep. One hundred years of deposits of silt raised the water level and greatly reduced the capacity of the canal to carry water."

The Bureau of Reclamation also bears responsibility for the damage, Hager said.

Although the federal agency turned over the authority of managing and maintaining the canal to the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District in 1926, the agency still has the responsibility to ensure the canal is properly maintained, Hager said.

"It is their canal," he said.

From what he has discovered, Hager said, the bottom of the 50-foot-wide canal originally was at least 3 feet below the elevation of adjacent fields.

Like others in her neighborhood far from the canal, Levine never realized there was any danger of flooding when she bought her home in 2005.

"I didn't even know there was a dike here," she said. "Nobody told us we needed flood insurance."

Water from the breach ran through adjacent farm fields, then through acre-lot neighborhoods and undeveloped subdivisions before settling in the lowest ground in the Shadow Mountain-Jennys Lane neighborhood.

Bacock said the floodwaters ended up flowing into irrigation ditches that had been used by farmers long before the area was subdivided.

Although 590 homes were damaged, only four were red-tagged and probably will be leveled.

Rick Porter, a plumber whose house was damaged in the flood, said he knows of only one homeowner who had purchased flood insurance.

He's irked because city officials and lending companies must have known of the 1996 flood.

"I would have thought my mortgage company would have told me if I needed" flood insurance, Porter said.

Fernley is a community of working-class people who chose to live there because they couldn't afford more expensive homes in Reno or Carson City.

Many Fernley residents work for modest wages at Amazon.com, printing company Quebecor and other mammoth warehouses along the interstate.

Levine has filled out applications for federal loans and grants. She received one month's free rent on an apartment five minutes away.

But the time will come when she will have to pay rent, along with a mortgage payment for an inhabitable home and costs of repairing that home.

"I don't want to declare bankruptcy. But I don't want to keep paying on a mortgage for a shell of a home for the rest of my life."

The Federal Emergency Management Agency and the U.S. Small Business Administration have set up house in Fernley City Hall.

FEMA offers up to $28,200 in grants for emergency home repairs. The SBA will allow loans up to $200,000 for residents to repair their homes. Its interest rates are as low as 2 percent.

But what is given by the agencies also depends on the applicant's income and other qualifications.

Taking on an additional financial burden is a lot to expect from modest income people like Levine and Porter.

But Bacock points out the federal agencies can assist flood victims in refinancing their existing loans and hopefully bring their total mortgage payments down to close what they are now paying.

No specific cause has yet been determined for the Jan. 5 breach.

At a news conference that morning, Lyon County Undersheriff Jim Sanford said it was likely the ditch bank collapsed because of the deluge of rain the previous day.

About 2 inches fell on Fernley, which normally receives 5 inches of precipitation a year.

McCracken said the Bureau of Reclamation's team of forensic analysts will try to determine a cause for the breach, but he said a specific reason may never be determined.

For Esther Levine and Rick Porter, getting through the next few months will be an ordeal.

Levine walks sadly through what had been a happy home and listens as the building inspector points out more things that will cost money to repair.

She admonishes her son, Joel Dalich, a member of the Louisiana National Guard, to watch where he drops ashes from the cigarette he is smoking in what used to be their dining room.

Then she jokingly tells her son it doesn't matter. She would be better off financially if he accidentally burned the house down.

Levine doesn't have flood insurance, but she is covered for a fire loss.

Contact reporter Ed Vogel at evogel @reviewjournal.com or (775) 687-3901.