From studying to drills to classes, police recruits redefine daily grind

Nathan Herlean was supposed to be on the road by now.

It's 5 a.m. Already 15 minutes late.

He wakes his wife, Brittany. Does she have an extra set of car keys?

Nope.

Herlean's in a panic. He can't be late. No one's ever late.

He searches the house before realizing the keys are locked in his trunk.

He grabs a shovel.

Which window gets it?

Then he stops and goes to Plan B, using the shovel to pry the trunk just enough to insert a hanger. He fishes out the keys and drives away with a few fresh scratches along the trunk.

At least he won't be late. No recruit dares to be late at the Metropolitan Police Department Academy.

By the third week of the academy, Class 6-09 has settled into a routine.

Mornings are reserved for workouts and defensive tactics classes. The rest of the day recruits are in class learning about the law, police procedures and various skills they'll need on the streets.

The course work is college-level material requiring immense concentration and several hours of homework and studying every night. Between studying, shining boots, packing bags and writing out discipline reports (writing a missed definition 25 times, for example), the recruits barely have time to eat and sleep.

Jacob Kelecava, who joined the academy after nine years in the Air Force, drives to the academy an hour before the 7 a.m. start and sits in his truck memorizing flash cards. After 10 hours at the academy, he drives home, packs his bags for the next day, shines his shoes, eats and showers. Then he studies and does homework for several hours.

Then come the discipline reports. Forget a definition, write it 10 times. Trip up on a 400 police code, write the whole set 10 times. Don't give enough effort on an exercise, write a 1,000-word essay on motivation.

No matter the assignment, it's due first thing the next day. That means often staying up past midnight to finish and maybe catch five or six hours of sleep before starting the routine all over again.

The recruits spend Monday through Thursday at the academy, with Friday and Saturday reserved for study groups. Sunday is supposed to be family day, but many recruits study on this day, too.

Herlean said he learned more material at the police academy than at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas getting his business management degree. The academy instructors are more passionate, too.

All of the academy instructors are pulled from the ranks of the police force. They are veteran cops, many having more than 20 years of experience.

All of the instructors work full time at the academy, but that wasn't always the case. Before the academy curriculum and structure were revamped in 2007, three-quarters of the instructors were pulled from their regular police assignments.

Last-minute cancellations and scheduling conflicts cropped up daily, leaving academy staffers scrambling to find substitutes or rearrange class schedules.

Those issues were hard enough to deal with when the Police Department ran four academies a year.

Handling them after the department began monthly academies amidst the hiring of 600 new officers funded by the More Cops sales tax initiative would have been impossible.

With full-time academy assignments, the instructors can focus on teaching.

Officer Kevin Stephens, a 19-year veteran, personifies the passionate instructors at the academy.

During his introductory class on police use of force, he exudes energy as he paces the room during his lecture, interacting with the recruits and pulling them to the front of the class for impromptu demonstrations.

His class covers the major court cases through the decades that have defined what police officers can and cannot do when it comes to using both deadly and non-deadly force.

He pauses to remind them that the job might require them to shoot and kill someone. If they can't make peace with that, they should leave. Nobody does.

Sometimes recruits do struggle with that thought and leave the academy.

It even happened to one of the sons of Lt. Paul Osborne, who runs the academy.

Stephens emphasizes that police officers don't shoot to kill.

"Do we kill anybody? No. We stop them," he says. "We shoot to stop their actions, but that doesn't sell in the media."

The class includes a series of video clips of officer-involved shootings and use of force incidents from around the country. Stephens uses them to educate, pointing out flaws in the officers' techniques and safety awareness. Often they've let their guard down, giving the criminals an opportunity to attack -- sometimes with deadly results.

On a dash camera video, a young officer pulls over a pickup on an isolated road. The driver, a mentally ill Vietnam vet, jumps out of the truck and dances in the road, ignoring the cop's commands.

Then he walks to his truck, retrieves an old military rifle and starts loading it.

The cop shouts at him to stop.

By then it's too late, Stephens later explains.

With his rifle, the driver has the upper hand against the cop and his handgun. The officer screams as the bullets rip into him. Then the screams stop, and the gunman jumps in his truck and drives away.

The officer's hesitation cost him his life, Stephens says.

In deadly confrontations such as that one, the police officer must come out on top, he says. If not, lives are at risk.

"We want to win it. We are in it to win it. We will win it," he says.

After class Jacob Kelecava sits in his pickup, country music on the radio and chewing tobacco under his lip, wondering whether he made the right decision.

The first few weeks at the academy have opened his eyes to the real world of policing, one he's not sure he wants to enter.

"Do I really want to see my partner get shot? Do I really want to go on a scene and see a dead baby?"

A country boy from northeast Ohio, the 27-year-old joined the Air Force out of high school instead of joining the men of his family in the automaking industry.

He became a military police officer and dog handler, serving in Ohio, Germany and Florida. He also spent six months in Iraq, taking his dog on raids and vehicle searches.

"All I saw was fear for my life every day," he says.

After nine years in the Air Force, he got hired by the Metropolitan Police Department and moved from Florida to Las Vegas, his fiancee's hometown, two weeks before the academy started.

Three weeks into the academy he's lost 13 pounds from his skinny frame and gained a ton of doubt.

As a military police officer on base, Kelecava checked out alarms, went to car crashes and gave the occasional courtesy ride -- nothing like the world he's seen at the academy.

Policing is "all I know. It's all I've done," he says. "What am I going to do? Start over at 27?"

Sgt. Dan Zehnder is racking his brain.

Four weeks into the police academy, Class 6-09 has been one of the best he's seen.

The recruits follow the rules and regulations. They know their codes and definitions. They look sharp at inspections.

Classes usually take much longer to shape up.

Maybe it's the class size -- 25 versus the usual 45. Maybe it's the quality of recruits -- they were among the highest scoring on the hiring list. Maybe it's Eugene Yanga's strong presence as class leader.

It doesn't really matter. What's important is ensuring their success doesn't make them complacent, he says.

That comes with challenging the class, pushing the recruits and bringing them together.

Today is one of those challenges.

Zehnder looks to officer Dean Leslie, who oversees the class.

"Are you ready?"

Leslie nods.

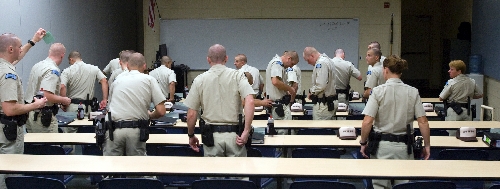

In the classroom, Zehnder orders the recruits to line up in the aisles along the sides of the room.

Run in place. Push-ups. Run in place. Flutter kicks.

The recruits grit their teeth. They groan. They grimace. They gasp.

Then one person dogs it, and it's back to square one.

"When I see people not putting forth the effort, we're going to start over," Zehnder says.

Squats. Arm circles. Mountain climbers. Run.

Then comes the water jug. The recruits stand shoulder to shoulder along the edges of the room. They have 45 seconds to pass the full five-gallon jug around the room.

"Teamwork people," Zehnder reminds them.

They make it. Then 35 seconds. They make it. Then 30 seconds. They make it -- barely.

Twenty minutes in they get a short break.

"You know what's coming," Zehnder says.

Two minutes, 30 seconds. Go.

The entire class runs outside, bolts around the track and sprints to their seats, just beating the time limit. The recruits' chests sag and heave. Their foreheads glisten.

"You barely made it," Zehnder says.

But they made it, and the day is done. After the usual quiz on codes and definitions, the recruits sprint out the academy gate to their cars and head home, thankful another day is done.

They should be thanking the weather.

While the recruits sprinted around the track, Zehnder looked to the sky, felt the 110-degree heat and decided it was too hot to push.

On this day, thanks to Mother Nature, Class 6-09 catches a break.

The next afternoon, the recruits are in the classroom as the day winds down.

Some tidy up the room, while others stretch in silence.

"Fill your bottles up. You know what's going to happen," says Yanga, the class leader.

Remember the plan, he says.

Zehnder and Leslie walk to the front of the class. Zehnder glances at his watch.

"Two minutes, 20 seconds. Go!"

The recruits scramble out the door, this time one row at a time to avoid the bottleneck at the door.

"This is part of coming together and getting through adversity," Zehnder says as the recruits stream outside.

They circle the track, encouraging each other as they sprint back to the classroom. Zehnder counts down.

"Ten"

"Sprint!"

"Five. Four."

"Sprint!"

"Three. Two."

"Get there!"

"One. Zero."

Time's up. The recruits stand at attention behind their seats, gulping water and air.

Zehnder seems satisfied, but he's bothered that they didn't show this kind of teamwork and motivation the day before.

"I'm not sure we're there yet. One little jog around the track doesn't prove anything," Zehnder says as a recruit runs to the bathroom to throw up. "I shouldn't have to be the hammer."

He promises to test them again soon to see just how much of a team they are. Their discipline has been good so far, but if someone slips, they'll all pay, he says.

"If I have to be the hammer, you are not going to like the result," he says.

The recruits can go home, where they'll have their usual homework on top of a 1,000-word discipline report on the importance of motivation and teamwork.

Gathered around their vehicles parked up the street, the recruits celebrate finishing their first round of hands-on tests. Yanga, standing in the bed of his truck, tells them they did great today. They cheer.

"We did good today, but don't go crazy," Dean Vietmeier cautions. "It's only Unit 3."

Of all the 96 days at the police academy, one looms above the rest.

The recruits hear about it from other recruits. They hear it from their friends on the force. They hear it's the worst day of the academy, maybe their lives.

OC day. Oleoresin capsicum, otherwise known as pepper spray.

Every recruit gets sprayed in the face at point-blank range before running through an obstacle course.

If they don't beat the time limit, they get one more chance to retry the test a month later. Fail that and they're out of the academy.

Pepper spray inflames the throat, scorches the eyes and stings the skin. It hurts like nothing the recruits have felt before, and sometimes they freak out.

Officer Sal Mascoli, a defensive tactics instructor, recalls a recruit in a recent class who panicked after being sprayed. He screamed and ran off the field, flailing around before tumbling into some bushes.

The pepper spray tests both the physical and mental limits of the recruits.

On a practical level, the recruits must overcome the pain and finish the course, just like a cop accidentally sprayed in a scrum with a suspect must still get the suspect into custody.

It's also a test of mental strength.

"It's about overcoming fear," Zehnder tells the class before the test. "If you can't handle this, what are you going to do when the guy jumps on top of you? You're just going to curl up in the fetal position."

Michelle Domanico is so worried she's on the verge of quitting just before the test. Only a pep talk from Zehnder changes her mind.

Under normal circumstances, the obstacle course would be fairly simple. Read a license plate. Pump out 10 push-ups. Beat a bag with the baton. Crawl under some poles. Weave through some barriers. Jump a short wall.

But these aren't normal circumstances.

The recruits go in pairs, standing side by side as their eyes and noses are blasted with a stream of the orange spray.

Domanico is one of the first to go and speeds through the course well under the time limit. She throws her hands against the wall along the field and doubles over in pain.

Vietmeier, who already passed pepper spray day when he went through a previous class, holds a hose and dumps water on her head as she wails.

"How'd I do?" she asks.

"You did good," he says.

Zehnder compliments her on the time.

"Aren't you glad you didn't quit?" he tells her.

When it's his turn, Travis Chapman doesn't do well. He makes his way toward the baton bag and freezes.

"It's in my throat!" he yells, his eyelids slammed shut by the pain.

Several officers surround him and scream. They tell him to move, but he stands frozen with his arms outstretched as if he's feeling his way through the dark.

"I need water! I need water, sir!" he says, shuffling toward the sound of the hose.

Mascoli grabs him by the back of his waistband and pulls him back.

"Push it, Chapman!" he yells.

Chapman whacks the bag with his baton and finishes the course, but misses the time. He'll be back.

"He psyched himself out," Zehnder says.

As they finish the course, the recruits head to the wall where they get doused with water and try to regain their senses. They shuffle along the wall, eyelids slammed shut, mouths agape, mucous bubbling from their nostrils, groaning and moaning like zombies.

"It wasn't that bad, was it?" asks a smiling Mascoli, who's already recovered from spraying himself when the test began.

"No, sir," a handful of recruits groan.

The rest remain silent in their misery.

Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@review journal.com or 702-383-0281.

COMING WEDNESDAY: Fighting a war