Medical malpractice reforms still divide

As 59-year-old Richard Krikalo lumbers through the office of a junkyard he helps manage, he bumps into a desk and clips a wastebasket with his right leg.

The Las Vegan is almost blind in his right eye and has trouble adjusting to changes in his depth perception and peripheral vision.

"I go to the buffet and bump into people carrying food," he growls, shaking his head, his static right eye unable to follow his blinking left one, which zeroes in on a visitor. "It's embarrassing. The only time I don't have to worry about bumping into something is when I'm in bed."

He blames a doctor for a botched retina reattachment procedure performed on him in August 2007. But he hasn't found an attorney to take his case. They tell him it's "economically unfeasible" to litigate a complicated case, or that time limitations are an issue.

For that, he blames medical malpractice reforms of the 2004 Legislature.

"With this new malpractice law in place, I can't even get a lawyer to go after who's responsible for what happened," he said, displaying a sheaf of rejection letters from attorneys. "There's hardly any protection for the consumer any more. Now everything is in favor of doctors. It's frustrating.

"I hate frivolous lawsuits. Still, I think that if a doctor really screws up and you lose eyesight, you should be able to find a lawyer to get some decent compensation for what you've lost."

Nearly four years have passed since voters overwhelmingly approved Question 3 on the 2004 ballot -- a measure that physicians called Keep Our Doctors In Nevada. Yet conflicting opinions on how it's working seem as easy to find as a slot machine in a casino.

Doctors, who have realized dramatic savings on malpractice insurance, love it. So do insurance executives, whose companies profit by not having to make large payouts.

Attorneys, who believe a potentially lucrative part of their business is now cut off, hate it. Nevadans such as Krikalo now believe the pendulum has swung too far the other way. Some lawmakers wonder whether the law must be amended to protect the public.

At the heart of the opposing positions is a critical provision of the new law that set a cap of $350,000 on damages for pain and suffering in all cases.

Recovery of economic damages, including loss of future earnings and medical expenses, still remains part of Nevada malpractice law. That, to attorneys, leaves potential plaintiffs by the wayside. Children, homemakers, seniors and people such as Krikalo, who are still able to work despite injury, have no loss of future earnings to calculate. Essentially, these malpractice awards would come out of the $350,000 allocated to pain and suffering, a sum divvied up between the attorney and the client.

In the past, juries would sometimes award seven-figure judgments for pain and suffering to grieving parents who lost a child to medical negligence or to an individual whose quality of life had changed because of a physician's mistake.

That all changed on Nov. 24, 2004, the date the reforms went into effect.

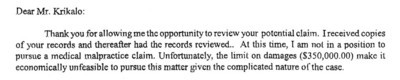

Now Nevadans who believe they have claims often receive letters from attorneys similar to one Krikalo received from attorney Janet Markley in July of this year: "Unfortunately, the limit on damages ($350,000) makes it economically unfeasible to pursue this matter given the complicated nature of the case."

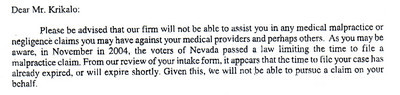

Time was getting short for Krikalo's desire to pursue a claim when he contacted local attorney Gerald Gillock. The Legislature had enacted a one-year time restraint on filing malpractice claims compared with the previous two-year deadline.

Gillock, in rejecting his case, told him as much.

"It appears that the time to file your case has already expired, or will expire shortly," Gillock wrote to Krikalo. The letter was dated Aug. 12.

Doctors, who fought a bitter campaign against trial lawyers in 2004, have little sympathy for attorneys who try to bolster a malpractice case. They long have believed trial lawyers abuse the system and file frivolous claims hoping for settlements or unreasonably large jury awards.

The physicians would rather talk about how they have seen their malpractice insurance costs drop an average of about 20 percent to 30 percent since the 2004 reforms.

"The morale of physicians is much improved," said Dr. Jerry Jones, president of the Clark County Medical Association. "They're much happier doing medicine now and our doctors are staying in Nevada."

Dr. Weldon "Don" Havins, who held Jones' post until he took over as president of the Nevada State Board of Osteopathic Medicine earlier this year, said that until reforms were implemented the state didn't attract many new physicians to serve the burgeoning population.

He points out that the net gain in licenses issued to doctors who chose to practice in Clark County shrunk to a low of seven in 2002.

Just the promise of medical tort reform passage in 2004, he noted, brought a net gain in licensees that year of 212.

"Since the implementation of the 2004 medical tort reforms, the net gains in Clark County physicians has continued and stabilized," Havins said.

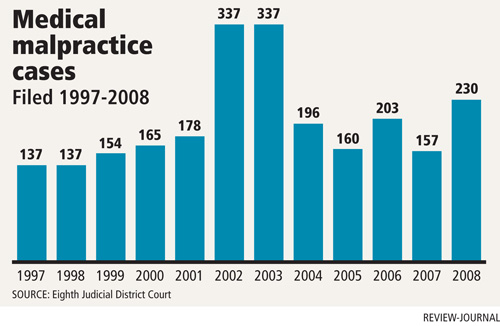

Havins for years has regularly tracked the number of malpractice lawsuits filed in Clark County. He said a substantial decrease in medical malpractice filings -- 337 cases were filed each year in 2002 and 2003 -- has been especially heartening to physicians. In the years 2004 to 2007, the number of cases filed ranged from a low of 157 last year to a high of 203 in 2006.

There have been 230 cases already filed this year. But he said that is probably an anomaly, reflecting cases brought in the wake of the current hepatitis C crisis in Southern Nevada.

Only two cases that were filed in Clark County District Court after the 2004 reforms have gone to a jury. One ended with a $100,000 award and the other, $495,000.

To Havins, the fact that the number of cases filed since 2004 is higher than those filed in the five years prior to the "crisis years" of 2002 and 2003 proves that Southern Nevadans still have a solid legal remedy for medical negligence.

"Plaintiffs apparently are not having trouble finding attorneys to take their cases," he said.

That's not how attorneys analyze the statistics.

Jim Crockett, an attorney who quit practicing in the medical malpractice arena, said the lawsuits now filed are basically on behalf of individuals where future earnings at are stake, including families who lose a breadwinner because of medical negligence.

"My cases were overwhelmingly centered on the wrongful death of children, housewives or senior citizens, who had no economic damages," he said. "But for what I had to do to win them, the outcome now isn't satisfactory for either the client or me. If a client gets a little more than $50,000 after four years of stressful litigation, they don't feel it's worth it."

Gillock, another veteran plaintiff's attorney, said the reason for the steady rise in the number of lawsuits, despite a dramatic drop-off in pain and suffering cases, is simple: "There is a lot of medical malpractice out there."

Even if Gillock is correct, the new cap that deters possible huge jury awards for pain and suffering has resulted in new malpractice insurance carriers entering the Nevada market.

The increased competition, Havins said, has helped bring insurance premiums down for doctors, who, according to studies done by Medicare and Medical Economics, spend between 3.2 percent and 3.9 percent of their practice incomes on malpractice insurance.

According to Janice Moskowitz of the Nevada Division of Insurance, there were six major insurers who were providing insurance for physicians and surgeons in 2004. Today there are eight authorized carriers.

Sheldon Davidow, chief executive officer of Medicus Insurance Co., said his Texas-based firm decided to enter the Nevada market because of Question 3's passage.

He said that today he can offer excellent practitioners significant savings on insurance premiums. For instance, a family practitioner can receive a premium between $14,000 and $18,500 per year, compared to $25,000 before the reforms.

Policies for specialists in obstetrics and gynecology, he said, now range between $78,000 and $105,000, well below the $150,000 to $200,000 paid five or six years ago.

Davidow said surgeons who had been paying $100,000 for coverage can now get premiums between $55,000 and $70,000 a year.

According to Salary.Com, the median salaries for general surgeons in the West is $292,000, $235,000 for OB/GYNs, and $158,000 for family practitioners. Robert Byrd, president of the Independent Nevada Doctor Insurance Exchange, said the entire medical profession in Nevada no longer has to worry about carriers leaving the state, as they did earlier this decade.

"Because of the reforms, Nevada is no longer seen as one of the problem states," said Byrd, whose firm now offers policies at rates similar to those quoted by Davidow. "It's now seen as a very attractive place to do business."

The chair of the state's Legislative Committee on Health Care, Assemblywoman Sheila Leslie, D-Reno, is anything but upbeat after the reforms.

She says she'll be surprised if legislators don't revisit the 2004 legislation that had Dr. Dipak Desai, the Las Vegas physician now at the center of the Las Vegas Valley's hepatitis C crisis, as its biggest single financial backer with a donation of $20,000.

"We have to be fair," Leslie said. "What has happened with the whole hepatitis C tragedy is the best argument why the caps should be revisited. This scandal has really heightened interest in what caps for pain and suffering mean. Doctors are overprotected and the law really does not protect the patients."

Before the law went into effect, it was the doctors who felt unprotected. They said that, without tort reform, physicians would leave the state.

But, how many doctors left Nevada before the law went into effect is anybody's guess. The nation's General Accounting Office couldn't reach a figure and deemed the ever-changing statistics cited by Nevada physicians to be exaggerated, anecdotal and inaccurate.

Leslie believes the ability of an individual to pursue a liability lawsuit for improper treatment provides an additional incentive for a doctor to follow good medical practice.

Seldom, if ever, Gillock said, will an insurance carrier today settle for the maximum $350,000 for pain and suffering.

"There's no incentive to," he said. "They know you would have to pay the experts again at trial. Sometimes $500 an hour." Under the 2004 reforms, attorneys' contingency fees also were cut.

Gillock said he had recently took a malpractice case where a stay-at-home mother died. He spent $65,000 on experts and the case settled for $300,000.

Once he was reimbursed for the costs of the experts, the husband and four children received $135,000 from the settlement. And Gillock made around $70,000 for a case that was litigated for more than two years.

"I'll be honest with you," he said. "Nobody thought the stress of that litigation was worth it. And most attorneys couldn't afford to do that."

But Gillock said he continues to take cases knowing there will be little payout, hoping one day a jury verdict can be appealed to the Nevada Supreme Court. Doctors, he said, have become a special class, one inured from the kinds of compensation that other entities might have to pay if found liable for serious injury or death. A moving company, he said, could be on the hook for millions if an employee negligently ran over a child. A doctor's exposure is a fraction of that if a child dies of medical malpractice.

"I know if we get the right case it will be ruled unconstitutional," he said.

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim @reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.