Ex-POW from Las Vegas remembers comrades lost in the Korean War

Gene Ramos remembers December 1950 as the coldest winter in 100 years.

He remembers chipping away with a trenching tool to make a divot for a foxhole in the frozen Korean soil.

Today, as veterans and families across the nation pause for Memorial Day, Ramos said he will be thinking about the comrades he lost on those battlefields and another friend who endured prisoner-of-war hardships with him.

Sixty-four years ago on the Korean peninsula, after pounding the terrain for hours, Ramos managed to carve only an 8-inch-deep depression where he could sleep without freezing to death before his heavy weapons company for the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division set up a line of defense.

This line, one of three, was established so that embattled Marines and soldiers could make an exodus to the safety of ships on the coast from tens of thousands of invading Chinese combatants at Chosin Reservoir.

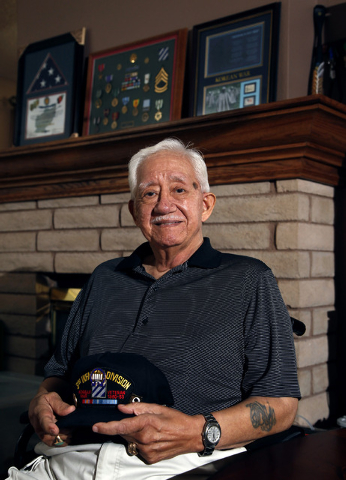

“That’s where we really got stomped,” Ramos, 81, recalled, sitting in a wheelchair Thursday at the dining room table in his east Las Vegas home.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur earlier had launched a hasty invasion with a goal to bring U.S. troops home by Christmas.

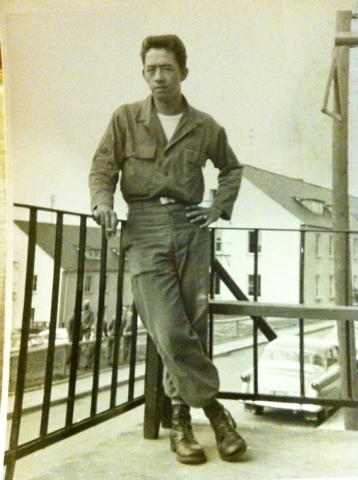

Without winter gear, Ramos, an Army private first class, easily could have died that night from bone-chilling exposure. The shallow foxhole “was the only thing that kept me warm,” said Ramos, now commander of the Las Vegas Chapter 7-11 of American Ex-Prisoners of War.

BRUSH WITH DEATH NO. 2

But that wasn’t his closest brush with death during the Korean War. That came later under milder but more dangerous conditions near the 38th parallel. That’s where his unit — Company H, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division — had dug in along what they called the “Kansas line,” the toughest place for the enemy to penetrate.

“I had dug my machine gun on this little part of the ridge with a nice escape route. In case I got hit real hard, I could get my assistant gunner and my ammo bearer out of that hole, and we could be moving back.”

Then a captain came along and told him to relocate the .30-caliber machine gun and 10 boxes of ammunition down in the ravine. “But I said, ‘If we get hit there’s no way we can come out. We’re dead ducks down there.’ ”

That didn’t sway the captain, who wanted machine gun coverage closer to a barbed-wire boundary. So, Ramos and his team hustled to dig a hole downhill not far from the wire, with the gun’s barrel poking from a slot formed by a pair of sandbags.

“We got hit that night,” he said. It was about 9 p.m. on April 24, 1951.

“I heard this cutting of barbed wire. ... Somebody’s trying to come through. All the guns are pre-loaded. So you pull back on the handle and push it forward. It’s fully loaded now. Ready to go,” he said. “I’m looking down, and I see a big mass in front of the barbed wire.”

Ramos opened fire, unleashing 2,500 rounds through the darkness. His gun was equipped with a device to hide flashes so it would be difficult for the enemy to target his location as rounds flew out the air-cooled barrel.

“I emptied one box. I said, ‘OK, another box.’ And that went on for quite a while because once I opened up, everybody else opened up.”

Eventually, all 10 boxes of ammo were gone. Ramos knew that in three minutes, after he purposely destroyed his machine gun with an incendiary grenade, enemy soldiers would be able to zero in on his location. So he started throwing hand grenades as they approached.

“We must have thrown eight or ten, and I had one in my hand when four Chinese came up onto our hole. Of course I had the pin out of it already. And I’m standing there with it in my hand. They could see I had something in my hand but they didn’t know what it was,” he said.

He told his assistant gunner, Perry Osborne, to stay down in a corner “and don’t get up because I’m going to hand (them) this grenade. And when I do it will only take three seconds for it to go off.”

So he handed them the grenade, counted to three and jumped in a “tiny hole” he had dug for an escape route. After the grenade exploded, he ran toward the barbed wire and hid. He had a .45-caliber pistol but no bullets. He had been shot in the arm and was bleeding, but not badly.

A HERO’S STORY

Chinese troops overran this area near Taejon-ni and captured wounded U.S. soldiers, including Ramos.

Among those captured was his friend, a machine gun squad leader from Company H’s second squad, a Japanese-American corporal from Gallup, N.M., named Hiroshi “Hershey” Miyamura. He had managed to survive hand-to-hand combat with a bayonet, killing 10 Chinese soldiers before manning another machine gun to provide cover for his men while he told them to flee.

“He killed more than 50 enemy before his ammunition was depleted, and he was severely wounded,” Miyamura’s Medal of Honor citation reads. “He maintained his magnificent stand despite his painful wounds, continuing to repel the attack until his position was overrun. When last seen he was fighting ferociously against an overwhelming number of enemy soldiers.”

Both Ramos and Miyamura were marched northward by their captors and endured the rest of the war in North Korean prisoner-of-war camps.

“Hershey was very sick most of the time,” Ramos said.

After about a year in Prison Camp 1, Ramos was allowed to write a letter to his parents, who had received only a telegram saying that he was missing or killed in action. When the letter arrived, his mother knew he had written it because of the way he spelled some words and the way he signed it, “Your loving son.”

For the most part, they survived on what Ramos called “liquid rice — a lot of water and very little rice. You had your little bowl and you got in line and they’d scoop one scoop and put it in there. Of course you went off to the side and slurped it down,” he said.

“I weighed about 170 pounds when I got captured. When I came back across the line I was 98 pounds.”

Ramos and Miyamura rode back in an ambulance together. “We were throwing our clothes out the window of the back door because we said, ‘Hey we didn’t want any more of these Chinese clothes.’ ”

When the ambulance stopped and the back door opened, “there was all this brass. All these generals, colonels. Everybody was standing there. I said, ‘What the hell did I do? I didn’t do anything.’ So I moved on past them. They weren’t waiting for me. They were waiting for Hershey. That’s why,” he said, flipping a Medal of Honor coin on the table.

Miyamura’s Medal of Honor was kept secret until they were repatriated when they walked down the steps at Freedom Bridge on Aug. 28, 1953. The nation’s highest military award was presented to Miyamura by President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the White House two months later.

Ramos stayed in the Army and served in the Vietnam War. He was honorably discharged as a sergeant first class in 1972.

“Freedom,” he said, “you don’t know what you have until you lose it. All of these people in the United States think freedom is free. It’s not free. If it weren’t for all these different wars we had, we wouldn’t have freedom here. If MacArthur and Eisenhower hadn’t did what they did ... we may be learnin’ German right now. Or Japanese.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.