Mining plan dredges up resistance

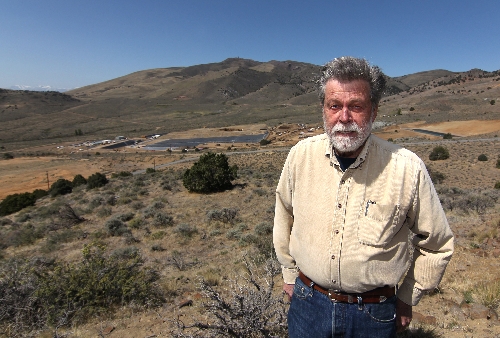

Standing at the edge of a 500-foot pit left by a failed mining operation, David Toll worries that history will repeat itself if Comstock Mining Inc. digs more holes into these mountains he has loved for the past half-century.

"Aliens have invaded and they are ravaging the landscape," Toll said of the abandoned open pit mine at the southern edge of Virginia City and a new one being dug next to the main road through this historic area of Northern Nevada.

"This is a corporate version of home invasion," he said. "This is hard, cold, callous heavy industry, operated for the benefit of investors far away, an extreme intrusion into our quiet lives in these peaceful towns."

But Nevada became a state 148 years ago this fall largely because thousands of adventurers, many bankrolled by investors, poured into these craggy mountains to dig billions of dollars worth of gold and silver out of what became known worldwide as the Comstock Lode.

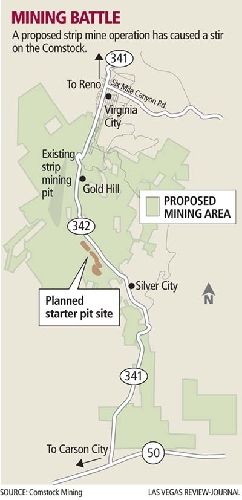

Over the next 10 to 15 years, Comstock Mining wants to expand its operations to nearby areas and extract minerals worth $3 billion. Workers operating heavy equipment are now cutting sides off mountains and finishing the processing facilities. The first gold and silver could be poured in late summer.

"We are just scratching the surface with the 3 million ounces," said Corrado De Gasperis, president of CMI.

MINE DUG NEXT TO HIGHWAY

As Doug McQuide drives his truck on a rocky road past where his company is completing its crusher plant and heap leach pad, he acknowledges their Lucerne Mine lies just a few feet off state Route 342, the primary highway linking Virginia City, Gold Hill and Silver City.

Bulldozers already have dug about 50 feet into the ground and he estimates they will dig another 150 feet down in the open pit mine.

If the company expands its mining operations as expected in a few years, it will be necessary to move the highway. The same highway was moved a couple of generations ago to accommodate a mining operation, said McQuide, the company spokesman.

CMI has spent $30 million on its operations in the past year. It has hired 60 workers, almost all from the immediate area.

It has posted a $5 million reclamation bond and pledged to give a 1 percent royalty to local county governments for restoration purposes. It also pledges to give a 1 percent royalty to a private foundation that will create a mining history and cultural center to attract more tourists to the Comstock, he said.

Comstock already has repaired parts of the framework of the Dayton Consolidated Mine that was abandoned before World War II and intends to repair four other abandoned mines as a way to create living mining history programs for schoolchildren and visitors, according to McQuide.

Surface mining is cheaper than underground mining and that is a key reason why the Lucerne Mine is open pit. But in the future, as the company expands into other portions of the 6,400 acres of land it owns or controls, some mining will be underground, he said.

During the Comstock boom in the 19th century, virtually all mining was underground. More than 700 miles of tunnels were excavated in mines that went as much as 3,000 feet underground.

Even now, Virginia City occasionally experiences sinkholes caused by underground cave-ins. One occurred just outside a school.

Barring a collapse in prices, McQuide expects the Comstock will produce rare minerals here for decades. Gold now sells for $1,567 an ounce, but he said the company can be successful as long as it stays above $800.

Production should hit 12,000 ounces this year, and then expand to 20,000 to 30,000 ounces a year, he said. With expansion to new mines southeast of Silver City, the company hopes annual production will reach 100,000 ounces.

RESIDENTS TAKE SIDES

Rather than rejoicing about the return of mining to their economically depressed region, residents like Toll, an author known best for his Nevada travel guides, have campaigned to keep mining out, at least open pit mining.

In front of some homes in Virginia City, population 858, and in the much smaller hamlets of Gold Hill and Silver City, residents have posted "no strip mining" signs. A few have put up larger "Mining Works for Nevada" posters, but opponents say those are homes of mining company workers.

Conflict reigns in what had been sleepy towns known for their aging hippies. Many moved here from San Francisco in the 1960s when Virginia City had a thriving music scene, once even hosting Janis Joplin.

"This is a quiet rural community," said resident Bob Elston, a retired archaeologist, about his home in Silver City, a community of maybe 300 people. "We don't want a big mine in it and all the drilling and blasting. All the sounds from trucks drive you nuts."

"This is a gorgeous area," said Sheree Rosevear, owner of DooDads Cybercafe and Emporium in Silver City. "I'm not against mining. I am against open pits."

Elston fears land values will drop even more along the depressed Comstock and residents eventually will have to sell at losses.

Unemployment in Storey County, home of Virginia City and Gold Hill, stands at 12.8 percent. Silver City, in adjacent Lyon County, has an unemployment rate of 15.6 percent.

Former Storey County Sheriff Bob Del Carlo said the Comstock mining operation has helped the economy. Mining is why the three communities exist.

"Those who are opposed to it have never been around mining," Del Carlo said. "Mining is part of Nevada."

"Mining made us," said Billy Megan, a Virginia City resident. "I have heard they are hiring locals."

But Bill Pearson has lived here for 34 years and remembers the Houston Oil and Minerals debacle.

The abrupt 500-foot dropoff was carved in Gold Hill at the southern edge of Virginia City by the Texas-based company in 1979-83, a time when gold peaked at $800 an ounce.

Gold prices eventually fell and Houston fled, leaving its cavity right out the back doors of several homes. Old-timers talk of a four-wheeler plunging down the hole, but there is no known record of anyone dying. The crevice remains a dangerous attraction for children and off-roaders.

"People move here for the scenery," Pearson said. "They don't want it destroyed."

Those new to the Comstock might not notice any difference. Abandoned mines and old piles of ore are scattered in every direction, the legacy of 150 years of mining. The scars from mining are part of the scenery.

Tourist traps in Virginia City feature mine tours and mining museums.

Pay a couple of dollars and you, too, can pan gold at one attraction.

THE LATEST SKIRMISH

Despite a U.S. Bureau of Land Management order blocking it from using disputed right of way, Comstock Mining had anticipated pouring the first ounces of gold and silver from its Lucerne Mine, about four miles south of Virginia City, by this summer.

Leon Thomas, field manager of the BLM's Sierra Front Field Office, issued a cease-and-desist order May 21 preventing the company from hauling ore from the mine to its processing facilities on the disputed right of way.

"They were blocking access to public lands through gates and a checkpoint that they didn't have a clear right to," Thomas said. "They won't be able to operate until they come in with a proper application."

Thomas said an extensive environmental review could be required, a step that might "take a while" to complete.

The mining company quickly announced it would appeal the BLM decision and said its efforts to produce precious metals would "proceed on schedule."

Later CMI officials gave a detailed response to the BLM that they have been using right of way that private landowners and other mining companies have used since 1869.

One doesn't give up easily after spending $30 million without an ounce of gold to show for the effort.

But neither have the mine opponents. They quickly fired off emails stating that CMI has been violating the cease-and-desist order.

They haven't declared victory, though. They predict the mining company will forge ahead.

"They have no apparent regard for the regulations or the requirements of their permits at state and local levels," said Robbin Cobbey, a leading critic of open pit mining. "Instead they just plow forward hoping no one will notice or do anything."

De Gasperis said he can understand the fear of residents in light of the Houston Oil and Minerals disaster, but CMI does things differently.

"Don't judge us on what happened before," he said. "Houston left a bad legacy. We are not a fly-by-night operation. We believe the groups that oppose us are relatively small. They aren't bad people. They just believe surface mining cannot be done in a responsible way."

PROFITABLE FUTURE SEEN

The cease-and-desist order hasn't deterred investors from buying shares of "LODE" on the New York Stock Exchange. Sale prices before the cease-and-desist order May 21 were $1.78 a share, a precipitous drop from $4 a share a year ago, and the price fell to $1.63 on Wednesday. But by Friday afternoon LODE had rebounded to $1.82.

De Gasperis remains optimistic. He said tests show there are at least 3 million ounces of "indicated" gold and silver in just a tiny fraction of the land his company controls.

While it is not yet "proven" reserves, De Gasperis said that will be shown once they begin extracting gold and silver.

"The investors are waiting until the company is in production," he added.

The dream for Toll is that gold prices will plunge significantly and drive Comstock Mining out of the Comstock, just as it did for Houston. He realizes economics is the only surefire way to rid the country of open pit mining.

"Naturally I am pleased that the feds have put a halt to the arrogant behavior of this rogue company. And I am astonished, too. It's like Amarillo Slim going in on a queen high, a bluff so brazen it defies common sense."

"My instinct tells me CMI may well have - must have - something else up its corporate sleeve - but what?" Toll asked aloud.

Contact Capital Bureau Chief Ed Vogel at evogel@reviewjournal.com or 775-687-3901.