A Sisolak run for Nevada governor would begin with campaign coffers full of cash

Clark County Commission chairman Steve Sisolak is staying tight-lipped on whether he’ll run for governor of Nevada in 2018.

However, one thing is certain: If Sisolak runs, he’ll have an unprecedented head start on campaign fundraising.

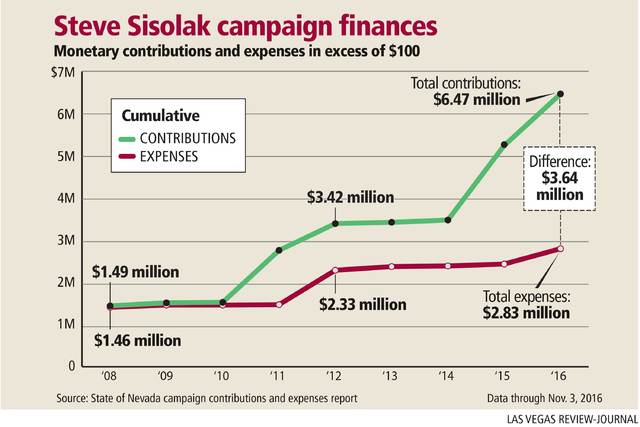

With two years until Nevada’s next gubernatorial election, Sisolak expects to have $2.8 million to $3.2 million in cash after he finishes paying campaign expenses related to his recent re-election to a third four-year term on the county commission.

State law allows Sisolak to roll those funds over to his next campaign if he so chooses.

“That’s an incredible war chest,” said Rory Reid, Nevada’s Democratic gubernatorial candidate in 2010 and son of Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev. “When I was running I was trying to get $1 million by the beginning of (2009) to appear formidable. Without question, Steve is formidable.”

When Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval successfully ran for re-election in 2014, campaign finance records show his coffers held about $950,000 two years out.

In comparison, Sisolak raised close to $1.8 million in 2015 and $1.2 million in 2016. As of early November, he had only spent about 14 percent of that money, campaign finance reports show.

And after his second election campaign for the commission seat ended in 2012, Sisolak apparently had about $1 million left in his war chest, according to finance reports.

“He has excelled at fundraising. He’s very skilled at it, and he doesn’t mind doing it,” said longtime Democratic political strategist Dan Hart.

But even with all that cash-on-hand, Sisolak will only confirm that he’s considering running. Nevadans haven’t elected a Democrat as governor since Bob Miller in 1994.

“Before we make a decision we’ll do some polling statewide to determine what the issues are, what my chances would be of success,” Sisolak said last week. “I won’t do anything without talking to my family first, and my advisers and my supporters.”

If Sisolak decides not to run for another office, state law allows him to return his excess funds to his contributors, donate the money, or contribute it to other candidates.

‘AN EFFECTIVE POLITICIAN’

Sisolak, 62, has been a familiar face in Nevada politics for nearly two decades.

Born in Wisconsin in 1953, Sisolak received a bachelor’s degree in business from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 1974. He moved to the town of Spring Valley in Clark County during his early 20s and graduated from UNLV with a master’s degree in business administration in 1978.

From 1998 through 2008 he was a member of the state Board of Regents, the elected body that governs Nevada’s higher education institutions. In 2008 he resigned from that board after being elected to the commission’s District A seat.

Today he holds the same seat on the governing body of Nevada’s most populous county, where he’s known for being a fiscal conservative and for his outspoken demeanor. His fellow commissioners have elected him the board’s chair twice since 2013.

Sisolak made headlines in 2014 when he toyed with the idea of running in that year’s gubernatorial election. But after spending about $70,000 on polling and research he decided against it, saying the timing was not right.

The 2018 election could hold better opportunities for Sisolak, Hart said.

Sandoval will be terming out of office, and Hart said Sisolak is better positioned to run “than virtually anybody on the Democratic side.”

“He’s got a great reputation as an effective politician but also as an effective leader and an inside player,” Hart said. “He knows how to lead. He knows how to deal with political players. He knows how to navigate the corridors of power virtually better than anyone I’ve seen on our side of the aisle.”

FIRST STATEWIDE RACE

Sisolak’s burgeoning war chest and penchant for the public spotlight means he would be a far different candidate from the Democrat’s 2014 nominee for Nevada governor.

That year, Bob Goodman raised less than $10,000 during his failed run against Sandoval, who won with 70 percent of the vote. While Goodman was the state’s economic development director in the ’70s, he was relatively unknown in 2014.

“It’s hard to draw a comparison because Goodman was a default candidate. No Democrat really had the stomach to take on Sandoval,” said Michael Green, a historian and professor at UNLV. “Sisolak comes into a completely different situation.”

Of course, Sisolak will probably need to raise millions more to run a competitive campaign for governor.

When Sandoval first successfully ran for the office in 2010, he collected nearly all of his $5 million in the 14 months before the election. Between his first election to governor and second in 2014, the former federal judge raised close to $5.1 million, campaign finance reports show.

Sisolak faces another considerable hurdle.

“I’ve never run in a statewide race before so it’s a little different for me. My campaign was set up for county,” he said. “It’s something we have to talk about and talk through how well I would do in those (rural) areas.”

Eric Herzik, chair of the political science department at the University of Nevada, Reno, said that while Sisolak is one of Southern Nevada’s best known politicians, he will have to prove himself to residents of the state’s northern counties if he wants their votes.

“There is a lingering north-south suspicion gap,” Herzik said.

“The wariness the north has is: ‘OK, are you a complete advocate for the south at the expense of the north?’” he continued. “The northerners see the south as taking a disproportionate share of resources.”

REPUBLICAN ROADBLOCKS

For better or worse, Sisolak also will be known as an outspoken champion for the deal to build a $1.9 billion stadium in Las Vegas using $750 million in public financing. He served on the Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee, which sent Sandoval recommendations to increase the county’s hotel room tax to fund the stadium project and expansion of the Las Vegas Convention Center.

The stadium funding plan has been a divisive issue for a large number of county residents.

Nevada’s largest union, Culinary Local 226, implied in a video earlier this year it planned to oust politicians who favored the stadium deal. Subsequently a coalition of six unions, including Laborers Local 872, formed to support the project.

“It cuts both ways,” Herzik said of Sisolak’s support of the stadium. “When organized labor shows up in a Nevada election they are crucial. But they’ve also sat out elections and that really hurts Democrats, and we saw that in 2014.”

And while he wouldn’t run against an incumbent, Sisolak could find himself pitted against Sen. Dean Heller, R-Nev., Lt. Governor Mark Hutchison or Nevada Attorney General Adam Paul Laxalt, another prominent Republican.

“If it was a Heller-Sisolak race, I say Heller starts as the favorite. He has everything that Sisolak has and more of it,” Herzik said. “Dean Heller would not have to reintroduce himself to any part of the state.”

Regardless, Herzik and Hart agreed, Sisolak’s prep work has made him the Democratic Party’s frontrunner if it wants to take back the governor’s office in 2018.

“He has all the building blocks, he has all the ingredients, now the question is whether he really wants to do it,” Hart said.

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.