Rattlesnakes attract attention at Great Basin National Park

When the weather warms and the snow begins to melt in a month or two, rattlesnakes will emerge from their communal dens at Great Basin National Park and slither forth to forage and mate.

And park staff members will know just where to look for them.

Over the past two years, researchers have surgically implanted tracking devices inside nine Great Basin rattlesnakes to monitor their movements and their tendencies.

"For such a widespread species, it's surprising how little is known about them," said Bryan Hamilton, the park biologist heading up the study. "It's really amazing what you can learn about an animal when you put a radio device in them."

The research already has led to a change in the way the park deals with close encounters of the rattling kind.

When so-called "nuisance snakes" were caught at campgrounds or, say, in the park superintendent's backyard, the old practice was to release them a mile or two away. But such long-distance relocations were stressful -- and sometimes fatal -- to the snakes, which would labor to return to their original territory, often exposing themselves to the elements in the process.

Under the park's new protocol, problem snakes are moved a more survivable distance of between 100 and 200 meters, because the telemetry study showed they tend to avoid people and their capture sites after they have been caught.

"It's affected the way we manage wildlife," Hamilton said of his work.

"It has a lot to do with visitor safety and rattlesnake protection," said Tod Williams, Great Basin National Park's acting superintendent. "With these short-distance moves, none of the snakes have died."

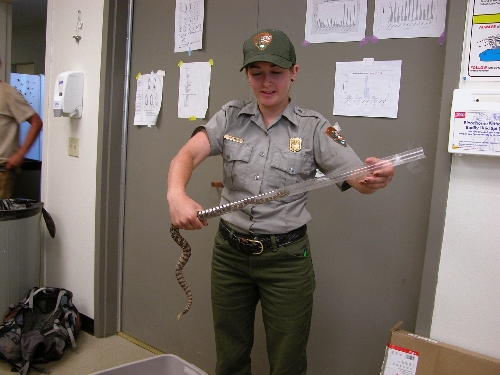

HOW IT'S DONE

So how do you plant a tracking device in a rattlesnake? Very carefully. And repeatedly, since the batteries in the devices wear out after about two years.

First the rattler is caught -- literally picked up off the ground -- using a pair of "snake tongs," Hamilton said.

Then the snake is anesthetized, and a 3-inch, egg-shaped transmitter is surgically implanted about two-thirds of the way down from its head, in a part of the body with no vital organs.

The snakes are usually released within 24 hours of surgery and are "back to their old selves" after two or three days, Hamilton said.

The snakes heal completely within a month or so, he said. "If you didn't know where to look, you wouldn't be able to see the scar from the incision."

Hamilton and company check in on their snakes every two weeks or so. To find them again, they walk around with a handheld device attached to what looks like a scaled-down version of a rooftop television antenna.

If the terrain is right, a transmitter can be picked up from as far as a mile away and lead researchers to within about 5 feet of the snake.

"We can sometimes tell which rock they're under even when they're not visible. It's an incredible tool," Hamilton said.

HOW THE RATTLERS LIVE

The research is focused on three main watersheds in the 77,000-acre park about 300 miles northeast of Las Vegas.

The tracking devices have helped park officials identify five more den sites in that area, bringing the total number of known hibernacula to 15.

The snakes seem to prefer to spend their winters on steep, south-facing slopes, where they nestle together in slots that extend several feet into the ground, deep enough to get the cold-blooded critters below the frost line.

Hamilton said they "hibernate communally" in groups that range from 10 to 50 snakes, most of them related.

"One big happy family," he said.

The snakes usually return to the same den year after year, generation after generation.

Newborn rattlers are thought to find their way to their mother's den by following her scent.

"If you find a good place to spend the winter in the Great Basin, you stick with it," Hamilton said.

Snakes in the park typically emerge from hibernation sometime between mid-April and mid-May. A few warm days in a row is all it takes.

They mate in July, and the young are born in September, usually six to eight at a time.

By the end of October, the snakes are back underground for the winter.

Hamilton said the tracking devices also have given the research team a glimpse of rattlesnake behavior few people ever witness, including an encounter between two males who were caught on video as they reared up in the air and wrestled for the affections of a nearby female.

"Without the transmitters, we never would have seen that," he said.

The seven males and two females currently being tracked have grown accustomed to their regular visits from National Park Service employees.

"They don't even rattle anymore," Hamilton said.

SNAKE, VISITOR PROTECTION

The overall goal of the study is to better protect rattlesnakes and park visitors by learning as much as possible about where the snakes live and how they behave.

Hamilton said rattlesnakes are often misunderstood and irrationally feared.

None are known to be aggressive toward humans, he said, and the Great Basin variety is among the least "feisty" and least toxic he has worked with.

Hamilton said not a single person has been bitten by a rattler at Great Basin National Park in his 11 years there.

Throughout the region, bites occur maybe once every year or two, he said, usually when someone is trying to catch or kill a rattlesnake.

"You have to really do something to deserve to get bit almost every time," he said. "Unfortunately, a lot of people still think it's their job to kill rattlesnakes."

It's against the law to kill a rattlesnake inside the national park. It's also "unnecessary," said Hamilton, who has been handling venomous snakes since he was 15 years old.

In the coming months, he and his team plan to implant more rattlesnakes and expand their research by collecting small samples from the rattles of the snakes they catch.

Hamilton said the pieces harvested from the snakes will be too small to damage the rattle or otherwise hurt the snake.

Researchers hope the samples can be used to determine what the snakes are eating, how often the females reproduce and even track drought events.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.