SEPT. 11 TERROR ATTACKS CONTINUE TO TAKE A TOLL

Seven years ago today, nearly 3,000 people were killed in terrorist attacks that destroyed the World Trade Center in New York City and damaged the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Also among the dead were the passengers and crew of United Airlines Flight 93, who fought the terrorists, causing the plane to crash in a field in Pennsylvania. But the story does not end there. For those who responded to the World Trade Center to help victims and later searched desperately and often futilely for survivors, the trauma of that day has had to be absorbed into everyday life. Here are the stories of two valley men with intimate connections to that fateful day.

The 9/11 tour isn't finished, yet Tony Quaranti can't continue. The 55-year-old just described a twisted chunk of I-beam from the north tower. He keeps it in the garage of his Las Vegas condo, along with a sliver of World Trade Center molding and what he believes to be part of one of the two hijacked planes.

Quaranti presses his free hand to his face in a fist. A violent cough explodes.

"Excuse me!" the former New York City sanitation supervisor says, turning to walk back inside the condo. The garage isn't the only place Quaranti keeps remnants from that terrible day seven years ago. They're also in his lungs.

For nine months beginning Sept. 12, 2001, Quaranti says he inhaled a cocktail of aerosolized poisons -- along with pulverized human remains -- 12 hours a day, seven days a week. His respiratory problems now include fibrosis (scarring), atelectasis (collapsed lung tissue) and reactive airway dysfunction syndrome.

The last one is commonly referred to as "9/11 cough."

"The airways are now overly reactive to nonspecific irritants," explains Dr. Stephen Siegel, the Manhattan-based pulmonary specialist Quaranti has seen since 2004. "If a person with (RADS) just breathes in a little pollen, their lungs think they're in a forest fire."

Siegel says he has seen "a couple (of) hundred" similar cases in ground zero workers. Though usually nonfatal, the condition is incurable. It can get worse, but not better.

"I just live my life," says Quaranti, who moved to northwest Las Vegas with his wife in 2005 because the New York winters worsened his breathing.

"I try not to worry about it."

Quaranti directed the flow of garbage trucks in and out of the 16-acre rubble pile. For the first few weeks, however, his job was the same as every other responder's.

"We searched for survivors," he says.

All Quaranti found was death.

"We'd have to put them in red bags -- arms, limbs," he says. "You would find just a finger."

According to the World Trade Center Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program at Manhattan's Mount Sinai Medical Center, the rate of exposure-related illness is 70 percent among the 40,000 ground zero workers it monitors. This includes 12,000 New York Fire Department firefighters and 3,000 emergency medical technicians as well as 25,000 police officers, other firefighters, volunteers, transit workers, communications workers, construction workers, building cleaners and sanitation workers.

"The highest frequency of disease is in the people who were most heavily exposed," says Dr. Philip Landrigan, director of the program.

Quaranti says that some of the 1,500 sanitation workers on site are already dead of what he believes to be exposure-related illnesses.

"A couple of guys died from cancer, a couple had liver problems," he says.

Causality is a hotly contested issue, however. When asked how many first responders have died as a result of their exposure, Landrigan replies: "I couldn't begin to tell you."

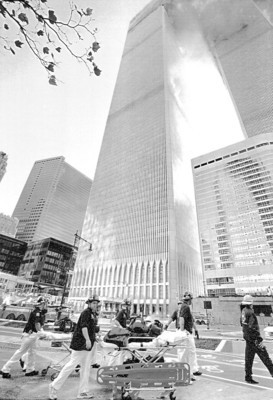

Michael Roberts scans a photo hanging in the office of the house he and his wife own in Henderson. It shows Roberts and six other New York-Presbyterian Hospital EMTs rushing toward the towers as they blazed.

According to Roberts, the rate of illness in those pictured is 100 percent.

"Jack Delaney, the guy in the white helmet and blue jacket, he has asthma and nodules on his lungs now," the 59-year-old says. "John Bergman, he has asthma. Tony DiTomasso, he's behind me. He's got asthma, too.

"The other guys, they're all on inhalers."

For Roberts, the horror began after a midnight shift in the pediatric critical care unit.

"I was exiting the hospital when one of the crews flagged me down and told me what happened," he remembers.

At least once a week, Roberts relives steering his ambulance down FDR Drive -- which was closed by police -- thanks to vivid nightmares.

"As a paramedic, I've had to scrape body parts off of frozen streets," he says. "You can deal with that, because that's what you're trained to do."

But nothing prepared Roberts for all the severed arms, legs and heads. (Both he and Quaranti say they have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.)

"It looked like somebody went to a meatpacking plant, got the waste truck and dumped it while driving down the highway," Roberts says. "I had to make the constant decision to drive over body parts."

Roberts had fewer hours of dust exposure than Quaranti. He left ground zero after 40 hours. But his team was exposed at a much more harmful time. It had just set up a triage area 150 feet from the south tower's foundation when the first loud rumble occurred.

"We started feeling debris hit our helmets," Roberts remembers. "Then someone yelled, 'It's coming down!' I looked up and there was this huge, gray-brown cloud above me."

Roberts ran several feet, then dove for cover and tried breathing.

"You couldn't," he says. "All we were breathing in was matter. You had to hold your breath. You had no choice."

Initially, Roberts considered himself lucky. The solid debris fell in a horseshoe pattern around where he and his co-workers dove.

"It piled up all around us, but not on top of us," he says.

Six feet away from him, MetroCare EMT Yamel Merino lay dead. She was struck and killed by an I-beam that Roberts saw barreling straight at him.

"For some reason, it didn't hit me," he says.

Roberts thought he had escaped with only the ankle injury that forced him off the job and onto Social Security disability in November 2001. (His constant reminder is the brace he wears everywhere but to bed.)

But chronic asthma materialized in 2003, after Roberts moved to the valley to be closer to his daughter.

"I actually thought I was having some kind of allergic reaction to something I'd eaten, because I was wheezing," he says. "And I don't wheeze."

Every morning, Roberts must now puff from inhalers of Symbicort, Xopenex HFA, Spiriva and Azmacort, which he also inhales three more times per day. The steroids have puffed up his face.

"I never looked like this," he says.

The 9/11 attacks caused one of the most dangerous atmospheric conditions ever recorded on earth, according to Landrigan.

"There were extraordinarily high concentrations of toxic chemicals," he says.

The initial cloud, 75 percent of which he says consisted of pulverized concrete, was highly alkaline.

"It was like inhaling powdered Drano," Landrigan says. "And the reason we've had so much disease of the lungs is that this incredibly toxic stuff seared and burned the inner lining of the lung."

Thomas Cahill, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of California, Davis, has published some of the most comprehensive scientific studies of ground zero toxins. He says Quaranti and Roberts probably also inhaled lethal metals such as lead (from computer terminals) and mercury (from fluorescent light bulbs).

"And those were all ultrafine particles that penetrate deep in the lung and work their way into the bloodstream," he notes.

Cahill says that exposure probably would have rendered their bodies "much more vulnerable" to heart attacks, in addition to further lung disease.

And Cahill's studies didn't even specifically examine the reported 400 tons of asbestos with which the towers were fireproofed.

Quaranti breathes as deeply as he can.

"You hear it?" he asks.

The clicks of mucus in his chest seem lower in volume.

"It's a little better than it was before, right?"

Quaranti has spent the past eight minutes desperately sucking albuterol mist through a tube connected to the nebulizer machine on his coffee table.

Until he performs this ritual every morning, he describes the feeling in his chest as "like if you're underwater holding your breath and you just can't hold it anymore."

On Sept. 13, the all-clear was given by both New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani and the Environmental Protection Agency.

"The air is safe as far as we can tell," Giuliani told the New York Daily News, "with respect to chemical and biological agents."

"Just looking at it, you knew it wasn't safe," Quaranti recalls. "You could tell something wasn't right with it. From the fires that were burning, I remember seeing a lot of green smoke. I didn't know what it was, but I never saw smoke like that."

Quaranti was issued a disposable dust mask on Sept. 12.

"That's basically the equivalent of a fashion accessory," says David Newman, industrial hygienist for the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health. "Right off the bat, when you have asbestos present, there are safeguards legally limiting you to specific types of respirators. And in no event is a dust mask a respirator. It provides zero protection whatsoever.

"And both the city of New York and the appropriate enforcement agencies would have been intimately familiar with that."

For Quaranti, the coughing began almost immediately.

"You would think maybe it was the flu or something like that," he says. "Then, as time went on, I noticed that I would tire easily. I didn't feel as strong as I did.

"But I just figured, I'm getting old. Who knows?"

Eventually, Quaranti received a proper respirator, a GME-P100, manufactured by Mine Safety Appliances. It's part of his 9/11 garage tour.

It wasn't issued until Nov. 13.

"That's unacceptable," Newman says, adding that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration "very deliberately and consciously opted -- at that point in time, and over the following 10 months -- not to enforce applicable standards."

Congressman Jerrold Nadler, D-N.Y., whose district includes ground zero, notes that no first responders at the Washington, D.C., attack site got sick.

"There was air pollution at the Pentagon," Nadler says, "but they enforced the OSHA laws there. Here, they made a decision not to."

According to Nadler, health issues in New York were trumped by political ones.

"This was a conspiracy -- by the federal administration and the Giuliani administration -- to open up Wall Street and to try to show that the economy was getting back together as fast as possible," he says, "no matter what the health or life consequences.

"The people were expendable."

In response to the accusations made by Newman and Nadler, OSHA spokeswoman Sharon Worthy e-mailed the transcript of former OSHA regional administrator Patricia Clark's sworn 2007 testimony before the House Committee on Education and Labor, which stated that OSHA distributed more than 131,000 respirators during the 10-month cleanup. Clark also testified that air-quality samples showed exposure to asbestos, organic compounds and metals at "well below" OSHA's permissible limits.

In her e-mail, Worthy also states that "OSHA categorically rejects any allegation or insinuation of a 'conspiracy' to shortchange the health and safety interests of workers at ground zero."

Quaranti retired on his union's standard one-half pension in 2005. (He says his last year's salary was $100,000, including overtime counted in his pension formula.) He also receives Social Security disability.

"I didn't want to retire, but I wasn't feeling good enough," he says.

Initially, Quaranti didn't think he could qualify for disability from New York City.

"I didn't know if I was bad enough at the time," he says, "and I didn't really want to fight the city. I didn't have the energy."

In 2006, New York Gov. George Pataki signed legislation allowing uniformed municipal workers sickened by 9/11 to leave their jobs on three-quarters disability. In August, Gov. David Paterson expanded that legislation to grandfather in those who retired beforehand, only to become ill later.

"I'm in the process of getting that going now," Quaranti says. "We'll see how that works out."

Responders who worked for private companies were not necessarily as fortunate.

Roberts collects $1,900 a month in Social Security disability, and $400 a week in workmen's compensation from New York-Presbyterian. Those checks will continue coming for the rest of his life.

"Everybody says, 'You're doing OK,' " Roberts says. "But you don't understand. If my wife wasn't working, we'd be in a little small apartment somewhere."

When he went on disability, Roberts says his annual salary was $108,000. With overtime right now, he estimates it would exceed $150,000.

"To be honest with you, I'm not being compensated enough," he says.

Neither Quaranti nor Roberts received additional money from funds or charities that collected money for 9/11 victims.

The good news is that both have full health coverage, through a combination of their retirement and Social Security programs. According to Landrigan, 40 percent of first responders are uninsured.

"And another 30 (percent) to 40 percent have health insurance that fails to cover many of the conditions they have developed since 9/11," Landrigan adds.

Roberts prepares for the swim his doctor recommends for his ankle each morning. He removes his ankle brace and lowers himself into his backyard pool.

"I'm worried about what might happen next," he says while floating on his back.

Last year, Roberts was hospitalized four times with asthma attacks. Each time, his blood oxygen saturation, which should be between 98 and 100, dipped into the 80s.

"That's dangerously low," he explains.

According to Roberts, being a medical professional is as much a curse as a blessing when illness strikes.

"A little knowledge can be dangerous," he says, "because we know how bad it can get. You can have a turn for the worse at any time."

Roberts redirects the conversation toward his hobby: music.

"When I was a kid in the '60s, I played in a lot of rock bands," he says.

Once a week, Roberts drives down the hill into Las Vegas, to Kathleen Perry Vocal Studios, for singing lessons.

"Who knows?" he asks. "I could still end up being an old-fogey rocker."

Roberts no longer has a band, nor any prospects for a live gig or recording deal. Often, his asthma gets so bad, he has to cancel his lesson.

"But it's just something to do," he says. "You have to keep your mind busy, or you think about things that you don't want to think about."

Contact reporter Corey Levitan at clevitan@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0456.

ON THE WEB Video SlideshowSEPT. 11 MEMORIALS Las Vegas firefighters will pay tribute this morning to the 343 New York City firefighters who were killed on Sept. 11, 2001, while responding to terrorists attacks at the World Trade Center. At 6:45 a.m., they plan to gather at the flag poles at each fire station while dispatchers sound three bell tones over Las Vegas Fire and Rescue’s communications channel. The observance will launch a series of tributes and memorial services that will end with a candlelight vigil sponsored by the Metropolitan Police Department at the Clark County Government Center, 500 S. Grand Central Parkway. The police department’s memorial service begins at 6:30 p.m. in the amphitheater and is open to the public. Sheriff Doug Gillespie will deliver the keynote address and the Palo Verde High School choir, Vocal Infinity, will perform. The event will also feature posters from several elementary schools to memorialize the 2,819 people who died . At 7:15 a.m., Palo Verde High School will hold its annual tribute for Barbara Edwards, a teacher who was killed on American Airlines Flight 77 when it crashed into the Pentagon. Another Las Vegan, Army Lt. Col. Karen J. Wagner, was also among those who died at the Pentagon . Flags at all state buildings will fly at half staff today for what Gov. Jim Gibbons has declared Patriot Day 2008. REVIEW-JOURNAL