Tuskegee airmen fought war, segregation

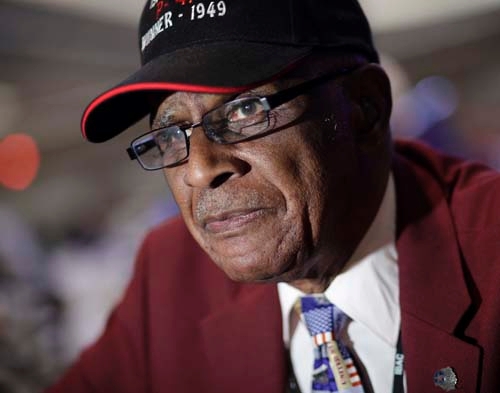

"The last hurrah" for the Tuskegee airmen, as retired Lt. Col. James H. Harvey puts it, was the 1949 gunnery meet at what was then called Las Vegas Air Force Base.

One month later, in June 1949, desegregation took hold and the elite group of black pilots and support crews that had been formed as a World War II experiment was broken up and sent to different units in the United States and overseas.

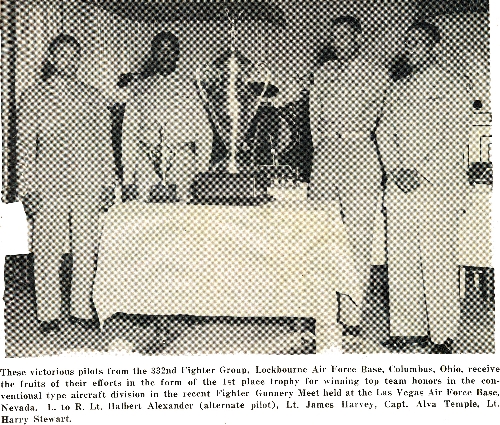

During last week's International Black Aerospace Council convention, Harvey, 89, talked about the little-publicized competition and the team of Tuskegee pilots who flew obsolete, propeller-driven P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes. The team outperformed 11 other Air Force "top gun" teams flying cutting-edge aircraft and won the trophy for a series of aerial bombing, strafing and rocket-firing events at what is now Nellis Air Force Base's Nevada Test and Training Range.

But when it was over and another pilot nosed out Tuskegee's team leader, Capt. Alva Temple, for the top individual honors - "I personally think they gave him (the other pilot) extra bullets," Harvey said - the team trophy was tucked away inside an Air Force warehouse in Ohio. Forty-six years later, in 1995, a search located the trophy, which is now displayed at the U.S. Air Force National Museum at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

"They just didn't want anyone to know we won the weapons meet," Harvey said Thursday at the Las Vegas Hotel, where Tuskegee Airmen Inc. held its 41st convention in conjunction with the Black Aerospace Council.

"They just didn't want the public to know about the Tuskegee airmen and how good we were," he said.

Like most other groups of World War II-era veterans, the ranks of the 992 pilots who trained at Alabama's Tuskegee Army Airfield in the 1940s have dwindled to dozens. Only 38 Tuskegee airmen attended last week's convention.

Harvey, of Denver, and two other retired Tuskegee lieutenant colonels from Phoenix - Robert Ashby and Asa "Ace" Herring - spoke about the battles they fought at home and at the onset of their 20-year Air Force careers to overcome segregation and so-called Jim Crow laws while about 450 of their colleagues fought in Europe and North Africa. It was this four-squadron group based in Italy that inspired the recent movie "Red Tails."

They said the movie has made more people aware of the World War II accomplishments of the Tuskegee pilots who escorted bombers into the teeth of battle with Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler's Luftwaffe. The strife and discrimination on the home front, however, has faded into history.

"We felt dejected, and certainly we didn't enjoy the discriminatory practices that were prevalent during that era," said Herring, 86.

"We didn't have the opportunities that some of the others had, and the training was more than the usual for a pilot," he said.

Ashby, 87, summed up life at Tuskegee Army Air Base in light of Jim Crow laws of the deep South.

"We had to obey the law," he said. "We had separate drinking fountains, separate eating facilities, separate clubs.

"We did not socialize together. The entire base was segregated. After it got to such a tension that the base was going to explode, they got rid of this commander and brought in a new commander, Col. Noel Parish. He did away with all the segregating activities, and every one ate, worked, socialized and did everything together."

After they were intensely trained in a flight school that was designed for them to fail, they overcame the odds and were eager to demonstrate their skills on the battlefield. But their chances slimmed as the war wound down.

Harvey had just completed combat training in South Carolina and was waiting for his deployment orders.

"I got a message to hold because the war in Italy was over. I was disappointed," he said. "I had heard Hitler heard I was coming so he threw in the towel."

In fact, a month later the war in Europe ended, and then Japan surrendered about three weeks after U.S. aircraft dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 .

As more military personnel were being discharged, the color barrier became a bigger hurdle to overcome for blacks to find jobs in the private sector.

"Segregation. That was the main thing," Ashby said. "They were not hiring pilots. Right after the war we had about 600 pilots out there trying to get a job, and they would not hire one of them."

While many Tuskegee airmen, like Herring, left their military careers to continue college, some, like Ashby, opted to stick it out.

Ashby was deployed for the occupation of Japan. Despite his proficiency in several different types of aircraft, he was taken off flying status and assigned to a quartermaster depot.

In a word, it made him feel "lousy." After three years in Japan he returned to Lockbourne Army Airfield in Ohio and joined the 332nd Fighter Wing.

About that time, on July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman signed an executive order that prohibited discrimination and mandated equal opportunity and fair treatment for all personnel in the armed forces.

Herring recalled his feelings. It was a step forward "but that's just a piece of paper."

"It doesn't change the hearts and minds of the people, and therefore, it was a gradual change. Even today people speak of equal levels of a playing field. But I always say, it's not a playing field. It's not a game. It's a matter or life or death, or a matter of survival," he said.

Because of previous events and acts of resistance against discrimination at Tuskegee Army Airfield, the Tuskegee airmen became the forerunners of the civil rights movement. They paved the way for a woman from Tuskegee, Rosa Parks, to refuse to obey a Montgomery, Ala., bus driver in 1955 who told her to give up her seat to a white passenger.

Said Ashby: "I would say the greatest contribution we made to this country is we integrated the military of this country."

Ashby served 21 years in the military including a stint in the Korean conflict with the 3rd Bomb Wing, as did Harvey who flew 126 missions in F-80 Shooting Star jets.

After Ashby retired from the Air Force, he flew in the commercial airline industry, first as a flight operation instructor with United Airlines and later as a pilot with Frontier Airlines. He became the first and only documented Tuskegee airman to also make a career as a commercial airlines pilot.

After college, Herring continued his 22-year Air Force career training foreign NATO pilots and becoming the first black squadron commander at Luke Air Force Base, Ariz., in charge of the 4518th Combat Crew Training Squadron.

He also served in the Vietnam War as deputy director of a ground-support air center. By that time in the 1960s his race "was no problem whatsoever."

"If you're in danger, you don't care what color the guy is, what religion, sexual orientation or anything else. You're in battle together," Herring said.

He said while anti-discrimination laws have helped erase racial barriers in America, getting to know each other as individuals has done more to shape equality.

"If you live together, you work together, you fight together and you die together; that's going to change a lot of hearts," Herring said.

Ashby's advice is "to keep moving forward."

"There's a big expression going on in political fields now, 'Take the country back.' I'm not going back. I'm going forward."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.