With wife’s donation, kidney recipient finds donor on exchange chain

Norman Castellanos smiled broadly as he talked about dying. His wife, Amabilia, and daughter, Daisy, with him at his hospital bed at University Medical Center, smiled right along with him.

Castellanos was recovering after receiving a kidney donation four days earlier. Thousands of people receive kidney donations every year but his was unique, and the first of its kind in Nevada. He was part of a relatively new way to find donors, known as a kidney exchange chain. It involved his wife making a kidney donation to a stranger, and the chain -- involving multiple donors -- traversed the country.

The 65-year-old former carpet cleaner at MGM and delivery truck driver said what he once saw in his future was the tortuous end that comes to so many whose kidneys have failed.

Until his body finally couldn't take it anymore, he said, he would have had to endure the agonizing side effects that come from a dialysis machine slowly vacuuming his blood clean three times a week: dizziness, cramps, vomiting and fatigue so debilitating that getting out of bed feels like a hard day's work.

This, he said, seemed a certainty when neither his wife nor other willing family members were compatible living donors. Either their blood type or their health problems stood in the way of a transplant.

"It didn't look good," said Castellanos, who suffered kidney failure in 2008 because of high blood pressure and diabetes. "I figured I knew what was coming. Four thousand people a year die waiting for transplants. I'm sure glad I was wrong. I feel great already. It's like a miracle."

That miracle happened when Norman and Amabilia became part of living donor chain that began in New York in 2009 and ended in San Francisco this month. The chain facilitated 12 transplants at seven medical centers across the country, including the Mayo Clinic, UCLA, Cornell and, for the first time, UMC.

It tied four other kidney transplant chains as the longest in the world, according to Gil Hil, the founder of the National Kidney Registry and the man most responsible for turning the donor chain concept into a workable reality two years ago.

A kidney chain, first developed by Gil to aid his own 10-year-old daughter, is designed to overcome the biggest roadblock to life-saving transplants: donors who do not match the tissue or blood type of a loved one who needs a kidney.

The registry compiles these unmatched pairs into a pool, finding the right donor for the right recipient. Cecile Aguayo, who recently became the UMC kidney transplant coordinator, had worked with the donor chain concept in Utah and brought it to Nevada.

"It has the potential of saving so many more lives of people who need transplants," she said recently as she sat in her office. "We have hundreds of Nevadans waiting for transplants."

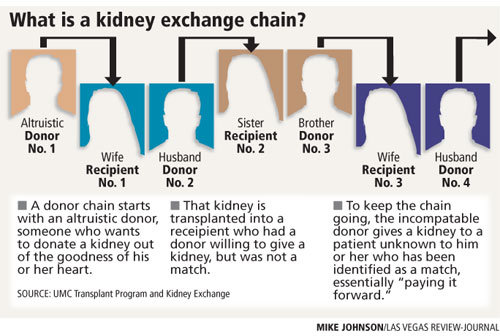

Armed with diagrams, Aguayo showed how the donor chains work.

Always, she noted, they start with a prototypical good Samaritan -- someone willing to give up a perfectly good kidney for altruistic purposes, making the first match with a recipient who is a complete stranger.

That stranger's friend or relative donates to another matching but unknown recipient, and the swaps continue -- an outpouring of kindness with each donor paying the gift of a kidney forward.

Aguayo had called a number of Nevadans who had earlier volunteered to donate kidneys to loved ones or friends but had been turned down because of incompatibility. She explained to them that although they couldn't be part of a direct donation, it was possible they could still donate an organ that would enable their relative or friend to get a transplant.

Only 50-year-old Amabilia, a maid at New York-New York, immediately wanted to be part of it.

"When I heard if I donate kidney to a stranger, my husband would get one, I want to do," the immigrant from Guatemala said in halting English as she held her husband's hand. "This way, I get to help more people."

Last Monday, four days after she had a kidney removed at UMC that was flown to save a dying man in San Francisco, Amabilia Castellanos, her makeup done just so, said she was ready to go home and to work at New York-New York.

"No, no, you need more rest," said her husband, who hopes to return to truck driving in a year.

On Tuesday, the Castellanos, who have been married 20 years, both went home.

Gil and Aguayo both believe the reason more people aren't taking advantage of kidney exchange chains across the country is that too many patients give up hopes of a transplant after relatives or friends are found not to be a match.

In the last two years, just over 100 transplants have occurred through kidney exchange chains.

In a phone call from New York, Gil said the program has the potential of going worldwide. The bigger the pool of potential donors and recipients, he said, the better.

"Our computers can now do the matching in minutes," he said.

"We're just starting this in Nevada," Aguayo said. "And we definitely want people to take advantage of it."

Not everyone can be a potential donor. It took a couple months of medical testing before Amabilia Castellanos was cleared.

Once the Castellanos' data was entered into the National Kidney Registry computer, it was a matter of days before the right chain was found.

Aguayo and coordinators from two California medical centers started working on the logistics to make three donations happen on Feb. 18.

On that morning Amabilia Castellanos had a kidney removed which was flown to the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, where it was implanted into a male patient later in the day. Within hours, the daughter of that recipient donated a kidney to a woman in San Francisco.

That afternoon Norman Castellanos received a kidney that had been surgically removed from a woman at UCLA. She had donated a kidney because her husband received one a week before from a New Jersey man.

Dr. John Sorensen, head of the UMC transplant surgical team, did the procedures on both of the Castellanos. He completed both in less than four hours.

"There were no problems at all," Sorensen said. "Mr. Castellanos' kidney started working right away, and his wife tolerated the procedure very well."

Aguayo said it isn't always easy to keep things running. Organs are delivered by commercial airlines, she said, so coordinators always have alternate flights or methods of transportation scheduled in case of scheduling glitches.

"The logistics can get pretty difficult. You have to deal with the weather and plan accordingly. You have to get organs on and off planes in a timely fashion."

She referenced a potential complication, that of President Barack Obama's Feb. 18 trip to Las Vegas. "We were worried (his) plane might tie up the airspace so we wouldn't get Mr. Castellanos' kidney on time, but fortunately it came in on an earlier flight."

Though it's rare, donors occasionally have backed out of surgery as they are being prepared for their operations, she said.

Still, Aguayo said any problems arising while making kidney donor chains work are far outweighed by the good they do.

She can rattle off statistics that are daunting: In 2008, there were more than 80,000 people on the official waiting list -- including 220 Nevadans -- and only 16,517 got transplants.

In the last three years, around 12,000 people have died waiting for a kidney transplant.

Nineteen-year-old Daisy Castellanos says the program shows both the wonders of modern medicine and the power of love.

"I was worried when my parents were both being operated on the same day, but everything turned out so great," she said. "I knew my mother loved my father, but now I know she loves him more than I ever knew. And she did it by giving a stranger hope, too. Like the doctor said, she's a hero."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.