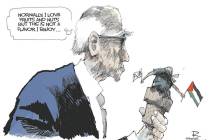

COMMENTARY: New pot edict makes its use a gamble

Prohibition-lite: That’s President Donald Trump marijuana policy set out last week in Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ guidance to U.S. attorneys, encouraging them to enforce federal pot laws even where states have legalized the drug. This is a reversal of President Barack Obama’s approach, which tried to impose some logic on law enforcement policy by discouraging federal charges.

The effect of Sessions’ move is to make the law into a roulette game, with luck determining who gets prosecuted and who doesn’t. And that in turn undermines the rule of law itself, which thrives on regularity, predictability and treating like situations and people alike.

To be sure, there’s nothing legally inappropriate about the new Department of Justice guidance. Federal laws that criminalize marijuana remain on the books. The president has a constitutional obligation to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” In that sense, it is perfectly reasonable for the attorney general to say that federal officials may, at their discretion, bring charges for violation of federal marijuana laws.

Using that logic, Sessions’ statement made the point that “it is the mission of the Department of Justice to enforce the laws of the United States.” Sessions also criticized the Obama policy, saying that “the previous issuance of guidance undermines the rule of law.”

That’s not absurd. It could be argued, along Sessions’ lines, that the Obama approach of holding back from marijuana enforcement was a policy in search of a constitutional justification. True, the president has discretion to choose prosecution priorities. But this discretion must have some stopping point.

Several federal courts suggested as much when they blocked the Obama immigration policy known as Deferred Action for Parents of Americans, which would have protected from deportation certain undocumented immigrants who are parents of U.S. citizens. The constitutional problem with that plan was, according to those courts, essentially that the president was subverting laws passed by Congress in the formation of policy.

Obama did garner some implicit legislative support for his approach to pot. The Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment, passed in 2014, prohibits the Justice Department from using its resources to enforce federal marijuana laws against medical marijuana authorized by states. That law signals Congress’s support for the allowance of medical marijuana use, even if it falls short of actual authorization. The amendment has been renewed each year since.

What was good about the Obama policy, then, was not its relationship to federal law, which it to an extent contravened, but to state law, to which it deferred. The whole logic of the Obama policy was that it would not act against states that had legalized pot for medical or even recreational use. Instead, the Department of Justice would allow itself to be guided by state law, whatever it might be.

The effect of the Obama policy was thus to reduce the illogic of state legalization being contradicted by federal prohibition. In this sense it was a blow struck for federalism and recognition of the democratic will of the states that voted for legalization.

The effect of the Trump policy is to do the opposite. It tells the states that they are not free to do what they want about marijuana — or at least that is the rhetorical effect of the announcement.

In practice, it is almost inevitable that renewed uncertainty about whether pot is going to be prosecuted will hamper the growth of the corporate cannabis industry.

That’s not the end of the world, economically speaking. To be a bit more precise, uncertainty about prosecution will discourage corporate actors who have a high degree of risk aversion from entering the market. The cannabis industry in particular is well-versed in managing uncertainty. Some market participants started in the industry when it was completely illegal. Others have been operating through years of gray-zone norms.

As a matter of market logic, legal uncertainty is likely to raise marijuana prices for consumers. That’s not such a disaster, either.

What’s bad about the Trump policy is that it renews and embraces the situation where anyone who grows, sells or buys marijuana must rely on luck in trying to figure out if the act will be prosecuted. It’s one thing to take risks when you know your action is against the law. It’s another when your state is telling you your action is legal and the federal government is telling you it isn’t.

The checkerboard legal situation encourages structural disrespect for law itself. The rule of law flourishes when we know how we will be treated by actually existing legal institutions. It erodes or fails when we can’t be sure.

One of the bad side effects of Prohibition was that the law was violated broadly and systematically, and enforced almost arbitrarily. Most historians think this had a bad effect on rule-of-law values.

Trump’s Prohibition-lite leaves it to individual U.S. attorneys to decide whether they want to be Eliot Ness. There will be no simple way for the public to guess where and how enforcement will be strict, and where the Obama directive will continue to be followed in practice.

It would be too easy to dismiss the Sessions announcement as mere words. These words have consequences for law itself.

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg View columnist. He is a professor of constitutional and international law at Harvard University and was a clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter.