EDITORIAL: The nation’s K-12 establishment sending too many unprepared kids to college

Perhaps the most striking example of educational malfeasance at the K-12 level may be found in our nation’s colleges and universities. That is where thousands of young adults who were handed high school diplomas discover they aren’t prepared for college-level work and must enroll in remedial courses.

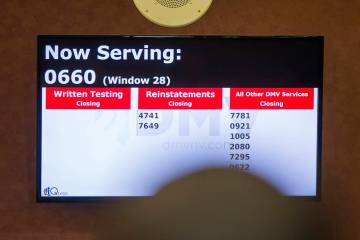

In Nevada, for instance, 57.7 percent of Class of 2014 grads who continued their studies in the Nevada System of Higher Education required remediation in either English or math. That’s up from 54.9 percent the previous year.

The problem isn’t unique to the Silver State. The Wall Street Journal reported this week that such classes cost students and schools “roughly $7 billion each year.” Community colleges, in particular, struggle with students who lack basic skills.

In addition, the lack of preparedness is also a strong indicator of whether a student will ever attain a degree. The Journal reports that the six-year graduation rate for students who entered the California State University System in 2009 and didn’t need remediation was 66 percent. The number dropped to 45 percent for kids shuffled into refresher math and English courses.

Why universities — particularly some with high academic standing — grant admission to students unprepared for the rigors of higher education is a valid question. Suffice it to say, however, that a confluence of factors — economic, political and social — make it unlikely that university systems as a whole will become more exclusive in their admission practices.

As a result, “the push to shake up remedial education has been gaining momentum across the country as universities struggle to improve anemic graduation rates,” the Journal notes. For instance, the California state system — along with schools in Indiana, Colorado, Tennessee, West Virginia and Florida — are experimenting with a more targeted approach tailored to student needs.

Instead of broader remedial classes in math and English, which are often taken for no credit, some states and schools now offer “basic skills” classes for which students earn credit and take alongside traditional college courses, the Journal reports. The goal, the paper reports, “is to help fill in the holes for less-prepared students who need it.”

A study at 13 Tennessee community colleges found the approach more successful, according to the Journal, but it also “requires substantially more resources.”

In the end, however, while these tweaks and experiments may lead to improvements, they do absolutely nothing to address the systemic issue: The nation’s hidebound K-12 education establishment — so resistant to reform for so long — is deceiving far too many parents and students into believing it has done a job that it has wholly failed to do.