Sidestepping studios to bring ‘Atlas Shrugged’ to the big screen

Ayn Rand attempted something so massive in "Atlas Shrugged" that, for 50 years, no one could figure out how to film it. And I don't mean just that it's a thousand-page book.

Growing up in Russia, Rand saw how socialism could destroy not just an economy, but the moral framework of a nation. She fled to America and promptly saw the same seductive culture of looting taking root here in Roosevelt's cynical "New Deal."

What Rand's brilliance illuminated was the critical realization that, as bad as the looters and redistributors are, they prevail only by insidiously recruiting their very victims to become "enablers."

She saw how America treats a self-made man who says, "I'm proud of my wealth; it's the creation of my brilliance and the sweat of my brow, and I don't owe you any of it."

The posturing parasites of "the state" -- abetted by the media and government-run youth propaganda camps -- droningly propagandize that the producers are greedy profiteers with no conscience. As a result, taxes and regulations multiply, sapping the producers' vigor and wealth, all under the guise of "making them pay their fair share" and "spreading the wealth."

The end result? With all the incentives for hard work, productivity and creativity drained -- while we perversely reward envy, sloth and a sense of "entitlement" -- we get a whole bunch of the latter, and ever less of the former.

The challenge of filming "Atlas Shrugged" is to take an audience who expects the "greedy fat cats" to be the villains -- and those cutting them down to size to be Erin Brockovich, Woodward-and-Bernstein-style heroes -- and get them to accept the role reversal and ask, "My God, what would happen if these long-abused producers simply went on strike and refused to be harnessed beasts of burden for the Great Collective?"

The book makes the point with lengthy speeches, anecdotes and monologues. But movie audiences expect action, romance, a machine-gun pace.

Talking heads droning on and on? That sound you hear is the crowd stampeding for the exits.

Successful corporate executive and poker champion John Aglialoro believed a 54-year-old book that still sells 100,000 copies a year, that ranks second to the Bible in polls of "books that have changed my life," could be filmed "straight."

His 20-year option on the rights was about to expire. No studio would join him in producing the film. So last year, he did it himself. The film opened this weekend nationwide.

Make room for Schilling

Produced by Aglialoro and Harmon Kaslow, directed by actor and former Olympic basketball player (OK, Canadian) Paul Johansson from a screenplay by Brian Patrick O'Toole, with surprisingly stirring music by Elia Cmiral, the movie is billed as "Part 1" of a trilogy-to-be.

The questions that arise are: a) Is this good enough to be considered a "real movie?" b) Is this Rand's book? c) Is it great?

Objectivity may be hard to find. After writing a fairly even-handed April 10 cover story on the guerrilla marketing techniques being used to get "Atlas" into mainstream movie houses, Rebecca Keegan of the Los Angeles Times "emailed us that the response has overwhelmed her," co-producer Kaslow told me Tuesday from Washington. "She says she's gotten an email from every Randian and from every one of the people who hate the book, and it's all in capital letters, people yelling at her."

In brief, yes, this is Rand's book. (At least, the first 319 pages.) The huge cast of characters has been trimmed a bit, to concentrate on the romance of railroad heiress Dagny Taggart and steel tycoon Henry Rearden. This allows a fairly rapid pace (broken only by the five-minutes-too-long "anniversary party.")

We're spared talking heads droning on about values and self-worth.

Instead, we get to see the war of the snarling anti-capitalist crowd, attempting to bring down the very builders of the prosperity they envy and covet, as they pass law after law requiring the rich to divest "all but one" of their companies, requiring every successful steel firm to share its profits with its less successful competitors. (General Motors bailout, anyone?)

The screenplay cleverly solves some obvious problems quickly. This is a story about railroads, quaint relics of the 19th century. What to do? The film's introductory montage explains that, in 2016, thanks to wars in the Middle East and a perverse domestic economic policy that's destroyed the value of the dollar (seem far-fetched, anymore?) gasoline is now $37.50 a gallon, leaving railroads the last viable way to move both freight and passengers.

Rand built books that were didactic. Her good guys are attractive, larger-than-life, and very, very good; her bad guys are unremittingly scurrilous. That doesn't leave a lot of room for subtlety. To call the supporting cast one-dimensional stereotypes is almost redundant.

The movie sometimes seems sketchy. In one vital scene, Graham Beckel, a tad over the top as oil giant Ellis Wyatt, visits Dagny as she drives her new rail line of Rearden Metal up the great Rio del Norte canyon, and comments that he was wrong about her.

There was a landslide along the route and Wyatt figured that would cause a month's delay. But Dagny had taken charge and cleared the route in mere days.

Pardon the cliche, but why tell us about it? Stage that scene with Taylor Schilling up to her boots and elbows in landslide dirt -- show us. This does seem to be a $5 million movie, shot on the fly.

In fact, some have argued this film exists only because digital filmmaking technology has progressed to the point where it enables a visionary with a few million bucks to sidestep the old Hollywood hierarchy and make films without the "permission" of the very politically correct cultural gatekeepers.

Yet the resulting "Atlas Shrugged" is, in the end, a pretty good movie -- a far more rewarding experience than 98 percent of the stuff out there -- maybe in part because, as director Johansson told one interviewer, he was raced into the project so quickly he "didn't have time to be afraid."

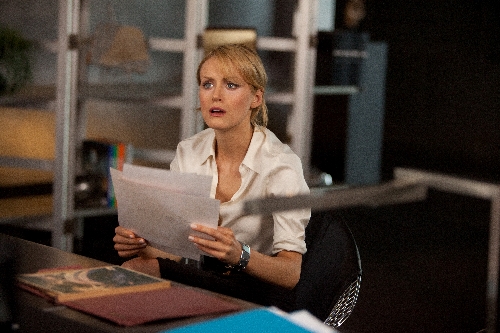

And the very best thing about this movie is the relatively unknown Taylor Schilling as Dagny Taggart.

The budget to hire the modern equivalent of Gary Cooper and Patricia Neal -- who starred in the last notable attempt to film Rand, "The Fountainhead," 62 years go -- wasn't there.

Instead, the film became Schilling's to own or to ruin. You can mark it on your calendar: April 15, 2011, is the date Taylor Schilling became a star.

The credit goes to "our casting director, Ronnie Yeskel," replies co-producer Kaslow. "At the moment we were casting the movie we needed credibility, and Ronnie brought that. She has the eyes for great talent. You're right, it's a once in a lifetime role. She (Schilling) came with a lot of courage and delivered a very compelling performance."

Popular groundswell

Why the low-budget production, followed by the guerrilla distribution campaign?

"We originally were hoping the movie would get produced by, you know, a studio," Kaslow replies. "Well, if they didn't want to produce it so they could own it, they didn't have an interest in distributing it."

Was the lack of interest due to the pro-capitalist theme, low-budget package or the fact it is "Part 1"?

"When they pass on a film they don't send you, they don't say, 'We don't like the politics.' ..." Kaslow said. "But John Aglialoro believed there was a population out there far in excess of the literary fans and the political fans, that would want to see this movie. When we started, they asked us, 'What can we do to get this movie into our cities?' So we created (online) technology to kind of track that interest. They wanted to talk directly to the exhibitors, so we gave them links to the customer service offices of these exhibitors.

"We didn't do anything nefarious; we didn't list any home numbers. AMC Theatres happened to be at the top of the list, because we did it alphabetically. Well, it started to cost them more than $2,000 a day to deal with all the interest in the movie. They asked us to direct people to a different site so it wouldn't cost them that money. So we did. And pretty soon they said, 'If there's this much interest in this movie, I guess we'd better book it.'

"We're now in all the major chains. It's not being released as an art-house movie. Originally we started with 11 cities. We're now going to have 299 screens" in more than 80 markets, Kaslow reported.

"That's phenomenal. People look at what we're doing and ask where are all the TV ads, where are all the radio ads? Our answer is this movie has community support." Thanks to the Internet, "We can speak with precision to the people who are interested in the movie. That's what's happening. Shows are beginning to sell out. It just seems like we've got sort of the right movie at the right time for the right audience."

The current film is "Part 1" of a trilogy?

"We've started to write the screenplay for Part 2; we're going to try to get it into production in June in order to be able to release Part 2 on April 15 of 2012, and then the third part on April 15 of 2013."

Will production of those parts depend on revenue from the first?

"John has the resources to do it. But if there's no audience for the movie, we're not on a mission to simply produce the movie simply for the sake of doing it. If there's commercial value we're going to take advantage of that. If people don't support it, there's no reason for us to throw money at it."

Kaslow said, "Right now it's about creating an accessible movie that captures the message of the book."

"Atlas" is playing at the Century 18 Sam's Town, Rave Motion Pictures Town Square, Regal Colonnade and the Regal Village Square.

Vin Suprynowicz is the assistant editor of the Review-Journal's editorial pages.