‘Worker centers’ allow unions to skirt law

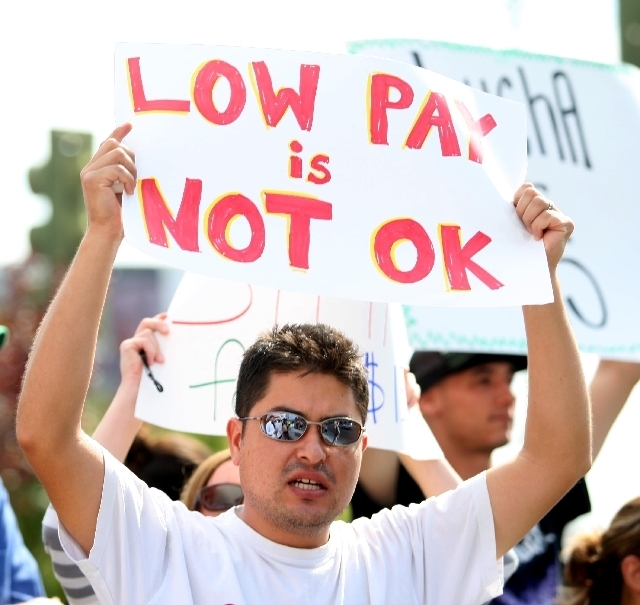

Organized labor kicked off its Labor Day festivities early this year, with a nationwide series of strikes at fast-food outlets and retail stores on Thursday. But while these pickets and protests are being funded by labor unions and led by union organizers, the organizations taking credit for the strikes aren’t technically labor unions at all — they’re actually labor union front groups that are exempt from federal labor law.

Welcome to the “worker center.” These clever organizations are the labor movement’s desperate attempt to stave off irrelevancy following decades of shriveling membership rolls, including last year’s loss of nearly 400,000 workers.

Labor leaders have succeeded in portraying worker centers as nonunion community groups that advocate for low-wage workers. Many of them are registered as charities, nonprofits and other tax-exempt entities. This legal loophole is the key to their existence.

It frees them from many of the regulations established in both the National Labor Relations Act and the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act.

But you wouldn’t know worker centers weren’t unions by looking at what they do. In practice, they organize paid picketers who protest and advocate in lockstep with their labor union parents for policies such as living-wage laws, mandatory paid leave and more.

In fact, the only major practical difference between worker centers and actual labor unions is that worker centers don’t “deal with” the employer through negotiations.

Instead, they use professional union organizers to single out a select group of employees with grievances — sometimes no more than a few dozen — and then engage in nuisance “strikes” and make demands of the employer that would apply to the entire workforce.

The ultimate goal, however, is still complete unionization — even when these protests start as a Potemkin village of strikers masterminded by union organizers.

Given these institutional advantages, worker centers have been created at an astonishing rate.

Starting with fewer than five in the early 1990s, the AFL-CIO now estimates that there are 230 such groups, with more added every year

These groups are active at both the national and local levels, including several in Nevada.

The headline-grabbing fast-food strikes are organized by “Fast Food Forward,” “Fight for 15,” and a host of similarly named organizations, most of which were founded and are funded by the Service Employees International Union.

There’s also “OUR Walmart,” which was hatched by the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union to target the big box retailer. Elsewhere, the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union helped found the Restaurant Opportunities Center to target high-profile eateries in major American cities.

Despite its long-standing ties to and its millions of dollars in funding for these groups, organized labor has only recently decided to admit its paternity. At its September conference, the AFL-CIO plans to formally recognize and incorporate worker centers in order to create “a new type of labor movement.”

It’s no surprise why labor leaders have resorted to this desperate tactic. Organized labor’s Great Depression-era structure is failing.

Its precipitous decline in members over the past seven decades — they’re at a 97-year low as a percentage of the workforce — has driven labor leaders to explore new paths to survival.

In other words, the worker center is organized labor’s “Hail Mary” pass.

Whether it will succeed remains to be seen. But while we wait to find out, the labor leaders behind these front groups need to answer one question: Why does organized labor’s brave new world need to be exempt from the regulations and the reporting requirements that were specifically designed to keep union activities fair and labor leaders honest?

Richard Berman is the executive director at the Center for Union Facts.