Spencer Haywood still paying for lawsuit that changed basketball

They warned him. But Spencer Haywood didn’t care.

His mom had been picking cotton in Mississippi since she was 3 years old. It was time for her to enjoy her life. So Haywood, a 6-foot-9-inch forward, sued the NBA in 1970 for the right to play in its league, even though he was still in college. At the time, a player wasn’t eligible for the NBA until he had spent four years in college.

But the NBA refused to budge, so Haywood fought, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. He claimed he was a hardship case and entitled to early entry. On March 1, 1971, the court agreed, ruling that Haywood was entitled to enter the league under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Basketball never would be the same.

Several generations of players owe thanks to Haywood for his courage to take on the NBA and pave the way for them to become multimillionaires earlier than they would have been entitled.

But that courage has come with a price. Curt Flood, who had fought baseball for the right to play where he wanted to, told Haywood his life would be hell for doing what he did. Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, heard the case and told Haywood afterward that he would be ostracized.

They may have been right. Haywood compiled a Hall of Fame-worthy resume during 14 NBA seasons — he averaged 20.3 points and 10.3 rebounds, was a two-time All-NBA first-team selection and a four-time NBA All-Star and won an NBA title in 1980. He also won an Olympic gold medal in 1968.

Yet, he still has not taken the call from the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

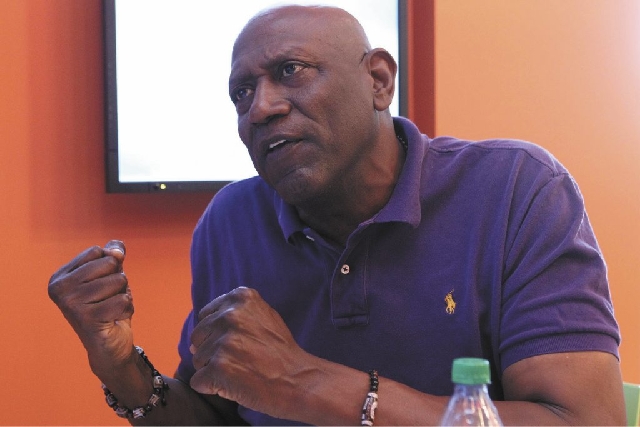

“I’m still suffering,” said Haywood, who lives in Las Vegas and owns a construction business. “If you look at all the things I did on the court, I would have been in a long time ago. But the (Supreme) court fight is the reason I’m not in. But I believe this is going to be my time.”

Haywood, 63, is one of 12 finalists, among them former UNLV coach Jerry Tarkanian and fellow Las Vegas resident and former NBA star guard Gary Payton. Speaking at the Discovery Children’s Museum, where his company installed the flooring and tiles in the bathrooms, Haywood talked candidly about his life — a life that was never about taking the safe route.

“It was that kind of time in American sports,” said Haywood, referring to the early 1970s, during which Flood challenged baseball’s reserve clause and boxing great Muhammad Ali fought for his right to refuse induction into the U.S. Army and not have to fight in Vietnam.

“Here’s the thing — I wasn’t looking for trouble. I just wanted to earn a living playing basketball. So when Seattle signed me (in 1970), and the NBA said I couldn’t play, I was angry. I couldn’t provide for my family. So I did what I had to do.”

With the support of SuperSonics owner Sam Schulman, who had signed Haywood to a $1.5 million, six-year contract, and a sharp legal team headed by Pete Brown and Al Ross, Haywood sued. But when he tried to play, he was served an injunction just prior to tipoff, and he had to leave the arena.

“The P.A. announcer would say to the crowd, ‘We have an illegal player on the Seattle roster,’ and that’s how I was introduced,” Haywood said. “Then I’d have to leave the building after they’d serve me with the injunction. I remember being in Cincinnati, and we were playing the Royals and I stood outside of Cincinnati Gardens in the snow waiting for the game to end so I could rejoin the team. I went through a lot of humiliation.”

But Haywood stood firm.

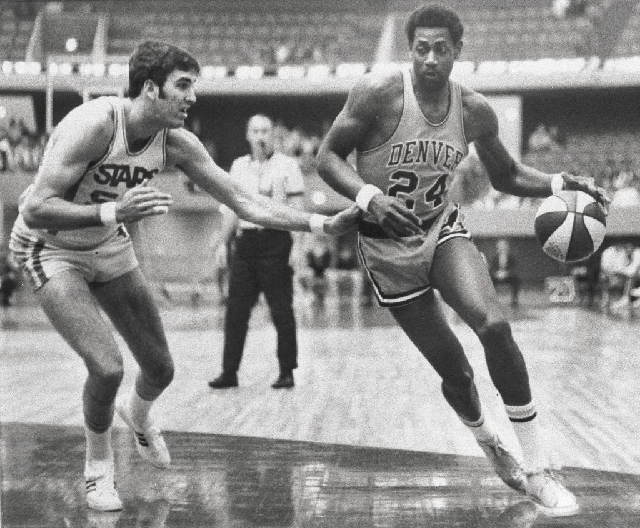

Along with the lawsuit filed against him by the NBA, the American Basketball Association was suing him for leaving its league. The ABA had allowed Haywood to enter the league after his sophomore year at the University of Detroit, and he had averaged 30.0 points and 19.5 rebounds for the Denver Rockets. And the NCAA joined the NBA’s lawsuit, because if Haywood won, the college game would take a major hit if other players decided to turn pro before their college eligibility expired.

“I was fighting a three-front war for a year,” Haywood said. “The NBA didn’t want me to come play in their league, the ABA wanted to keep me in their league, and the NCAA was mad because they knew they’d be hurt if I won.”

Haywood left Seattle in 1975 for New York, triggering a somewhat nomadic second half to his career. He played four years with the Knicks, and while in New York, he met and married supermodel Iman. He also played for the New Orleans Jazz and the Los Angeles Lakers, the team for which he won his championship. He ended his career with the Washington Bullets after the 1982-83 season — but only after he had played a season in Italy and was battling cocaine addiction.

“Have you seen that reality show on TV, ‘Basketball Wives?’ ” he asked rhetorically. “My life was a reality show long before that.”

Haywood and Iman divorced in 1987; they have one daughter. But he kicked his drug habit and rebuilt his life. He remarried in 1990, and he and his wife, Linda, have three daughters.

Yet, the ghosts of the past still seem to cling to Haywood. He said today’s players don’t seem to understand what he did in 1970.

“I’m still a pariah,” Haywood said. “I’ll be around Kobe, LeBron, Carmelo (Anthony) at USA Basketball camp and they won’t talk to me. What they don’t know, or want to know, is without me, there’s no them. But they’re in denial.”

Haywood could learn his fate as early as today. The Hall contacts inductees in advance of Monday’s official announcement in Atlanta during the Final Four.

“It will vindicate everything I went through,” he said of possibly getting the call after all these years.

Contact reporter Steve Carp at scarp@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2913. Follow him on Twitter: @stevecarprj.