State’s secure psychiatric hospital struggles with patient load

SPARKS

One patient rocks himself in a chair.

Others watch TV without much interest, while one woman flips through a book.

Some simply pace the halls to kill time, something you would see in any hospital. But this is Lake’s Crossing Center, Nevada’s only maximum-security psychiatric facility.

“Attention,” announces a man over loudspeakers shortly before noon on a late October Wednesday. “Those who take medication, please report to the Blue.”

Blue carpeting covers the floor of the nursing area where little cups — each a potpourri of pills — are tagged with a photo of the patient intended to take them. The faces are those of offenders with mental disorders sent there by the court system to be evaluated or for treatment to restore their competency to stand trial.

In Sparks, 450 miles northwest of Las Vegas, the call to medication is just part of a normal day for some of Nevada’s most dangerous criminals struggling with severe mental illness.

“You can only get here with a court order and get out with a court order,” Lake’s Crossing administrator Elizabeth Neighbors said.

The facility’s mission is to treat patients and restore their ability to participate in their legal cases, but the small hospital is receiving far more court-ordered patients than it can handle. It has only 66 beds to serve the entire state. All were full in late October, with women occupying about a quarter of them. About one in five detainees faces murder charges, some involving multiple homicides, said Lake’s Crossing correctional Lt. Michael Mason.

About 60 percent of the court-ordered patients are from Clark County. Small groups of detainees are flown to the Northern Nevada facility every two weeks.

Too many patients for too few beds isn’t a new problem for the secure psychiatric hospital. Eight years ago, Lake’s Crossing was sued over its patient backlog and now faces a second lawsuit over the same issue.

The facility operates under a provisional state license. Officials want it to be fully licensed in coming years as well as earn certification from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

IN MAXIMUM-SECURITY CARE

David Settle suffers from dementia and has brain damage, Clark County Deputy Public Defender Scott Coffee said.

In late December, the 68-year-old was found wearing only a diaper after police allege he hit both Henry Namett, 82, and Elenita Ablao, 59, in the head with a hammer more than 20 times at an assisted living group home on Washington Avenue, near Valley View Boulevard. He now faces murder charges, Coffee said.

“David Settle’s case was very unique,” Coffee said. “He acted out of character. It was out of character and strange enough and bizarre enough that just his facts determined he had to be evaluated.”

A court order filed April 23 sent Settle to Lake’s Crossing.

“At this point there’s a question as to whether or not (Settle) is ever going to be competent,” Coffee said. “But Lake’s Crossing makes that determination.”

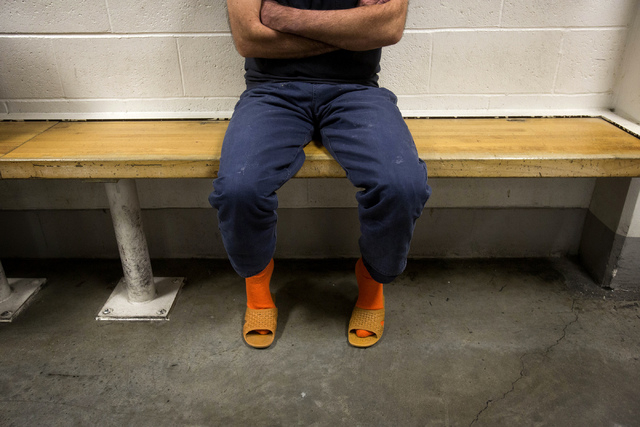

Most patients wear navy blue garb similar to prison uniforms, but some wear bright orange jumpsuits, signifying they are a high escape risk.

“A lot of these cases are the most tragic cases in the judicial system,” Coffee said. “A lot of times, what they do is directly related to their mental illness. Most of these people don’t see the world through the same lenses as we do.”

Charles Greco, 58, once was a Lake’s Crossing patient. About seven years ago he killed his 84-year-old father, Albert, thinking him to be the devil. News reports at the time say Greco strangled his father and mutilated his body with a butcher knife, severing his head and penis.

“When police came, he thought they were angels,” said Coffee, who represented Greco. “Charlie Greco is a good example of a tragedy of a mental illness.”

Greco suffered from schizophrenia for decades before the murder, Coffee said. Greco is now serving time at the Nevada Department of Corrections.

Mentally disordered offenders sent to Lake’s Crossing are usually in their 30s or 40s, Neighbors said. In the past, juveniles 15 or older who were of questionable competency and facing trial as an adult were sent to the facility, she said. The youngest detainee they have had was 15. The oldest was 88.

INCREASING DEMAND

Nevada established the facility following a 1972 Supreme Court decision that it is unconstitutional to commit mentally ill offenders to state prison for security reasons, or because they are criminally charged but found to be incompetent.

Funding came in 1973, and Lake’s Crossing was completed in 1976, according to Mary Woods, spokeswoman for the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. It has expanded repeatedly since then, along with increasing demand for its services.

Officials want to increase its staff of 85 to 110 in coming months, Neighbors said. The facility’s $10.7 million operating budget for fiscal year 2014 includes a 10-bed annex expansion at Dini-Townsend, a civil psychiatric facility on the same Sparks campus. The 10 beds will be used for Lake’s Crossing patients.

In fiscal year 2013, Lake’s Crossing’s operating budget was about $8.9 million.

Lake’s Crossing originally had 30 beds and has gone through three expansions. This past session, the state Legislature approved a 10-bed expansion that is expected to be completed by the end of November.

“This is a kind of issue that, without appropriate funding, is very difficult to solve,” Coffee said.

Lack of space has resulted in patient backlogs and legal challenges over the years.

“In 2005, everything was booming; Nevada was growing,” Neighbors said.

That’s when the Nevada Disability Advocacy and Law Center filed a lawsuit against the hospital over a significant increase in delays for admitting court-ordered detainees.

As part of a lawsuit settlement reached in 2008, Lake’s Crossing is supposed to admit detainees within seven days of a court order. The state hospital was able to comply until fall 2012, when it began receiving a higher number of detainees, a trend that has continued, Neighbors said. That created a backlog that prompted the Clark County public defender’s office to file a federal civil rights lawsuit on June 21, 2013.

The average wait time for detainees bound for Lake’s Crossing as of Nov. 1 was 85 days, and there were 49 detainees on the wait list, said Clark County Deputy Public Defender Christy Craig, lead attorney in the latest lawsuit.

The average wait time has dropped from a high of 99 days, she said. But detainees issued court orders involving competency issues on or after Nov. 1 now face a wait of 125 days.

Long delays create a number of issues, including lengthening the time it takes to resolve the legal case of a detainee whose competence is questioned.

“When they are totally incompetent they aren’t able to talk to you about their crime; they can’t tell you who was around; they can’t tell you where they were,” Craig said. “Some people don’t speak, and when they do speak, it is what they call ‘word salad,’ stuff that doesn’t make any sense at all.”

That means the investigation is stymied, witnesses can’t be located and no progress is made, Craig added. “The minute someone’s competency is in question, everything has to stop.”

The delay in being admitted to Lake’s Crossing also extends jail time for some detainees who could have been released much sooner, Clark County public defender Rafael Nones said. Some may actually be locked up longer than their sentence as they wait to be sent for treatment, go through treatment and are returned to their home community.

Lawsuit settlement talks are set for Wednesday in Reno, Craig said. The parties have already agreed on some issues, such as the need to renovate a Southern Nevada facility to duplicate Lake’s Crossing’s services by summer 2015.

A Lake’s Crossing task force, created after the first lawsuit against the hospital, began meeting again a few months ago. The group includes representatives from the hospital, the Clark County public defender’s office, the Clark County district attorney’s office, and NaphCare, the county detention center’s health care provider.

The task force, headed by Clark County District Judge Linda Bell, meets once every two weeks. They discuss detainees, including those who need to be sent to Lake’s Crossing quickly and those who are improving at the jail, Craig said. Every detainee is placed at the end of the list, but the task force can give priority to those who are severely ill.

“It’s a very cooperative group that has an impact on the waiting list,” Craig said.

WHY THE LOGJAM

State officials say a number of factors contribute to the patient logjam.

In 2001, Nevada reinstated the law allowing a defendant to be found not guilty by reason of insanity, Neighbors said. Defendants took advantage of it.

“We are beginning to see more and more of those pleas,” she said.

In 2007, a change in the law allowed the court to commit certain defendants to the hospital for up to 10 years if they are deemed dangerous and incompetent by the court, Neighbors said. These are individuals whose competency could not be restored and need to be treated in a maximum-security setting.

That includes offenders with any type A felony, such as murder, and some B felonies, such as voluntary manslaughter and battery with a deadly weapon. The court also must find them to be a danger to the community.

As of late October, seven patients at Lake’s Crossing fell under those two laws, Neighbors said. Two were committed after being found not guilty by reason of insanity, and five were found to be dangerous and incompetent.

Hospital officials also said they are seeing more patients with dementia. They should be in a secured nursing home, but there are few of those facilities, Neighbors said. So, “their stay extends.”

Transportation can also delay timely treatment.

Most criminals referred to Lake’s Crossing are from far-away Clark County, Neighbors said. “Transporting them untreated from the jails is an issue.”

Some detainees may have medical needs that Lake’s Crossing can’t meet, such as cancer treatment, so the hospital has to seek outside assistance.

The Metropolitan Police Department contracts with Vision Holidays for charter flights out of the North Las Vegas Airport. Every two weeks, five or six defendants are flown from Clark County to Lake’s Crossing, and the same number are flown back.

WAITING AT THE DETENTION CENTER

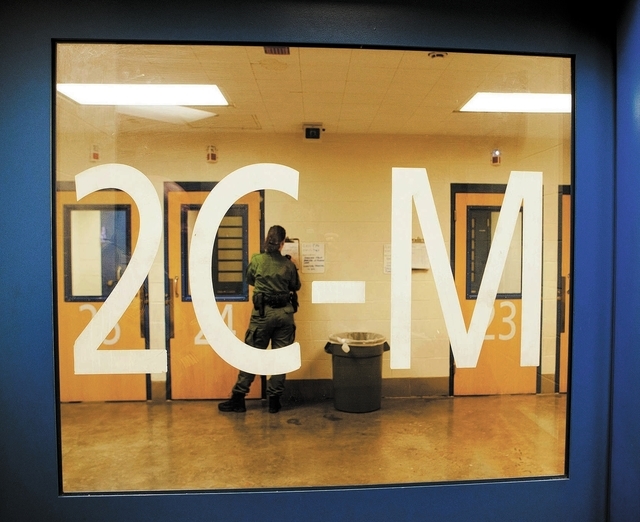

In the Clark County Detention Center’s wing for high-risk inmates, where some inmates headed for Lake’s Crossing bide their time, white dry-erase boards hung next to cell doors let jail personnel know what to expect. One recent Thursday, one note read, “Smear feces, spits, flooded room.”

On Nov. 7, correctional officer Armando Lozano told six detainees bound for Lake’s Crossing, “Nothing is going up with you,” as the men lined up against a wall before a van ride to the North Las Vegas Airport. Once there, the inmates were kept in the van while Lozano and correctional officer Rebecca Kelly placed “puppy pads” on each plane seat. Even though Sparks-bound inmates are routinely taken to the restroom before departing the jail, they sometimes urinate, defecate or vomit on the plane, Lozano said.

Lozano then called the detainees, cuffed at wrists and ankles, to board the plane one at a time.

“This is the hardest assignment,” Lozano said. “We are taking six unstable inmates on a plane. There’s a lot of potential for them to get out of control. It’s challenging. It puts all your officer skills to the test.”

Flights to Lake’s Crossing are already scheduled through March 6, 2014. Each round-trip costs about $6,800 for personnel, van and plane costs.

“There are people who go up there who don’t come back,” said Lt. Scott Zolman, who oversees the field services section at the jail.

From the beginning of this year through Oct. 31, the Clark County Detention Center transported 213 inmates to Lake’s Crossing, Zolman said. As of early November, 49 of the detention center’s 3,838 inmates awaited transport to Lake’s Crossing. About 24 percent of all inmates were on some type of psychotic medication, he said.

Many inmates with mental illness are housed in section 2ABG in the jail. Medical passes are done by medical personnel escorted by officers three times a day or more, Zolman said. It costs $142 per day to house an inmate regardless of their medical condition, he said.

The longest time a detention center inmate has waited for admittance to Lake’s Crossing is 163 days, Zolman said. The lengthy waits also are a problem for the crowded jail, especially in the special housing units.

This past legislative session, Sen. Joe Hardy, R-Boulder City, introduced a bill, SB 323, to have treatment to restore competency available at the jail. That would have eliminated the need to send detainees to Lake’s Crossing. The bill made it to the Senate Judiciary Committee, but died in the legislative process.

“I think there are things that can be done that would decrease the time and expense,” Hardy said.

Officials at the detention center supported Hardy’s idea, Zolman said.

OPENING A SOUTHERN NEVADA FACILITY

Renovations on a facility that will offer the same services as Lake’s Crossing in Southern Nevada could be completed in summer 2015, but additional funding from the Legislature will be needed to staff the hospital.

In late August, the Legislature’s Interim Finance Committee approved more than $3 million to renovate Stein Hospital, a closed mental health hospital on the campus of Rawson-Neal Psychiatric Hospital in Las Vegas. The facility will have 58 beds.

Forty-two of the beds will be for offenders with mental disorders. The remainder will serve as an overflow for Rawson-Neal, which recently was in the national spotlight for alleged patient dumping.

“I think we are going to see quicker turnarounds. People will be out of jail much quicker,” Craig said.

“It’s cost savings for the county, and it’s good for the defendants. … They are not just killing time at the jail. It has a huge impact, huge. We’ve been asking for it for years.”

But the challenges faced by Lake’s Crossing extend beyond litigation and crowding that could be alleviated by a second facility.

The hospital has never been fully licensed by the state, and it operates under a provisional license because the building doesn’t meet code requirements for a psychiatric hospital.

“When the facility was first built, there was a question as to what kind of facility it was,” Neighbors said. “Is it a detention center? Is it a psychiatric hospital?”

When officials applied to be fully licensed by the state’s Bureau of Health Care Quality and Compliance in 2008, issues arose.

The fire alarm system does not meet licensing or certification standards because it lacks a visual strobe alarm, Neighbors said.

The sprinkler system is not up to code, and several areas in the building don’t even have sprinklers.

In March 2012, another survey found similar deficiencies, as well as deficiencies with the facility’s doors and mantrap.

“The facility did not have a clear policy in place to address how the mantrap gate would be unlocked to complete exiting away from the building to an area of safe refuge,” according to documents from the state’s Bureau of Health Care Quality and Compliance.

“We have to be able to accommodate that, and we still need to maintain our security,” Mason said. “We are very concerned about maintaining security for the community. We need to make sure that people just don’t walk out into the community.”

But the facility does meet fire marshal codes, officials said, otherwise it wouldn’t be able to operate.

This past session, state lawmakers approved $3 million for renovations to address patient safety issues and bring the building up to code.

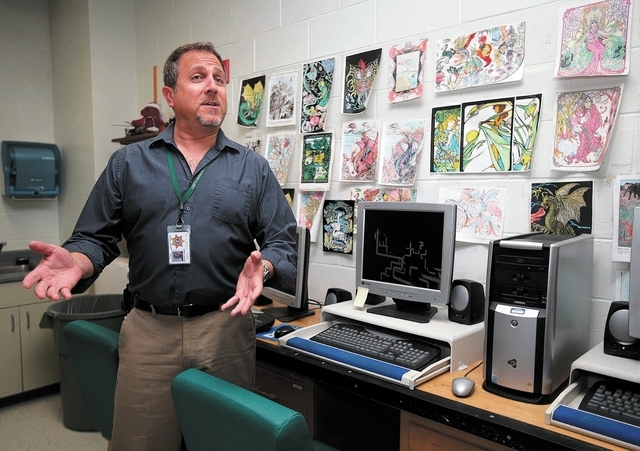

Other upgrades, such as replacing old carpeting and addressing issues in the control room, which has more than 72 cameras active 24 hours a day, will also be covered.

Officials expect those upgrades to be completed within two years, Neighbors said.

At that point, Lake’s Crossing will seek a full license.

If successful at doing that, officials will ask to be certified by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

In 2012, the facility had an exploratory review to see what the facility would “need to upgrade in order to participate” with the federal centers, Neighbors said.

Various issues were raised, including the lack of a medical director board-certified in psychiatry and failure to address priorities for improved quality of care.

The review also found the hospital lacked a policy or procedure to report deaths associated with seclusion or restraint, according to a 2012 review by the state bureau.

A few of the problems were corrected immediately, such as having a registered nurse in the annex at Dini-Townsend during day and evening shifts.

If certified by the federal agency, the hospital would be able to bill Medicare or Medicaid, Neighbors said.

“And it’s a good accountability process,” she said. “It’s another layer of assurance that people getting care here is up to national standards.”

Reporter Yesenia Amaro can be reached at 702-383-0440, or yamaro@reviewjournal.com.