U.S. dominated worldwide race

Imagine racing to Paris, France, from New York, N.Y., in midwinter by crossing the North American, Asian and European continents.

Now try to imagine that it's February 1908, and that you're preparing to embark on this daunting adventure -- in a windowless open-air touring car -- across the frozen, wagon-rutted American landscape that, until then, fewer than 10 souls had previously driven (and none in winter). And you're risking life and limb for nothing more than bragging rights and a commemorative trophy.

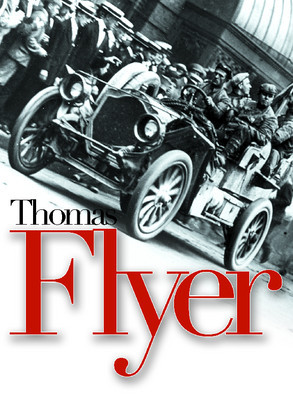

It was a herculean task presented to George Schuster, chief road tester for the Thomas Motor Co. His boss, Edwin Ross Thomas of Buffalo, N.Y., requested that he join the Thomas Flyer team in a New York-to-Paris competition, dubbed the Great Race. It was sponsored by the New York Times and Le Matin (Paris) newspapers.

The Flyer had been originally introduced in 1906 and retailed for $4,000 (the equivalent of about nine years wages for the average worker). By 1907, more than 1,100 Flyers had been produced, of which 400 served as taxicabs. The car's 60-horsepower four-cylinder engine could propel the Flyer to a top speed of 60 mph, although in those days only a few roads were in good enough shape to accommodate such speeds.

Although the 35-year-old Schuster was originally conscripted as the riding mechanic, he wound up piloting the Flyer after the original driver quit in San Francisco. Schuster's companions at various times consisted of a couple of assistants and a New York Times reporter assigned to cover the race and keep the newspaper's anxious readers abreast of the unfolding event.

The other Great Race participants consisted of a German and Italian team, plus three entries representing now-long-forgotten French marques. In fact, all of the vehicles, including the German Protos, Italian Zust, French Motobloc, DeDion and Sizaire-Naudin, as well as the American Thomas car firms are now just relics from another era.

Both sponsoring publications hyped the event to the max, billing it as a nation-versus-nation grudge match. All of this media focus generated enormous publicity for the participants and, not coincidentally, helped to sell plenty of newspapers.

On the morning of Feb. 12, 1908, the half-dozen racers and their respective crews roared away from the Times Square starting line and the Great Race was officially under way. A crowd estimated at about 250,000 people cheered them on, including Edwin Thomas, who honestly doubted that any of the contestants, including his key man Schuster, would make it past the first checkpoint in Chicago.

He was wrong. The Flyer and its intrepid team survived unimaginable hardships to eventually reach the West Coast in a record-setting 42 days. The next leg would eventually take them across the Pacific Ocean to Japan (the planned crossing of the frozen Bering Straits that temporarily connects Alaska and Russia was abandoned). After another short sea crossing to Vladivostok, Russia, from Japan, the teams set off on the Asian and European portion of the event.

Crossing the Siberian tundra proved to be the toughest endurance test for the men and the machines. Breakdowns were frequent and much of the ground consisted of thick, muddy bog that often required hiring teams of horses to keep the cars moving. Where no roads existed, the vehicles were driven along railway right-of-ways, which proved somewhat uncomfortable since the tires would bump and thump over the wooden ties for up to hundreds of miles.

After battling their way across Siberia and Russia, the teams finally found easier road and weather conditions as they made their way into Germany and France.

On the 169th day after leaving New York -- July 30 -- Schuster and the Flyer rolled across the finish line in Paris with an unfurled American flag proudly trailing in their wake. They had traveled a total of 22,000 miles, of which about 13,500 miles were on land.

The second-place German Protos team arrived in Paris 26 days later, while the Italians in their Zust finally completed the final leg on Sept. 17. None of the three French entries completed the race.

By that time, Schuster's group had triumphantly returned to America, been feted with a ticker-tape parade through New York City and had recounted their adventures with a thoroughly enthralled President Teddy Roosevelt.

Today, the authentically restored Thomas Flyer reposes in climate-controlled comfort at the National Automobile Museum in Reno, a far cry from the inhospitable conditions that its determined team endured more a century ago.

Malcolm Gunn is a feature writer with Wheelbase Communications. He can be reached on the Web at www.wheelbase.ws/mailbag.html Wheelbase supplies automotive news and features to newspapers and Web sites across North America.