Despite economic boon, tiny town of Gerlach divided over Burning Man festival

GERLACH

Along a narrow two-lane highway, a week before the counterculture colossus known as Burning Man would ignite for another year, the faithful were already arriving — howling out of car windows at the midday sun, getting stoked for that Mother of all Parties in the desert.

The motley procession rolled into this former gypsum-mining town of 120 residents located 90 minutes northeast of Reno — beat-up clunkers without air-conditioning (the occupants often bearded, camouflage-clad, tattooed and sweaty), campers with zen murals and bumper stickers proclaiming “Stay Calm and Burn On,” “Beverly Hillbillies”-type trucks pulling ramshackle trailers overloaded with party paraphernalia and the heavy machinery needed to construct a temporary city in the nearby Black Rock Desert.

The reception was decidedly bittersweet.

Along the town’s tiny main drag, a few residents set up “last chance” booths to sell suntan lotion, goggles and bandannas to protect against the incessant dust that blows across the playa, the festival site’s ancient lake bed, located just a dozen miles away.

Others draw a line in the sand — like the man who blocked off his driveway, shouting at strangers and scowling at the RV occupants who stopped to stretch their legs.

Another developed a foolproof method to discourage outsiders seeking RV space: “I quote them the long-term parking rates at JFK airport; that steers them away.”

BURNISHED FORTUNES

Burning Man is no run-of-the-mill festival. A combination of Grateful Dead concert and NASCAR rally, the alternative desert party billed as a gathering of artistic self-expression has been thrown here since 1990. Known for its outrageous participatory art, New Age ethos and bohemian free-spirit drug culture, capped off with the torching of the symbolic burning man at the 5-square-mile site named Black Rock City.

As always clothing will be optional for this year’s estimated 70,000 participants, who paid $400 per ticket and reportedly will bring a significant $50 million boost to the Northern Nevada economy.

Yet Gerlach remains a town divided over the annual Burner invasion: Many insist the weeklong festival, which kicks off today, provides necessary, if temporary, jobs for an area that has lost both its gypsum mine and drywall plant. Festival-related workers who now live here full time, adherents say, will invigorate Gerlach with young families and a fresh way of looking at life.

MIXED FEELINGS

Still, not everyone here is a Burning Man believer. Critics complain of traffic jams from a nonstop party that does little for the town itself. Officials started selling water after Burners were caught siphoning water from neighborhood hoses. They closed the town park to discourage outsiders without festival tickets who linger around town with no money to eat or rent rooms.

And they gripe that property purchases by festival planners — including a trailer park and local hot springs — will change Gerlach from a simple blue-collar town to a pretentious hipster-central community, bringing with it an entitled San Francisco-type vibe.

“Burning Man is a Medusa that each year grows more heads,” said John Bogard, who owns a pottery business here. “And don’t think of chopping any of them off, because their lawyers are better than your lawyers.”

Washoe County Sheriff Chuck Allen said a retired couple recently called to complain that the traffic and noise was ruining the town. “I told them if they didn’t like all that hubbub, they should take an extended vacation during festival week,” Allen said. “I think they ended up selling.”

Will Roger, a Burning Man founding board member, maintains Gerlach should welcome the change. “We’re bringing a sense of community and freedom of expression you don’t find in other places,” said Roger, who owns a house here. “Gerlach is going to become an arts community.”

‘THESE PEOPLE ARE THE FUTURE’

On a recent day, a steady stream of Burners filed into the Bruno’s restaurant and bar, the town’s mainstay business, stocking up on beer and waiting to reunite with fellow partygoers they see only at the festival. There were women in dreadlocks and men with red mohawks, one bearing a bone in his nose, paying $9 for a 12-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon to go, sharing space with mostly blue-collar locals with trucker caps and sunburned faces.

Waitress Lacey Holle rushed to fill orders with a welcoming smile. “This is the dawn of a new era for Gerlach,” she said. “The mining culture is dead; the old miners are dying off. These people are the future.”

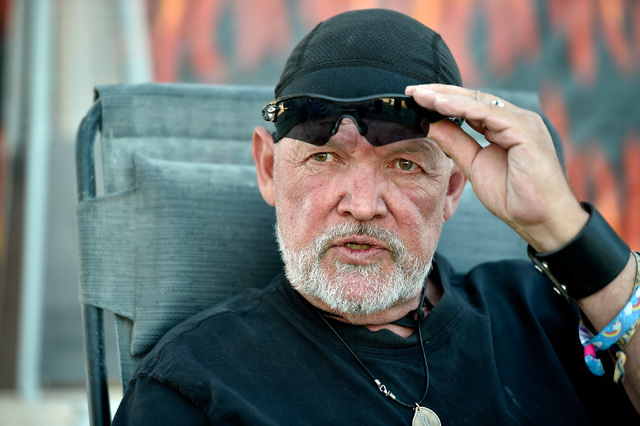

Sitting nearby, Steve Miller — a local resident who also attends the festival every year — sees Burning Man from both sides. A burly man with a thick white beard, he moved here 17 years ago to take a job at a nearby geothermal power plant and has attended Burning Man ever since. He offered a litany of complaints, saying festival planners have offered little of its much-heralded art for the town and failed to take steps, including using local rail to ship in equipment, to cut down on traffic and accidents along the lone highway into town.

“They’ve had 20-odd years to make a difference here and what have they done?” he asked.

Miller worried that festival operators’s recent purchase of the local Fly Geyser would turn the natural wonder into an exclusive haunt for celebrities and high-tech notables such as Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who regularly attend Burning Man.

He winces at the entitlement exuded by the festival crowd, who, he said, believe they alone are keeping Gerlach alive.

“They come in here looking for gluten-free everything. Hey, look around, this is the central Nevada desert!” Miller said. “But most annoying is that attitude that says, ‘Look what we do.’ Well, screw you. Gerlach was here long before you arrived and will still be here when you leave.”

Down the street at the Burning Man office, set up in a former general store, worker Cameron Hall has also made her mark here; she lives here full time and is now engaged to Jon Farnsworth, who works for the local water board.

“It does kind of feel like we’re taking over,” she said. She gets complaints from people who say the festival has ruined the lake bed for wind sailors, overshadowed the town’s folksy Labor Day pottery festival and angered big game hunters who converge here in early September.

”I know people would prefer we not be here, but look at it this way: LA is a different place than what my parents found in the 1960s,” she said. “What do you say to them? Things change.”

She sighed. “I don’t know. I’m just pretty mellow about the whole thing.”

EMBRACING THE CHANGE

Michael “Flash” Hopkins, a onetime Gerlach chamber of commerce president who rents campers to Burners, likens the change to a Northern California logging town moving toward a marijuana-growing economy.

Hopkins said he was involved 25 years ago in breaking the Burning Man idea to locals who “didn’t want those hippies ruining their town.” “They called me all sorts of names, but I warned them, ‘They’re coming over that hill. Get ready for it.’ The reality here is many people don’t want any kind of change at all, and that’s just not reality.”

Later, as dusk set in on the festival site, Roger sat on a lounge chair at his base camp on the playa; dressed in black, smoking a Cuban cigar, he surveyed his rising city like a smug Bedouin chieftain. Waving off critics, he said his board was working on all kinds of ways to make Gerlach a better place — to bring new art and jobs, and lessen stress on residents.

He insisted that most residents embraced his festival, which he said was good for the town, its economy and the environment. As he walked out onto the lake bed soon to be overrun by a tribe of countless Burners, he stopped to pick up a cigarette butt.

“See what I just did? he asked. “I picked that thing up, and all of us are trained to do that, to each leave this place just as we found it.”