Program helps disabled and their caregivers reach potential

When Diana Rovetti’s son was born with Down syndrome in 1998, she was overwhelmed because she didn’t know how it would affect her life.

“I was depressed,” she recalls. “I felt sorry for him. I felt sorry for myself.”

That was until she found Partners in Policymaking that same year, a program that gives those with developmental disabilities and their caregivers resources and tools to have a more productive life and teaches them to become better advocates for issues affecting them.

“The class changed how I viewed my son and others like him,” she says. “There is nothing wrong with people with disabilities. They just do things differently.”

Partners in Policymaking was created in the mid-’80s by Dr. Colleen Wieck in Minnesota. She was the executive director of the Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities when she saw the need for a program that would cater specifically to people with disabilities or with developmentally disabled children.

The program slowly expanded to other states, coming to Nevada in 1998.

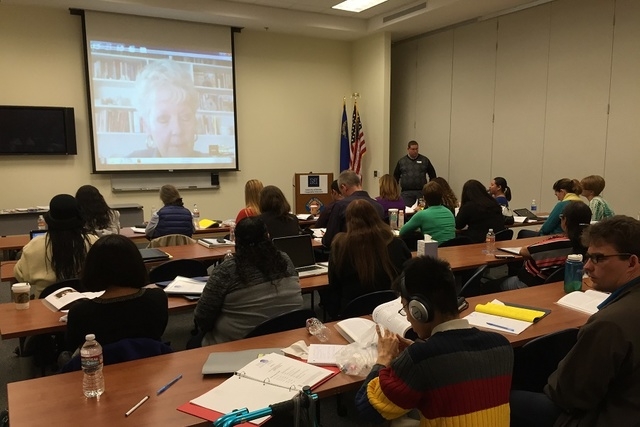

Partners in Policymaking, which is housed at the Nevada Center for Excellence in Disabilities at the University of Nevada, Reno, meets in eight-hour sessions once a month over eight months. The program switches back and forth between Reno and Las Vegas.

“We probably cram two days’ worth of material into one eight-hour day,” Rovetti says.

The course touches on the history of treatment of disabled people, how to enrich the home and work life, what tools are needed along the way and tips on how to get involved in community organizing.

“It starts very simply with how to advocate for yourself,” Rovetti says. “Then it teaches how to influence on every level. You’re not just doing it for yourself. It teaches you how to create a system of change.”

Rovetti participated in the first session offered in Nevada. She learned the bleak history of attitudes toward the disabled, which usually included institutionalizing them or segregating them in school.

“When I grew up, they were all in a separate class,” she says. “I was always afraid of them because I didn’t know any better. I didn’t have any interaction with them.”

Also in the late 1990s, Rovetti was a part of another group program called Early Intervention, which helped parents who had children with disabilities. When she heard a new program was being set up, she decided to try it.

“I wanted to do anything that would give my son the best shot of life,” she says.

The experience changed Rovetti’s outlook and her son’s life. For instance, she made sure her son was included in regular classes.

“I think this program really paid off,” she says. “I think I would have had a very different outcome without the program.”

Her son Jack, 16, runs a popcorn cart in Reno. Rovetti says the family opened the popcorn cart in 2014 and started attending events in Reno to promote the project.

“It’s a franchise so it made it easier to set up,” she says. “He has set up at the art festival up in Reno and a few other events. He plans to be at the Earth Day event in April.”

After he graduates from high school, she wants to help him get a permanent location.

“Maybe like a kiosk in the mall,” she says.

Her biggest lesson was learning to give her son, and other developmentally disabled people, a chance to succeed.

“They don’t reach their full potential if they are not given a chance,” Rovetti says.

Kathie Snow, who took a Partners in Policymaking class in 2001, is now a presenter at the class.

“I went from a stay-at-home mom to a public speaker,” she says. “That’s what happens when you get passionate about something. The class was life-changing.”

Her son just graduated with his master’s degree, something she doesn’t think would have been possible if she hadn’t connected with Partners in Policymaking when he was young.

The program is not just for family members. Developmentally disabled adults can take the courses, too.

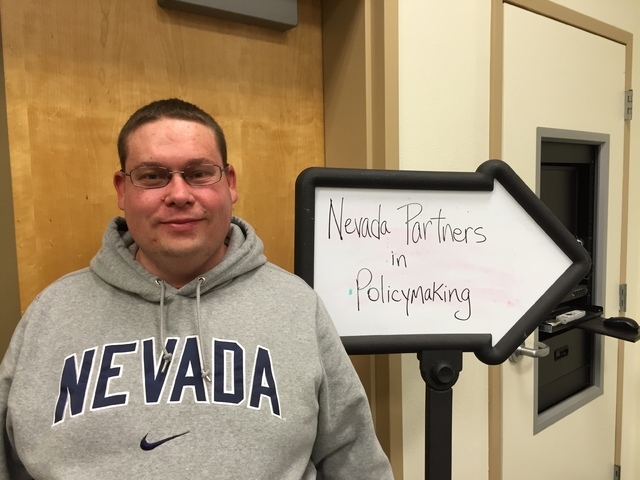

Travis Mills was born with a learning disability and never thought the life he lives now would be possible before he went through the program.

“They helped educate me to be a better advocate for myself,” he says.

He signed up for the same class in 1998 as Rovetti. Since taking the class, Mills has been able to get a better job working at UNR and even has his own house.

The class not only improved Mills and Rovetti’s family lives, it gave them a new sense of purpose.

Since the class, Rovetti has worked for several organizations that help people with developmental disabilities. She started this work in 2001, involving herself with the Outcomes Project at UNR.

The project conducted interviews with developmentally disabled adults to survey their quality of life in Nevada.

“We would report our findings to the Legislature,” she says. “We lost funding in 2007 because of the recession. The state was cutting back services.”

Rovetti was then recommended for a project director position for Partners in Policymaking.

“I knew the program was important and someone needed to run it,” she says. “So I took the job.”

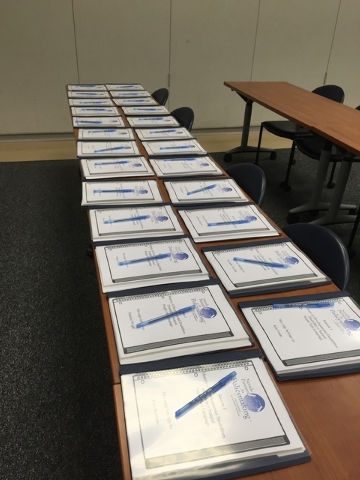

Mills also is employed at the Nevada Center for Excellence in Disabilities at UNR as a co-trainer with Partners in Policymaking. He organizes the packets and binders used in all the classes, emails reminders to participants and helps lead meetings.

Part of the training includes how to get involved with lawmaking on a local, state and federal level.

Some strides have been made to ensure the rights of the disabled — 2015 is the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, which prohibited discrimination against those with disabilities. But observers say there are still steps that need taking.

Snow says it is important to have policymakers hear directly from people affected by disabilities.

“Many times, they don’t view them as voters, so they get left out,” Snow says.

Mills, along with family members like Rovetti, has advocated for many bills in Nevada to ensure that the rights of intellectually disabled people are protected.

Many from the group are rallying behind Assembly Bill 128, which updates language on the right of attorney.

Rovetti says in many cases, that right is taken away from people with developmental disabilities. The new bill would create a power of attorney for health care decisions for disabled adults.

The bill has been heard only in the judiciary committee.

Although families know the program’s benefits firsthand, that knowledge doesn’t often translate into getting it fully funded.

Funding issues have kept the program from being offered every year.

“It’s a shame,” Rovetti says. “This should be offered every year.”

Partners in Policymaking runs on about $55,000, which is funded through the state.

Because of a bare-bones budget, the class can accommodate only 25 participants. There’s always a waiting list, Rovetti says. One woman who emailed may have to wait two years until the program is back in Las Vegas to attend.

“We need to have this every single year,” Rovetti says. “Every year, kids are diagnosed with a disability. This program gives parents the tools to help them advocate for their kids.”

Contact reporter Michael Lyle at mlyle@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5201. Follow @mjlyle on Twitter.