Treatment of Muslim-Americans is compared to WWII Japanese internment

It was nearly three-quarters of a century ago, but Rosie Maruki Kakuuchi clearly remembers the fear that stemmed from the simple fact that she was a Japanese-American.

"You don't know how scary it was when you're listening to the radio and there's all this blasting about Japs," said Kakuuchi, now 90 and a resident of Las Vegas. "Our parents were scared, too, because they didn't know what was going to happen."

Anti-Japanese sentiment, which had been festering for decades, came to a head with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in late 1941. Every Japanese-American — even those who were born in this country — suddenly was under suspicion.

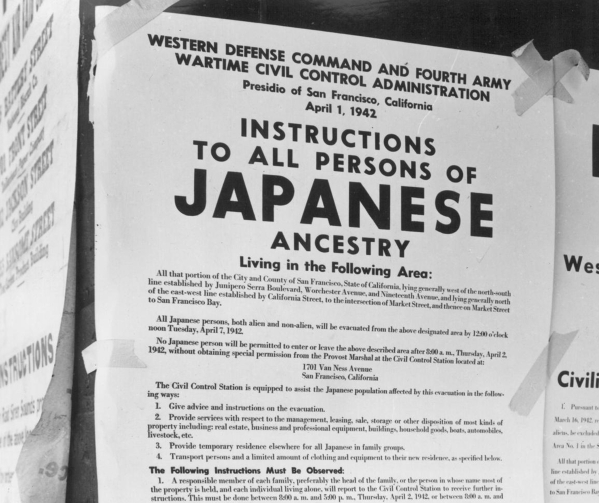

The U.S. government's plan became clear in February 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the removal of anyone who might pose a threat to the war effort. Everyone of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast — 120,000 men, women and children — was ordered to travel to 10 relocation centers in seven states, in many cases with not more than a week's notice, taking only what they could carry. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens. Most of them would remain in the camps for more than three years, surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

Kakuuchi, like other former internees, wants to ensure it doesn't happen again, but the possibility seems real.

During a Wednesday visit to the Islamic Society of Baltimore, President Barack Obama condemned "inexcusable political rhetoric against Muslim Americans that has no place in our country."

"Like all Americans, you're worried about the threat of terrorism, but on top of that, as Muslim-Americans, you also have another concern, and that is your entire community so often is targeted or blamed for the violent acts of the very few," Obama said.

In November, Yahoo News asked Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump whether his ideas for increasing surveillance of American Muslims could include such things as warrantless searches, identity cards or some sort of physical identification. He didn't rule any of it out.

"We're going to have to do things that we never did before," the website quoted Trump. "And some people are going to be upset about it, but I think that now everybody is feeling that security is going to rule. And certain things will be done that we never thought would happen in this country in terms of information and learning about the enemy. And so we're going to have to do certain things that were frankly unthinkable a year ago."

In December, Trump told Time that he didn't know whether he would have supported or opposed the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

"I certainly hate the concept of it," he said. "But I would have had to be there at the time to give you a proper answer."

Last year, retired general and past Democratic presidential candidate Wesley Clark told MSNBC the federal government should use internment camps for "disloyal Americans" who become Islamic extremists. "If these people are radicalized and they don't support the United States and they are disloyal to the United States as a matter of principle, fine. It's their right and it's our right and obligation to segregate them from the normal community for the duration of the conflict."

Such talk is horrifying to those who lived through internment.

"I think it would be horrible to do that to another group of people," Kakuuchi said. "The Japanese people, they lost everything. Our parents worked all their lives, and then in one week's time they lost everything."

Aslam Abdullah, director of the Islamic Learning Center in Las Vegas, agrees.

"I think the possibility of someone saying these kinds of things always exists," Abdullah said. "The probability of someone doing that also exists. But I think it's very difficult to have such kind of a thing happening in this country because of the consciousness and the commitment of the people to certain ideals. They would never allow fellow human beings to suffer the way the Japanese suffered, or the way the Jews suffered in the second World War."

POST-9/11 BACKLASH

John Tateishi, now 76 and a resident of the San Francisco Bay Area, was just 3 when the government came for his parents and their four children, all of whom had been born in the United States. The young Tateishi was diagnosed with German measles on the day the family was to depart, so he was held back.

Tateishi would eventually go on to become national redress director for the Japanese American Citizens League. Beginning in the late '70s, the league worked for reparations, which bore fruit in 1980 when Congress passed a bill to create a commission to address the matter. The commission's report to Congress in 1982 blamed the internments on "racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a failure of political leadership." President Ronald Reagan referred to the internments as a "grave injustice," and the survivors got a presidential apology and $20,000 for each surviving internee. The money, Tateishi said, was slim recompense for three years of their lives and the loss of possessions, businesses and careers. And at any rate, he said, the goal was more forward-thinking.

"We did this campaign so this would never happen in the future," Tateishi said. "To prevent this madness from recurring in the case that, God forbid, there would ever be something happening in the United States to cause a backlash against any one community."

That backlash would start with 9/11 in 2001. Tateishi clearly remembers Peter Jennings reporting on the attacks that day on New York and Washington, D.C., and the attempt on the White House that ended in a Pennsylvania field.

"I knew that any Muslim-American or anyone who looked like them would be vulnerable," he said. "There are apparently enough people in this country who hate anyone who doesn't look like them."

Michael Kagan, a professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and co-director of the school's immigration clinic, has visited Manzanar — which now is a National Historic Site — and lived in the Middle East for 10 years.

"Having been to a Muslim country, the fear Americans have of all Muslims strikes me as bizarre," Kagan said. "We have white Americans who engage in mass shootings, but we don't fear all white Americans. But I think when we see mass violence by Muslims, people apply that impression to all Muslims."

"After they arrested Timothy McVeigh, I didn't see them rounding up a bunch of white men," Tateishi said.

The anti-Muslim rhetoric seemed to die down for a while. And then came the attacks on Paris in November and on San Bernardino, Calif., in December.

Some of the presidential candidates, Tateishi said, "are playing to a fear of something that doesn't exist. It was shocking to hear someone like Trump, with all the trash and nonsense about Syrian refugees. What was more shocking was his following."

LIFE IN AN INTERNMENT CAMP

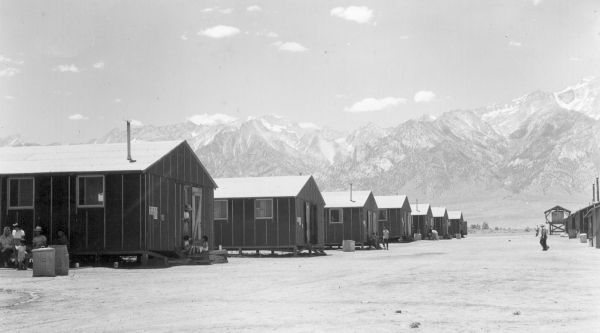

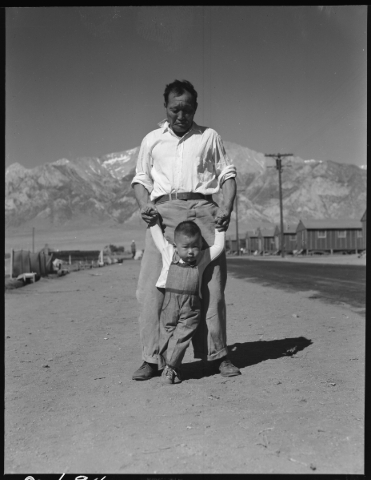

It's safe to say Tateishi isn't someone who's shocked easily. Once he had recovered, three weeks after his family left, the toddler was taken by train to Manzanar, which is in the remote eastern Sierra about 3½ hours from Los Angeles, 4½ hours from Las Vegas. Comparatively speaking, the Tateishi family was among the lucky ones; some families were sent as far as Arkansas or Wyoming, with a stop in a temporary assembly center along the way.

But that "comparatively" is a big qualifier. The camps tended to be in either swamps or deserts. In the case of Manzanar, it was the latter. And conditions there weren't exactly what the internees were used to. Like many of the others, Kakuuchi's family was sent to the wind-swept camp from their home in downtown Los Angeles.

"It was a rickety train — the kind you see in Western movies — and the bench seats were hard," said Kakuuchi, who was 16 at the time. "The sentry guards came in and pulled down all the shades, so we couldn't see where we were going. Finally, when we got to Lone Pine, they told us to get out — the sentries with their guns, to make sure nobody got out of line. We had no idea where we were going, just saw dusty, wind-blown Japanese people standing around looking to see if any of their friends arrived."

At the camp, they were marched out of the bus in single file and each issued two blankets, a peacoat and a straw mattress. Their new home would be block 21, barracks H, apartment 3. The "apartment" was a 20-by-25-foot room shared by Kakuuchi, her parents, one sister and her brother. For a time their space also was shared by three strangers, two adults and a child.

"It was just a floor with planks that had spaces, and when the wind blew, the dust just came up," Kakuuchi said.

Grace Nakano Seto, 80, now a resident of Los Angeles, may have been only 6 years old when her family was sent to Manzanar, but she, too, remembers the dust. Both also remember the lack of privacy.

"I just hated the communal toilets and the communal shower," Seto said. "Within the latrines, there were five or six back to back. And in the beginning there were no partitions. As young as I was, I just hated that. I'll never, never forget that. To this day, I remember I always tried to find the toilet that was in the back, in the corner, so nobody could see me."

Tateishi remembers being warned away from the border fence.

"Here's a soldier up in a guard tower with a gun pointed at us," he said. "I was terrified. My sense of where we were was really constructed around this perimeter. I would tell my brothers, 'I want to go to America. I want to see what it's like.' "

Some young men of Manzanar did leave — to go to war, where some of them would die, their Gold Star Mothers still locked up in the camp.

Most of the internees tried to make the best of it, in line with the Japanese principle of "shikataganai," which means, loosely, "it cannot be helped." Seto and Kakuuchi said they were fortunate that the elders in their families worked to keep their large family groups together.

The internees were paid $12 to $19 a month, depending on their skills. They worked together to establish the Manzanar Free Press and had a general store, beauty and barber shops and a bank. Kakuuchi remembers her mother making curtains for their apartment and her father crafting rudimentary furniture. Many of the internees were gardeners, and the remnants of their traditional gardens remain today. Kakuuchi graduated from high school there.

Health care was not the best, though; her sister died in childbirth, followed shortly by her twin babies. Kakuuchi is particularly saddened that her sister died during the first year they were there, without learning if they would ever be released.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The Manzanar National Historic Site, which is operated by the National Park Service, has extensive displays that recount the history of the relocation centers. And the anti-Japanese racism is evident in the photos of hate-filled slogans posted even before Pearl Harbor.

"Race and race alone was the factor that put us into these concentration camps," Tateishi said. "Pearl Harbor was the rationale for what politicians and the public had been trying to accomplish for 50 years."

Seto sees a familiar pattern in rage against Muslims.

"It's going to be the same repeat situation that was done to us," she said. "And I think to some extent, the public is getting a little hysterical about this, without thoroughly thinking through what's happening. No, I'm not for it at all."

Kakuuchi hopes we're a little more enlightened now than we were then.

"The Muslims are very lucky that the media and the leadership are supporting them, and they're telling us not to hurt them because of their religion," she said.

But as to whether a mass internment of one group could happen again, Kagan had his doubts.

"Legally, I think there are signs of progress," he said, "in that the Supreme Court decision that upheld the internment of the Japanese has been largely disavowed.

"There is a very big difference than in the 1940s, when the government told the court, 'We think all Japanese and Japanese-Americans are a threat.' Whereas today, so far — through both the Bush administration and the Obama administration — the government has said, 'We do not think all Muslims are a threat.' "

Abdullah said there's another difference now, compared to the World War II era.

"We have learned enough lessons," Abdullah said. "The generation that's in the leadership now does not believe in those ideas, although some politicians might use those ideas as part of a vote-grabbing strategy."

"When it was our turn," Kakuuchi said, "there was no support."

— Read more from Heidi Knapp Rinella at reviewjournal.com. Contact her at hrinella@reviewjournal.com and follow @HKRinella on Twitter.