Case revealed law’s faults

"A person who engages in a good faith communication in furtherance of the right to petition is immune from civil liability for claims based upon the communication."

-- NRS 41.650

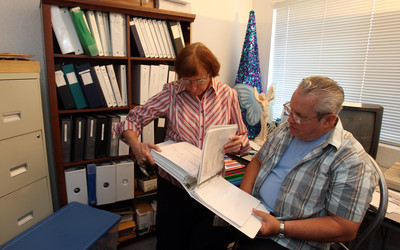

Nevada 10 years ago adopted an anti-SLAPP law intended to discourage real estate developers and other wealthy interests from filing malicious lawsuits aimed at shutting up vocal critics. But those regulations did not protect Frank and Audrey Lockwood when they were sued by a medical company they blame for their daughter's death.

The Lockwood case calls into question the law's effectiveness. It's hard to evaluate because Clark County district courts have sealed at least 115 civil lawsuits, including the one against the Lockwoods, since the law was passed; how many of the others are about silencing criticism is hidden from public view.

The Lockwoods' daughter stopped breathing at a Nevada Imaging facility in January 2004 and was taken to a hospital, but doctors could do little before she was transferred to a hospice and died.

Nevada Imaging sued the Las Vegas couple and alleged libel after the Lockwoods mailed to similar companies packets with information on their daughter's death and inquiries about policies and procedures at such facilities. The family has said it was gathering information for a wrongful-death lawsuit, but the company said the family set out to destroy its reputation.

The company added an allegation of slander to its lawsuit after Frank Lockwood, during a visit to the facility after his daughter's death, turned to his wife, pointed to the recovery room and said, "That's where they murdered our daughter."

Additional details of the case are unavailable because all records in the case were sealed by Clark County District Court Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez the same day the lawsuit was filed in May 2005.

A lawsuit aimed at silencing critics on matters of public interest is known as a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. Nevada is one of 24 states that have anti-SLAPP laws providing differing degrees of protection against the malicious court actions, experts said.

Kevin Diamond, an attorney for the Lockwoods, who declined to comment in detail about the case because it had been sealed, said that Nevada's anti-SLAPP law did not apply to the Lockwood case but that it might have been dismissed under California's more comprehensive anti-SLAPP law.

Nevada Imaging's case was like a textbook SLAPP: The defendant was accused of defamation or libel; the defendants' public criticism stopped when faced with the threat of a lawsuit; the case dragged on for two years without a trial; and the lawsuit was dismissed after the plaintiff failed to substantiate the allegations.

Mark Goldowitz, director of the California Anti-SLAPP Project, agreed the Nevada Imaging lawsuit showed the earmarks of a SLAPP case. Nevada's law should be strengthened if it is to truly protect free speech, he added.

One flaw with Nevada's decade-old law, he said, is a clause that says the defendant can't knowingly make false statements about the plaintiff.

Goldowitz said that permits the plaintiff to call for pretrial discovery and hearings to determine whether the defendant made false statements "knowingly." Meanwhile, a defendant has been silenced and is faced with mounting legal costs as the case drags on.

Laws in other states call for judges to dismiss SLAPP cases quickly before such a discovery process ensues, Goldowitz said.

"You want to protect the free flow of information ... and the way to do that is to make such petitioning activity absolutely privileged rather than dependent on the defendant showing good faith, which leads to the fact quagmire," Goldowitz said. "The whole purpose of strong anti-SLAPP legislation is to avoid the fact quagmire."

Sean McCallister, director of the SLAPP Resource Center in Denver, said Nevada's law seems flawed in another way. The free speech it seems to protect is limited to communication between the public and a government agency. About nine states, including California and Massachusetts, have stronger anti-SLAPP laws that protect any comment made on an issue of public concern, he said.

"I would characterize it (Nevada's anti-SLAPP law) as bottom of the barrel or something that provides the minimum protection from a SLAPP suit," McCallister said.

But McCallister acknowledged one strength in Nevada's law: Courts can issue punitive damages against a plaintiff who files a SLAPP. Some anti-SLAPP laws provide no such penalties.

Former Assemblywoman Genie Ohrenschall, D-Las Vegas, author of the 1997 anti-SLAPP law, defended the legislation. It appears to be working, she said, because a spate of SLAPP cases brought by developers in the mid-1990s dried up after the law was enacted, she said.

Ohrenschall is one of 372 commissioners with the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, which recommends to Congress state laws for federal consideration. She said she plans to propose Nevada's anti-SLAPP law as a model for the nation.

"The amount of nonuse of the SLAPP suits is significant because it shows it's not being used to shut other people up," she said. "You are not seeing this happening much any more, which means the law is having its deterrent effect."

Ohrenschall acknowledged that the "good faith" provision might give plaintiffs an edge. According to the legislative record, she opposed the provision in 1997 but was unsuccessful in removing the amendment from her bill.

Even so, she said last month, judges have the authority to shorten any delays posed by the discovery process or to dismiss a malicious lawsuit at any time.

"The judge has the power to limit how far the discovery can go and how long it can go on," she said. "The judge has the authority to cut short discovery if he thinks the discovery is a waste of time."

District Judge David Wall didn't see it that way in 2003 when he ruled on a case characterized as a SLAPP.

The lawsuit was brought by developer D.R. Horton against a group of homeowners whose Web site criticized the company and alleged construction defects. In his ruling, the judge said that the anti-SLAPP legislation tied his hands and that he could not dismiss the case.

Wall's ruling noted the homeowners' argument, which said that the discovery process is "antagonistic" to the law's intent of preventing a SLAPP from "exhausting the financial capacity of the person or organization exercising their constitutional right to free speech" by prolonging the case.

The ruling concluded, "Notwithstanding those concerns, (the state law) was enacted with language limiting protected communications to those made without knowledge of their falsehood. In effect, the statute as enacted may thwart a portion of its intended purpose by providing a safe harbor for plaintiffs, who need only allege and support by affidavit a contention that comments were made with knowledge of their falsehood."

Contact reporter Frank Geary at fgeary @reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0277.

Sealing the Case

NEVADA'S ANTI-SLAPP STATUTE NRS 41.637 "Good faith communication in furtherance of the right to petition" defined. "Good faith communication in furtherance of the right to petition" means any: 1. Communication that is aimed at procuring any governmental or electoral action, result or outcome; 2. Communication of information or a complaint to a Legislator, officer or employee of the Federal Government, this state or a political subdivision of this state, regarding a matter reasonably of concern to the respective governmental entity; or 3. Written or oral statement made in direct connection with an issue under consideration by a legislative, executive or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law, which is truthful or is made without knowledge of its falsehood. (Added to NRS by 1997, 1364; A 1997, 2593) NRS 41.640 "Political subdivision" defined. "Political subdivision" has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 41.0305. (Added to NRS by 1993, 2848; A 1997, 1365, 2593)v NRS 41.650 Limitation of liability. A person who engages in a good faith communication in furtherance of the right to petition is immune from civil liability for claims based upon the communication. (Added to NRS by 1993, 2848; A 1997, 1365, 2593) NRS 41.660 Attorney General or chief legal officer of political subdivision may defend or provide support to person sued for engaging in right to petition; special counsel; filing special motion to dismiss; stay of discovery; adjudication upon merits. 1. If an action is brought against a person based upon a good faith communication in furtherance of the right to petition: (a) The person against whom the action is brought may file a special motion to dismiss; and (b) The Attorney General or the chief legal officer or attorney of a political subdivision of this State may defend or otherwise support the person against whom the action is brought. If the Attorney General or the chief legal officer or attorney of a political subdivision has a conflict of interest in, or is otherwise disqualified from, defending or otherwise supporting the person, the Attorney General or the chief legal officer or attorney of a political subdivision may employ special counsel to defend or otherwise support the person. 2. A special motion to dismiss must be filed within 60 days after service of the complaint, which period may be extended by the court for good cause shown. 3. If a special motion to dismiss is filed pursuant to subsection 2, the court shall: (a) Treat the motion as a motion for summary judgment; (b) Stay discovery pending:v (1) A ruling by the court on the motion; and (2) The disposition of any appeal from the ruling on the motion; and (c) Rule on the motion within 30 days after the motion is filed. 4. If the court dismisses the action pursuant to a special motion to dismiss filed pursuant to subsection 2, the dismissal operates as an adjudication upon the merits. (Added to NRS by 1993, 2848; A 1997, 1365, 2593) NRS 41.670 Award of reasonable costs and attorney's fees upon grant of special motion to dismiss; person sued for engaging in right to petition may bring separate action for damages. If the court grants a special motion to dismiss filed pursuant to NRS 41.660: 1. The court shall award reasonable costs and attorney's fees to the person against whom the action was brought, except that the court shall award reasonable costs and attorney's fees to this State or to the appropriate political subdivision of this State if the Attorney General, the chief legal officer or attorney of the political subdivision or special counsel provided the defense for the person pursuant to NRS 41.660. 2. The person against whom the action is brought may bring a separate action to recover: (a) Compensatory damages; (b) Punitive damages; and (c) Attorney's fees and costs of bringing the separate action. (Added to NRS by 1993, 2848; A 1997, 1366, 2593)