Victims say disease deadly, debilitating

Rebecca Kay remembers the September day four years ago: The trees in the Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City were swaying with the occasional wind gust.

She was attending a memorial service for her parents, who had died within a short time of each other.

Dust blowing from the soil meant to fill the grave -- her parents' ashes had been combined in one urn for the service -- sprinkled the mourners with specks of grit.

As she tossed a handful of dirt into the grave, a rush of air blew part of her offering back at her, causing her to cough and then clear her throat.

"I thought nothing of it," Kay, 63, said recently as she stood in the living room of her Henderson home with her husband, Doug. "I've always figured it is just part of living in the desert."

Three weeks later, after enduring a week of racking coughs, an excruciating headache that wouldn't go away, and joint pain and fever, Kay recalls "dragging herself" on a Sunday to the St. Rose Dominican Hospital de Lima Campus emergency room.

A doctor ordered a chest X-ray and left to work with other patients.

When the physician returned, he apologized to Kay and her husband for having to deliver the "bad news."

"I'm sorry to tell you that you have lung cancer," Kay remembers the doctor saying.

The spot on the lung looked bad, he said.

Doug Kay was incredulous.

"My wife had never smoked," he said. "I couldn't believe it."

Kay's primary care physician, who happened to be making rounds that day, didn't believe it either. She contacted infectious disease specialist Dr. Brian Lipman who ordered a blood test. Kay also had a painful lung biopsy.

Lipman told Kay she had Valley Fever, not lung cancer, and the Kays were so relieved.

But then they read about the disease, one that's rare in Southern Nevada but common throughout the Southwest -- particularly in Arizona.

The disease is contracted by inhaling fungal spores that become airborne after disturbance of soil contaminated by Coccidioides species. The organisms commonly reside in the ground of semi-arid areas.

The good news is that 60 percent of infections do not cause any symptoms. People who develop symptoms may experience fever, cough, headaches, rashes and muscle aches but make a full recovery within weeks.

"Often, people do not even go to the doctor for it," said Brian Labus, senior epidemiologist for the Southern Nevada Health District. "It just goes away on its own."

Others, like Kay, can suffer for months. And a small number of people develop chronic pulmonary infection or widespread infection.

When the infection spreads outside the lungs, it often affects the central nervous system and can result in meningitis, skin lesions and bone and joint infections.

The fungus is so potent that federal bioterrorism laws make it illegal for people to try and develop a delivery system for it.

Bob Miller, a 50-year-old Chicago resident, said he caught the disease in March while visiting his mother in Henderson. Miller said 7 feet of his intestine was taken out because doctors missed the Valley Fever diagnosis.

Doctors thought his vomiting, night sweats, headaches and loss of weight were manifestations of his Crohn's Disease, an inflammation of the intestine.

But during the July surgery, surgeons scraped out what they thought was cancer. It turned out to be tissue created by the Valley Fever fungal infection, which might have been treated successfully with anti-fungal drugs.

Miller said the tissue was sent to the Mayo Clinic, where the diagnosis was made.

Doctors determined he caught the disease in Henderson. He had run every day outside, he said. Chicago doesn't have the fungus.

"I had dealt 30 years with Crohn's Disease and didn't have to have surgery," he said. "And then this happened. I'm still too weak to go back to work."

KAY'S MISSION

Kay has been working to educate people about Valley Fever, which was given its name after a 1930 outbreak of coccidioidomycosis in California's San Joaquin Valley.

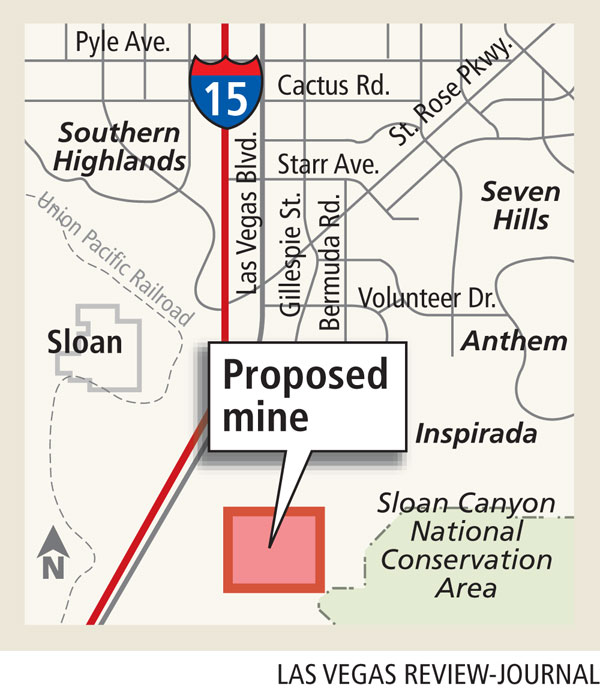

She is particularly concerned about a proposed open pit mine and rock crushing facility that would be built about 4 miles west of her Sun City Anthem home.

Kay argued in a letter to the Bureau of Land Management that the mine "would introduce much more particulate dust into the air," putting people at risk. The letter was forwarded to U.S. Rep. Dina Titus, D-Nev., who responded to Kay a month later.

The congresswoman said that she, too, had "concerns about the proposed CEMEX and Service Rock Products Corporation project."

"I find many aspects of the 640-acre project troublesome," Titus wrote, "especially its potential effects."

Over the past decade, Henderson residents have voiced opposition to construction of the mine, often arguing that dust created by the project could exacerbate existing respiratory problems.

But Kay's assertion that mining near a populated area could put people at risk of acquiring an incurable disease has not been part of the public debate as it has been in Arizona, where Valley Fever has hit epidemic proportions.

"In the 11 years that the Bureau of Land Management has been studying this site, not once has this rare health condition come up as a concern or reason to believe it could be," said Jennifer Borgen, a CEMEX spokeswoman.

In 2007, Arizona reported nearly 5,000 cases of Valley Fever to the CDC, and California 3,000. Nevada's 72 cases ranked a distant third, with fewer than 9,000 cases reported nationwide.

The CDC does not track deaths resulting from the disease, but in a 2007 attempt to appropriate funds for the Valley Fever Vaccine Project, Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., said between 200 and 500 people die annually from the infection.

Both Dr. Benjamin Park, an infectious disease specialist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Neil Ampel of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in Tucson, Ariz., say it is unclear why Arizona has so many more cases of Valley Fever than Southern Nevada when the environment is relatively similar.

The chemical balance of the soil in one area could be more hospitable to the fungus, they say. Arizona also gets more rain than Southern Nevada.

"This fungus that lives in the soil is highly affected by environmental and climate conditions," Park said. "There could be subtle changes in the soil. ... There's a lot of this that we just don't know."

Ampel said it is a mystery why the Las Vegas area isn't harder hit.

"For reasons we don't understand, the fungus is less (common) there. It just doesn't get into the air like it does in Arizona."

He said given all the construction in recent years -- activity that definitely disturbed the soil -- the Las Vegas area would be suffering an epidemic of Valley Fever if the soil was highly contaminated with the fungus.

"You obviously have patches of it. You have cases," he said. "But it's awfully messy to say that mining would definitely give you more when all the construction activity didn't produce it."

Park said no federal studies have found a correlation between mining activity and higher incidences of Valley Fever. He said logic would dictate there could be, however, given that spores are thrown into the air when contaminated soil is disturbed.

Park said it is known that fungal spores can be kicked up by natural events, including earthquakes and dust storms.

A study released by the Arizona Department of Health Services in 2008 found that some of the state's mining operations "are located in counties with the highest rates of valley fever."

But the study, undertaken "due to rising public concern," said while mining can produce large amounts of dust, "it is unknown if this actually increases the risk for valley fever."

The report stated: "It is known that the fungus grows only in the top layers of soil -- typically 2 to 8 inches below the surface. Sand and gravel mining operations work mainly at depths greater than two feet. Therefore, in theory, mining facilities should pose little risk for increased valley fever infection to those in the surrounding areas."

Borgen said scientific evidence should decide whether the mine can go into operation, not "misinformation to drive land use."

"Safety is a top priority of CEMEX," she said. "Should this project be approved by the federal government and CEMEX be awarded the right to mine after a competitive lease sale process, we will put in place all the safety, mitigation measures and mining requirements described by the Environmental Impact Statement."

The BLM is studying the environmental effects of the mine, with a final impact statement expected in mid-2010. Mining could begin that year.

OTHER EFFECTS

People of African-American, Asian or Filipino descent appear to be at increased risk for the infection, but scientists don't know why.

People with compromised immune systems are also at increased risk.

But you can also be in great shape, like Arizona Diamondbacks baseball player Conor Jackson, and still contract the disease. The left fielder has been on the disabled list since May, and still complains of extreme fatigue.

The disease may affect the brain and spinal cord, skin, bones and other organs.

Park said Valley Fever "is definitely something that should be taken seriously."

"There is a wide spectrum of illness involved with Valley Fever from those who don't know they have it ... to fatalities," he said.

In the past three years, 900 inmates at the Pleasant Valley state prison near Sacramento, Calif., have contracted the disease. Archaeologists digging for dinosaur fossils in Utah have gotten it. So have dogs sniffing for drugs on the Mexican border.

Doug Kay said when his wife contracted the disease her "immune system was way down because of having to deal with her parents' deaths."

Like most who experience serious symptoms of the disease, Rebecca Kay was given anti-fungal medication. Fluconazole is most commonly given. Side effects can include liver damage.

She became so weak that she often was bedridden. She had to quit her job as a massage therapist.

"I had a hard time breathing and thought I was going to die," she said.

It took almost a year before she "felt decent."

"But I really was lucky I was diagnosed as quickly as I was," Kay said.

At times, Park said, the disease mimics flu and pneumonia and isn't diagnosed by doctors for months.

"It just isn't on a lot of doctors' radar screens," he said. "It is undertested for and underdiagnosed."

That can translate to unnecessary treatment, including the kind of risky surgery that Miller endured in Chicago.

Animals also contract the infection. Las Vegas veterinarian David Henderson said as many as 2 percent of the dogs he treats for symptoms of extreme fatigue, vision loss, poor appetite, coughing, and bone pain show evidence of the disease following blood tests. Many of the dogs are put on anti-fungal medication for life, he said.

Sheila Danish, a former Las Vegan who now lives in Reno, said she figured out she had the disease after her two dogs were diagnosed with it.

Ever since her bout with the disease, Kay has conferred with Sharon Filip, a Washington state resident who caught Valley Fever in Arizona and nearly died.

Filip is co-author of the book, "Valley Fever Epidemic," which has been praised by CDC officials.

To illustrate the spread of the disease, Filip notes that the CDC reports as many as 50 percent of the people who live in a region where the disease is indigenous will have evidence of exposure to the fungal infection.

Filip raises money with book sales to foster research for a vaccine against Valley Fever.

But for now, health officials say there's little that can be done.

Regular masks won't keep the spores from being inhaled. It takes a special high-grade mask that archaeologists sometimes use to reduce the risk of contraction.

But the health district's Labus said that's just not practical in normal day-to-day life.

"Let's face it; we have to breathe," he said.

What helped fuel Kay's almost missionary zeal to inform people about the disease was the 2007 death of her son's friend, Doug Bradbury.

A diabetic who first got the disease in 2005 in Phoenix, Bradbury couldn't fight off the infection. No drug would help.

"The disease seems to shift into another gear when you have an underlying problem," Bradbury's brother, Steve, said in a phone call from his Oregon home. "It was a terrible death. It was almost like watching someone waste away from cancer."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.