Attorneys send a convention message: Knock off the knockoffs

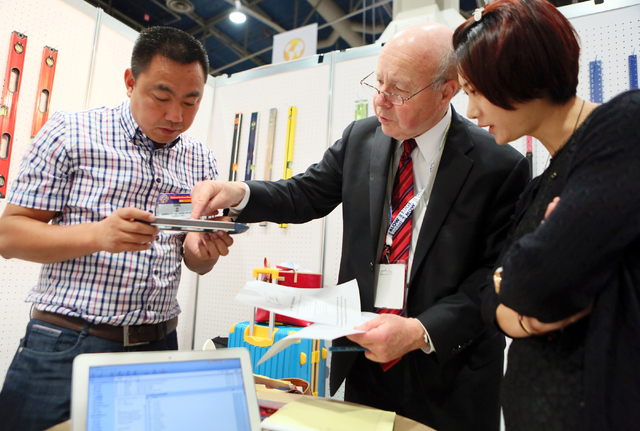

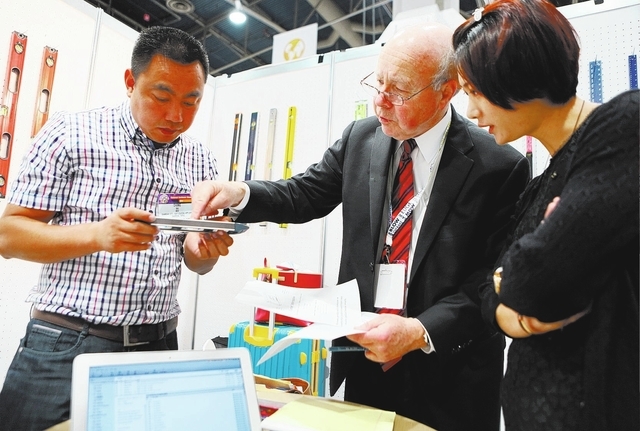

The men in suits stride with purpose as they march from booth to booth at the National Hardware Show at the Las Vegas Convention Center.

They are looking for one particular item at each booth — an Empire level, or at least something that looks like an Empire level.

The measuring tool is a durable, aluminum-cast torpedo level accurate to within 0.0005 of an inch.

This group isn’t your typical team of vendors and buyers that commonly attend trade shows. In fact, this group is doing more to put people out of business than to generate sales.

They are attorneys, and they are confiscating counterfeit goods that foreign companies are mass-producing abroad, showing at conventions and writing contracts to sell. They violate trademark law by producing products that look exactly like levels produced by Empire Levels, but they are cheap knockoffs.

Accompanying the attorneys are officers from the Clark County constable’s office to serve papers and maintain order if tempers flare. A representative of the management of the National Hardware Show also tagged along.

The group is led by F. Christopher Austin, a specialist in patents, trademarks and copyrights with Las Vegas-based Weide &Miller Ltd. law firm, and Peter Jansson of Jansson Munger McKinley &Shape Ltd., a Wisconsin firm specializing in a intellectual property law, and the lead attorney for Empire Level of Mukwonago, Wis.

THE GOAL: SURRENDER THE KNOCKOFFS

Their goal is to get eight Chinese companies to surrender their knockoff levels and serve their representatives with orders forbidding them from displaying or selling the fake products in the future.

They also are sending a message to others that Empire is serious about tracking down and punishing those who try to rip off their intellectual property.

“Not only do these counterfeiters hurt our business and our brand, they are a threat to our economy and American jobs,” said Jenni Becker, president of Empire Level.

“We refuse to sit still and allow the distinctive features of our products to be knocked off,” said Becker, the fifth-generation president of the family business, who spends some of her spare time teaching kickboxing to her employees. “It’s damaging to our company, and it’s not fair to the end customer who believes they’re getting a superior product when they’re not.”

The team ended up having a pretty good day at the hardware show. Eight notices were served to Chinese companies with names few people in the United States have heard of. When the team arrived at a booth to serve papers, most of the booth personnel were puzzled and had nothing to say. Some might have had limited command of the English language.

Still, Austin and Jansson were courteous throughout the process and did their best to explain what the companies they work for had done wrong. They emphasized that booth managers weren’t personally in any trouble but that it was important that they tell their bosses what had happened that day and to quit selling those levels because it was against U.S. patent laws.

For Austin, the experience at the hardware show was part of what he does regularly in his law practice.

He has worked at past National Hardware Shows for different clients and at the MAGIC Market Week fashion trade show, which notoriously is filled with knockoff clothing and accessories. Austin is one of a handful of Las Vegas attorneys equipped to pursue such cases. Most studied with respected intellectual property attorney Mark Tratos in Las Vegas.

With more than 20,000 conventions a year, Las Vegas is a perfect location for a trademark lawyer.

Sometimes, Austin is contacted by companies such as Empire Level to seek out counterfeiters. Other times, he will peruse a show floor with his camera in search of knockoffs. He will contact the companies that have had their goods duplicated and email pictures to see if they are interested in taking legal action.

MAKING AN OPEN-FIELD TACKLE

Austin has refined his process into an efficient timetable that has worked like clockwork for years.

Most trade shows are three or four days long. That gives Austin one or two days to walk a show floor in search of counterfeit goods. He has become so good at finding them that it usually takes less than an hour for him to make a list of questionable products.

Once he has been green-lighted to initiate a legal action — a process that will cost the contracted company $10,000 to $30,000, depending on the complexity of the case — he puts his team of paralegals, assistants and associates to work around the clock to produce the legal documents necessary to seek a temporary injunction from a judge. Austin’s team works through the night to have everything ready for a judge to review.

Austin generally pursues civil remedies, which have a lower burden of proof than criminal actions.

Once the order is signed by a judge, the fun begins.

Austin enjoys an adrenaline rush unlike any he gets in a courtroom when he’s in the field serving papers to potential trademark violators.

“That’s when we join up with law enforcement, and we run down there and serve the other side and seize the stuff,” he said. “That’s when it feels like you’re suddenly part of a SWAT team.”

That usually occurs on the last day of the trade show when companies are starting to pack up and leave. An end-of-the-show seizure presents the risk of missing a company that might have left early, but it’s usually appreciated by show managers who don’t want to see a confrontational disruption on the show floor.

Sometimes the action can get intense. Austin recalled an incident a few years ago in which he and a federal marshal confronted a vendor suspected of having counterfeit goods at a cafe at The Venetian.

“As we were serving him, he decided to bolt,” Austin said. “The instinctive reaction of the marshal who was with me at the time was to stop him.

“He tackled him and handed him the papers and said, ‘You’re served.’ That was the coolest.”

WINNING BY DEFAULT

In last month’s hardware show, the clockwork process nearly was disrupted because Austin couldn’t find a judge to sign the orders — most of them had gone to Reno for a judicial conference.

But Austin found a judge, got the orders signed and arrived at the convention center about 3½ hours before the show closed. Austin knew exactly where the booths of the alleged offenders were and drew a route map so that the team could move quickly from company to company to serve papers.

There were no unusual incidents when the papers were delivered, and in each of the eight cases 20 days later, Empire won by default judgment because representatives of the Chinese companies didn’t appear in court.

Austin said that’s what usually happens, but he always is prepared to argue a case.

The judgment serves as a red flag for future shows to be on the lookout for that company as a potential counterfeiter.

Sadly, Austin said, some Chinese companies view judgments as temporary setbacks and return with the same knockoffs under different names months later.

But a court judgment also helps Empire in its efforts to prevent counterfeit tools from entering the United States. The company is working with U.S. Customs, training agents about trademark infringement. Agents have been trained to seize any infringing goods.

If some goods make it through Customs’ scrutiny, Empire is armed with documentation to make legal claims and lawsuits against American companies that might have purchased the counterfeit goods.

Empire officials say that in most cases, U.S. sellers are quick to discontinue selling the knockoffs and pay damages and, in some cases, destroy the counterfeited merchandise.

Most American companies are eager to take up the fight against counterfeiters because the value of knockoff goods is expected to exceed $1.7 trillion globally by 2015 — 2 percent of the world’s total economic output, according to International Chamber of Commerce estimates.

Austin said companies should stay vigilant in their efforts to protect their trademarks because they will lose value if they are allowed to become a part of public domain. He cited the German pharmaceutical manufacturer Bayer, which once held the trademark to Bayer Aspirin.

Bayer didn’t aggressively protect the name, and aspirin eventually entered the public domain as a generic term for a pain reliever.

Contact reporter Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893. Follow him on Twitter @RickVelotta.