Data show high joblessness for Nevada teens

Unemployment remains high across Nevada, but the lack of work has fallen especially hard on the Silver State's teenagers.

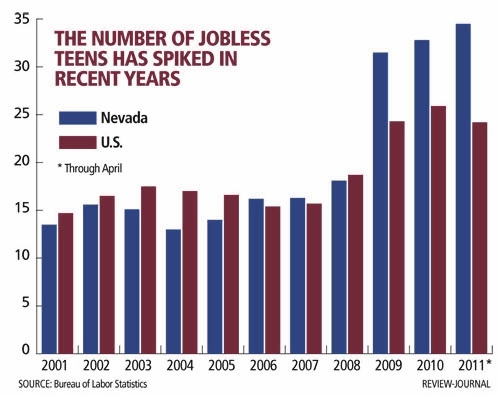

New numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that Nevada tied for second in the nation for teen unemployment in April, with 34.5 percent of people ages 16 to 19 looking for a job unable to find one. That compared with a national average of 24.2 percent. Include teens discouraged and no longer looking, and statewide joblessness in the age group rose to 36.2 percent in the month.

And Friday figures from the state Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation showed that Nevada employers hired 12,500 14- to 18-year-olds in the second quarter of 2010. That was down from 35,200 hires in the second quarter of 2006. Second-quarter data aren't yet available for 2011, but Bill Anderson, chief economist of the employment department, said it's likely teenagers will continue to have a hard time finding work.

"Given expectations for weak job growth on the whole this summer, competition for traditional summer jobs will be extremely tight," Anderson said.

That poor hiring climate is a problem because kids who miss out on working also miss out on developing lifelong soft job skills, such as learning to accept guidance gracefully, or to call in when they're sick instead of just not showing up.

"A job is more than a paycheck. Some people call it an invisible curriculum," said Michael Saltsman, a research fellow at the Employment Policies Institute, a nonprofit research group in Washington, D.C. "It's what you get from learning to report to a manager, working with customers and assuming the responsibilities that come with that first job. Teens who don't have that are taking a step back, and they'll be at a disadvantage relative to their peers who have experience."

Plus, research shows that those who don't work as teenagers make less money over a lifetime than do others because wages are based in part on experience, and less experience means smaller paychecks.

"An entry-level job is the first rung on the career ladder,'' Saltsman said. "Teens who have a spell of unemployment are at greater risk of earning a lower wage and seeing more unemployment later.''

Because early job experience is so important, experts say it's essential to address high teen unemployment. But finding solutions requires an understanding of why today's teens can't find work.

STIFF COMPETITION

For starters, the economy is still struggling, with unemployment at 9.1 percent nationally and 12.1 percent statewide. Throw in discouraged workers and underemployed part-timers who'd rather work full-time, and those rates jump to 15.7 percent and 23.7 percent, respectively. That means stiff competition from experienced or skilled adults willing to take hourly restaurant and retail jobs -- positions that go to high school and college students in better times.

"The reality is, unemployment is high for everybody, and more people are looking to fill roles that may have traditionally been filled by teens," said Amanda Richardson, senior vice president of product and marketing for SnagAJob, a Virginia-based job-search website that specializes in hourly positions. "It's definitely putting pressure on the teen job market."

Jeff Waddoups, a professor of economics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, also noted that teens tend to lack job skills, and unemployment is generally high for the unskilled. Numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that unemployment in 2010 was 14.9 percent nationwide for people with less than a high school diploma, and 10.3 percent for people with only a high school diploma. For the college educated, unemployment ranged from 1.9 percent for people with a doctorate to 5.4 percent for workers with a bachelor's degree.

"Firms like to keep skilled workers. They're more productive, and firms have spent a lot of time and money to develop skilled workers,'' Waddoups said. "When things slow down, they're hesitant to let their skilled workers go."

WHEN MINIMUM IS TOO MUCH

But rising labor costs share at least part of the blame for high teen unemployment, Saltsman said.

The nation's minimum wage has risen 41 percent since 2007, from $5.15 to $7.25. In Nevada, one of about a dozen states with a minimum wage higher than the national rate, minimum pay has jumped 60 percent since 2006, from $5.15 to $8.25 for uninsured hourly workers. (For hourly workers with employer-sponsored health insurance, the state's rate equals the national rate.) The minimum-wage gains far outstrip broader pay trends, which have been flat.

Employers have responded to higher minimum wages in three ways: They've replaced their lowest-skilled workers with technology -- consider self-checkout grocery lines -- and they're making higher-paid workers do more, such as restaurants asking waiters to bus their own tables. They've also gravitated toward more experienced workers. All of those approaches displace teens, Saltsman said.

"If an employer has to pay more, it makes sense to hire someone who requires less training and who can come in and start the job right away," Saltsman said.

Waddoups agreed that the higher minimum wage could be contributing to persistent teen unemployment, but he added that it's not the biggest hurdle to finding work.

In 2001, teen joblessness averaged 14.7 percent nationwide, compared with average joblessness of 4.7 percent for workers of all ages, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That's roughly proportionate to today's spread between 24.2 percent teen joblessness and 9.1 percent overall unemployment, Waddoups noted.

"The teenage unemployment rate is always higher. It's just harder for unskilled workers to get jobs. That's always going to be the case," Waddoups said. "Not only that, but teenagers aren't quite as stable. They haven't figured out what they want out of life. We're going to find that the unemployment rate for teens is higher until they change the way they behave."

But Waddoups and others say a few policy prescriptions could help get teens off of the family room couch and into the work force.

A CALL FOR INTERVENTION

An April report from the Center for Labor Market Studies at Boston's Northeastern University called for "massive new summer jobs intervention" at the federal level, noting that 2010's cut in funding for federal programs that pay state and local agencies to hire teens led to a sharp drop in employment among low-income kids, in particular.

But Saltsman said businesses were willing to hire teens in the past without a government subsidy. Instead, he suggested that lowering the minimum wage and replacing the lost pay through an earned-income tax credit would encourage employers to hire.

Saltsman also suggested a tiered system that would allow employers to pay lower "training" wages to teens.

Several states, including Arizona, Maine and Missouri, have considered training wages, and Illinois and Michigan already set lower minimum pay for teens. Illinois and Michigan still rank in the top 25 for teen joblessness, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, but their rates -- 25.8 percent in Illinois and 28 percent in Michigan -- are substantially lower than Nevada's.

Saltsman said current training wage laws come with caveats and strings that make them less effective than they could be. In Illinois, for example, the training wage is good for only 90 days.

Asked if reducing or eliminating the minimum wage would create a race to the bottom in pay, Saltsman said anecdotal evidence shows it wouldn't.

The vast majority of workers already earn more than the minimum, he said, noting that McDonald's offered $8.50 an hour when it hired 50,000 workers nationwide on April 19.

The best fix for the problem, Waddoups said, is to boost demand for labor. Improved jobs activity could come from either tax credits for small businesses that hire teens or direct government spending on jobs created by public programs.

Either way, Waddoups hopes for answers, not just as a labor economist, but as a dad. His 18-year-old son is looking for something to do before he heads off to New York University in the fall.

"I just hope we can find a way to solve the problem so my son can get a job," he said.

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4512.

TOUGH FOR TEENS

It's tougher than ever out there for teens seeking work. Here are a few job-hunting tips from employment experts and economists:

• Make your job hunt No. 1. Looking for work should be your top priority from the moment you get out of bed every morning, said Amanda Richardson, senior vice president of product and marketing for SnagAJob, a job-search website specializing in hourly jobs. Give your job hunt structure by sending out a certain number of applications each day and spending a specific number of hours researching job prospects. The more applications you submit, the likelier you are to land an interview.

• Focus on likely targets. It's summertime, so people are traveling and eating out more. That means travel centers, convenience stores and restaurants need more help. Also, scour streets and strip malls for store openings. A new shop may hire 100 or more workers at a time. Richardson noted that discount chain Dollar General is opening 625 stores nationally, including several stores in Las Vegas. Other businesses looking for local hourly workers through SnagAJob include Vons grocery stores, Ulta Beauty cosmetics stores and restaurants Joe's Crab Shack and Wendy's.

Bill Anderson, chief economist with the state Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation, said industries that hired the most Nevada teens in 2010 included retail, construction, hotels and motels and food services. Other industries don't hire as many teens, but they do offer relatively big paychecks to younger hires: Mining paid its teen hires an average of more than $1,200 a week, while the utilities sector paid $795 a week.

• Be flexible. Employers always consider job candidates who say they're willing to take on shorter hours, unpopular shifts or extra duties, Richardson said. Let hiring managers know you can be accommodating.

• Count all of your experience. Even if you've never had a paying job, you can still highlight volunteering with your church, a nonprofit or school clubs and government. Write a résumé detailing your duties with those groups.

• Work for free. If paying jobs aren't coming your way, think about volunteering with a nonprofit or accepting an unpaid internship with a business. Anything that nets you some experience is better than sitting at home, said Michael Saltsman, a research fellow with the Employment Policies Institute in Washington, D.C.

Plus, taking a position without pay has another key benefit: Jeff Waddoups, a professor of economics with the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, said studies show that people who get their first jobs during a recession start so low on the pay scale that their earnings remain depressed throughout their careers. "It's basically a permanent scar to graduate into a recession," he said.

Waiting until times are better to take a paying job could mean increased wages later.