CEO quadriplegic on overcoming spinal injury: ‘I can’t dance anymore, but I can sing’

Scott Frost’s first business venture was anything but legal.

“When I was growing up, in the back of comic books, they had a page that sold firecrackers, and you could put your cash in and mail off for firecrackers,” said the 57-year-old Reno native. “Ever since I was a little kid I was always figuring out ways to come up with something to sell and pitch.”

A 12-year-old Frost was running a side hustle at school, selling firecrackers to students, making a profit by marking up his product like a seasoned professional. Of course, he was caught, the local fire department was notified, followed by a stern talking to by his father.

But Frost, now the chief executive officer of Titan Brands Hospitality Group, which runs a number of restaurants and bars in Las Vegas, including Hussong’s Mexican Cantina and Slice of Vegas Pizza Kitchen & Bar and establishments in Arizona and New York, was already sold on selling at a young age.

“It’s known as the ‘art of woo.’ This ability to woo people and the innate desire to get people to like you. A salesperson isn’t a salesperson unless they can influence people’s decisions. And I’ve always felt that selling things you believe in helps, and I’ve never sold anything I didn’t believe in.”

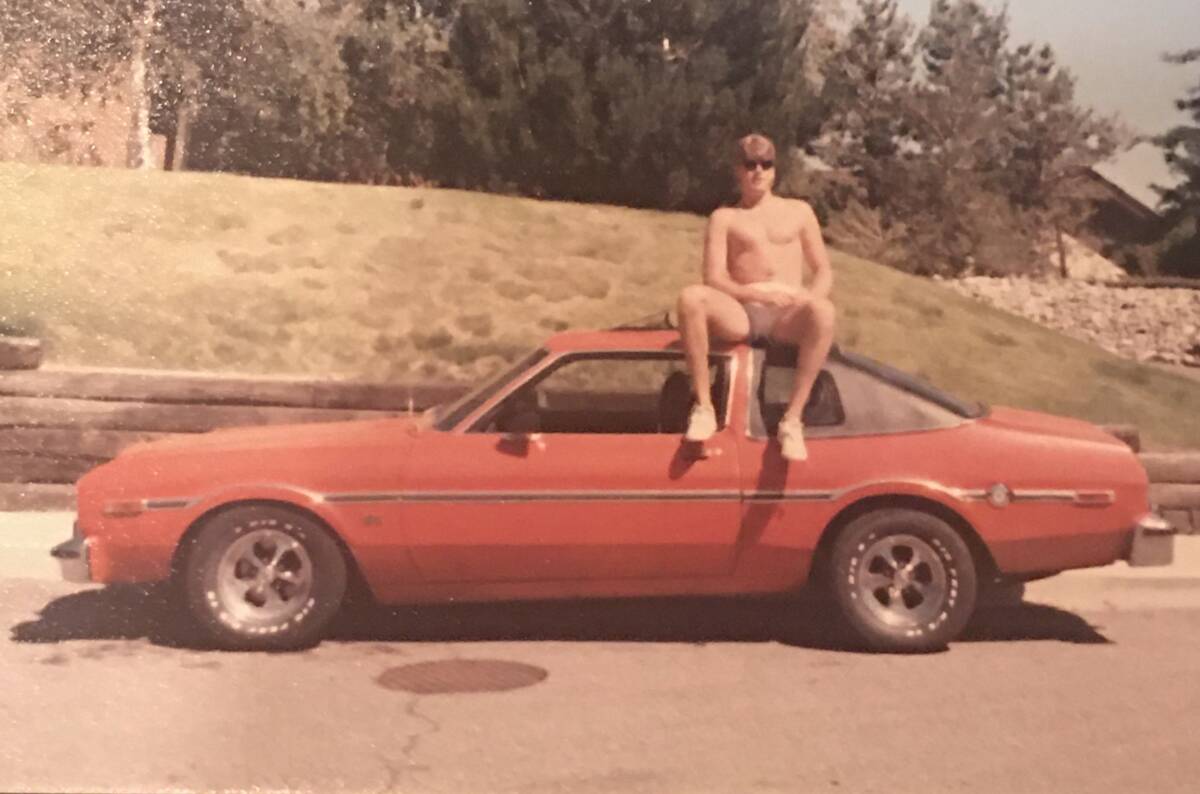

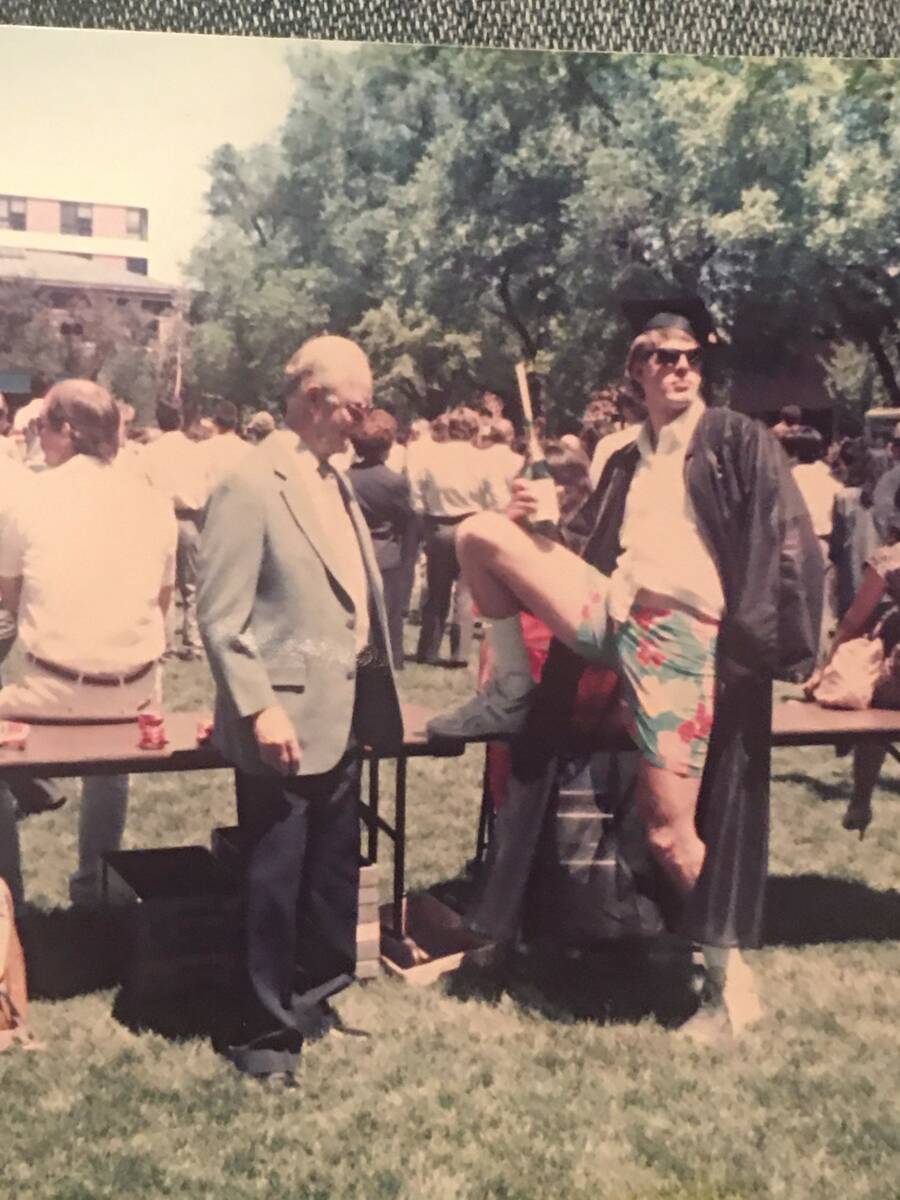

After graduating from high school in 1984, Frost headed to the University of Nevada, Reno where he majored in business with a concentration in marketing and soon Frost was working in the burgeoning telecommunications industry during the initial dot-com boom.

He was wheeling and dealing, working with and against lobbyists on IPOs and multimillion-dollar contracts, and found himself as the vice president of sales and marketing for Smart City Networks up until January 2001, working on some of the first machinations of what would become modern streaming and online gambling.

Frost was on the cusp of a groundbreaking deal, but a generational black swan was about to hit. It was the early morning of September 11, 2001, and Frost was in the lobby of the Holiday Inn at the Newark Airport in New Jersey.

“The demo I was going to give never happened, the meeting never happened, we never got a dime, everything was just frozen, it was the nuclear winter, the economy just froze.”

Frost made his way back to Las Vegas, sullen but not undeterred. He launched his own company, Desert Frost Adventures in 2002, then became the general manager for VegasHotSpots.com, starting his career in hosting and hospitality, working in the early days of the Las Vegas club and nightlife scene as well as consulting for tribal casinos. Frost was on the verge of a huge leasing deal in 2009, turning the old Chocolate Swan at the Mandalay Bay into what would eventually become Hussong’s Cantina. However, everything changed one fateful day in May 2009.

The day everything changed

It was Mother’s Day and Frost was on a dirt bike out in Henderson with a friend and found himself coming up to a rain retention basin. Frost rode up and his tire went over the edge. He was thrown over the handlebars of his bike right onto the crown of his neck. He knew right away, and told his friend: “He asked me if I was OK and I just said, ‘I’ve broken my neck. It’s serious.’”

Frost said the first emotion that came to him was anger.

“I was angry because I knew what I had done to myself. I knew I was paralyzed. I knew it was a severe neck injury, and I knew it was a spinal injury.”

He still remembers the sensation, the inability to move, one he said he will never forget.

“I was receiving no feedback from my body, and they call it proprioception, when you’re able to close your eyes and reach for something, you can feel it when you grab it and you are aware of where you legs are and your arms are. And so suddenly, your body is not getting any feedback, so when you close your eyes, it goes back to your earliest memory, which is in the womb. It feels like your arms are crossed and your knees are drawn up and you are floating in warm water.”

At that point, Frost could barely breath, and asked his friend to call his ex-wife at the time so he could say goodbye to his two kids, thinking he was dying.

“And I was sobbing and I was telling them that I loved them and to take care of each other and their mom.”

By that time a police officer had shown up, and was trying to keep Frost talking so he wouldn’t fall unconscious, so he stayed on the phone, and then Frost prayed, trying to find something to grasp hold of during the most critical of times.

“I said, ‘God, if you’re going to take me, make it quick and make it painless.’ And then this sense of peace and calm just washed over me, like every mortal worry and every mortal pain was just suddenly lifted from me and it just felt amazing. And my last conscious thought was, ‘I wonder what this is going to be like.’”

The long road out of the dark

Luckily, Frost did not die that day, and was instead airlifted to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada. He said his recovery process started instantaneously and he told himself that he was going to overcome this obstacle and fuel himself with positive thoughts.

He spent four days in the intensive care unit which he doesn’t remember, and then found himself staring at the most daunting challenge of his life.

“I remember waking up, I had surgery and it was nine days after that and I’m stable and the doctors were like ‘OK, you’re good to go.’ And I was like, ‘Good to go where?’”

By fortune and luck, he ended up at Desert Canyon Rehabilitation Hospital in the southeast part of the Las Vegas Valley. Right from the get go, Frost, who was 42 at the time, said there was no feeling sorry for himself, and he knew he had to frame this recovery process properly. He instantly started making jokes about his condition, keeping the mood light when people came in, and fostering an environment of happiness and laughter, not regret and sadness.

“It was pure adrenaline. And in a sick way, I enjoyed the challenge. And the first part was simply being able to sit up. When you have a spinal cord injury, if you try to get up, your body will lower its blood pressure which causes you to get nauseous and lose consciousness. So the first thing you have to do in the rehab process is train your parasympathetic nervous system, and the first part of that is just them leaning you up in the bed.”

The tilt table — a large board he was strapped into that could rotate various degrees — was a whole other world of pain and discomfort, Frost said. The first few times he was tilted over he vomited, voided his bowels and passed out. From there it was weeks of repeating the process, over and over, day in and day out, and he credits a song by Las Vegas rock group The Killers called “All These Things That I’ve Done,’ which has the lyrics at the start: “If you can hold on, hold on/I want to stand up, I want to let go” for helping him persevere through an incredibly grueling physical and mental process.

That deal for Hussong’s Cantina at Mandalay Bay that was in the works before his accident — Frost closed it. His girlfriend held his Blackberry up to his mouth as he wheeled and dealed like old times. He got off the phone, looked at everyone in the room with him, and a big grin came across his face.

“I said, “I’m back baby!”

One night in the rehabilitation center, Frost said a saying came to him as he lied awake in a pitch black room, unable to sleep in one of his few moments of doubt. He said the voice was as present as ever, and it had a clear message for him, one that would guide him into the next stage of his life:

“It said to me, ‘All you wanted to do with your life was dance and all I wanted you to do was sing. You can no longer dance, but you can sing.’”

Livin’ life in a chair, one day at a time

Frost said he has good days and bad days. He spends most of his waking hours in a wheelchair, but can stand and walk on his own if his body lets him. Mostly he has to use a walker. He has varying degrees of mobility in both hands, and still has to rely on the help of others to get him through the day.

But he is not a victim, nor does he pity himself. Frost said the accident was actually the best thing that has ever happened to him. He’s done public speaking, written a book about his experience called “Livin’ on a Chair: Lessons of Love and Faith after Breaking My Neck” and still runs the very company he founded before his accident.

Frost said he goes back to his memories of rehabilitation from time to time, and one always sticks out. While he was still in the hospital, his daughter said she was going to run out and grab Starbucks. Frost politely declined, but after she left, it hit him, he was never going to drive a car again, and never going to go on a Starbucks run again.

But he realized this was not the way to frame things, to focus on what he couldn’t do. He had to flip the coin and start counting all the things that he could still do, one of them being walking his daughter down the aisle, which he did years later.

“There are some big ones I can’t do, I can’t take a shower by myself, I can’t drive a car, but there are 15 little things that I can still do. And it’s a mindset thing, if you focus on what you can’t do, guess what will happen, you won’t be able to do anything. But if you focus on what you can do, you can keep achieving.”

Frost said he has framed his accident like this — as a positive experience, because that is how he gathers the strength to continue to battle each day.

“It’s given me a challenge, it’s given me that focus, and that purpose. I’ve always struggled to be present, I even struggled after my injury, it was always business, business, business. And this all really put things in perspective, family is the most important thing. And it took me a long time to learn that lesson, sometimes you’re ahead, sometimes you’re behind, that’s just the way it is, but you can’t get caught up in that rat race because you’ll forget what’s truly important.”

Contact Patrick Blennerhassett at pblennerhassett@reviewjournal.com.